Reconsidering GIRLS

A month ago I participated in a blogathon devoted to the new HBO program Girls. The impetus for the blogathon was a series of discussions I was having with some media studies scholars (primarily Kristen Warner and Jennifer Jones) about the hype leading up to the show’s April 15th premiere. The public discourses surrounding the Girls premiere — in commercials created by HBO, interviews with the press, and reviews by critics who received advanced copies of the first three episodes — primarily stuck to the same theme: Girls is an authentic portrait of what it is like to be a twentysomething female today. Had the show simply been promoted as a new quirky portrait of a pirvileged, highly-educated but emotionally immature young woman’s struggles to make it as an artist in New York City, I am not sure our blogathon would have taken place at all. But the show’s generic title, which implies a universality (even as it mocks the maturity of its protagonists), coupled with the ecstatic reviews lauding the program’s authenticity, bumped up against the program’s rather rigid white, heterosexual, upper-class cast in an unpleasant way. Thus, the blogathon was our attempt to ask: do we take a television series to task for claiming to provide an authentic female bildungsroman when its “authenticity” is limited to one vision of female life?

One thing I did not say in my original post about the show, and which I think needs to be said, is that I do not blame Lena Dunham, the show’s creator, head writer, and star, for the way HBO advertised her show or the way television critics made her show, before a single episode ever aired, into a text that “speaks” for all of today’s young women. Dunham did not, for example, ever claim that her show was “FUBU” (for us, by us). That unfortunate statement came from a glowing preview written by television critic Emily Nussbaum. I enjoy Nussbaum’s work, particularly the way she writes about female characters on TV, but this was an absurd thing to write (well, to be fair, she was quoting her colleague). In addition to the problem of appropriating the phrase “for us, by us,” which was first used by Daymond John for his 1992 clothing line, FUBU (made by and for African American clientele), the claim that Girls was written for “us” by “us” implies that the white, heterosexual, upper class experience is generalizable to all women.

I suppose I understand why Nussbaum would include this statement in her review of Girls. Sometimes when I watch a film or television show, a moment rings so true that I wonder, briefly, if the creator has somehow read my diary. Knowing that this is impossible — I burned all of my diaries! — I then wonder if perhaps this truthful moment is something “universal.” That is an exhilarating feeling — that a private, personal experience is actually an experience linking me to a larger group of individuals. Indeed, you can feel Nussbaum’s excitement and her joy as she writes about Girls — the show clearly tapped into something personal and true for her. I too had moments like that when I watched Girls this season. But, I am also aware that I will have many more moments of personal recognition than, say, a white woman who had to pay her own way through college, or an African American woman who is looking at the screen and seeing no black faces, or a lesbian who is thinking “Seriously ladies, this is one of the reasons why I don’t date men.” To call Girls a show “for us, by us” implies that all of those other “us-es” don’t count.

My reactions to the Girls pilot probably seems nitpicky. “Okay fine,” you might be thinking,”so you’re mad about the way the show was promoted. But what about the show itself? Isn’t it important to judge it on its own merits?” Yes, hypothetical, puzzled reader, you are right. Let’s talk about the show itself: in my original post about the pilot, I was critical of the show’s tone. I felt that Girls was playing coy with its politics. It felt like Dunham was adding a “first world problems” hashtag (complete with air quotes) to the pilot, rather than actually grappling with these issues head on. I wrote:

…the show is awash in its own privilege. It winks and nods, but then dismisses it as if to say “I acknowledged this okay? Can we move on to what I want to talk about now?” If you have the critical fortitude to acknowledge privilege, like when Hannah’s friend scoffs at her for whining about having to pay her own bills (reminding her that he has $50,000 in student loans), then you better well deal with it.

I was honestly confused about what, exactly, Lena Dunham was trying to tell us about her character, Hannah Horvath. Are we supposed to genuinely sympathize with her “plight” or are we supposed to view her existential struggle to become the “voice of her generation” (or “a voice of a generation”) as the whiny complaints of a young woman whose biggest dilemma is that her ex-boyfriend from college has finally come out of the closet? Or that her shirtless, douchebag lover doesn’t text her enough? Or that her best friend is dating a man with, to quote Hannah’s diary, “a vagina”? If, according to Jason Mittell, the goal of a pilot is “to educate viewers on what the show is, and inspire us to keep watching,” then I do think Girls failed in one of its primary jobs — to let us know what the series’ tone will be. Is it a serious drama with sympathetic characters (Parenthood) ? A broad comedy in which characters are built for punchlines (Big Bang Theory)? A world filled with unlikable characters who do awful things and it’s funny (Curb Your Enthusiasm)? A world filled with unlikable characters who do awful things and it FREAKS YOU OUT (Sopranos)?

The Girls pilot did not make its tone clear. If you take that ambiguous tone, couple it with the show’s overblown hype and claims to authenticity, and then look at the blinding whiteness of its cast, then that is the best way to explain why I (and so many others) did not react favorably to the pilot. But I feel differently now, which is why I am writing this follow up post. I think the tone of the series became crystal clear partway through episode 2, “Vagina Panic,” when Hannah decides to get tested for STDs. The scene opens with Hannah wearing one of those flimsy hospital gowns that open in the back, a piece of clothing that is engineered to make patients feel humiliated and therefore, pliant. As Hannah lays back on the examination table, feet in stirrups, she begins to ramble. I want to pause for a moment and point out that generally I hate the way movies and television depict the “foot in the stirrups” scenario because it is usually played for drama — “My God, Mrs. Smith, you’re seven months pregnant!” — or for comedy — “My God, Mrs. Smith, I’ve found your car keys!”

Instead, this scene reveals the pelvic exam, that necessary female rite of passage, for what it is — very, very, very uncomfortable. I don’t care how old I get, I will never be comfortable having a doctor slide her gloved hand into an area which is normally pretty selective about who may enter it, insert a cold metal instrument inside of me so as to make that personal opening wider, and then have a perfectly casual conversation about my summer travel plans as she examines my holy of holies like a miner digging for diamonds. The pelvic exam is one of the few scenarios in which a woman must act like she is totally cool with a stranger rummaging around in her vagina, not for the purposes of generating an orgasm, but to figure out if there is anything “wrong with it.” So I found Hannah’s verbal diarrhea in this scene to be completely appropriate (even if the content of her ramblings was not). This was my “universal moment,” in which I saw a genuinely frustrating experience from my own life recreated accurately on screen.

The tone of the series also became clear to me here because Hannah, in her attempt to fill the air with conversation, launches into a ludicrous monologue about AIDS. I will quote it at length because it must be read to be believed:

The thing is that, these days if you are diagnosed with AIDS, it’s actually not a death sentence. There are so many good drugs and people live a long time. Also, if you have AIDS, there’s a lot of stuff people aren’t going to bother you about. Like, for example, no one is going to call you on the phone and say ‘Did you get a job?’ or ‘Did you paid your rent?,’ or ‘Are you taking an HMTL course yet?’ because all they’re going to say is ‘Congratulations on not being dead.’ You know, it’s also a really good excuse to be mad at a guy. It’s not just something dumb like, ‘You didn’t text me back,’ it’s like ‘You gave me AIDS. So deal with that. Forever.’ Maybe I’m actually not scared of AIDS. Maybe I thought I was scared of AIDS, but really what I am is… wanting AIDS.

What the hell, Hannah?

A nice recap of the episode over at Press Play compares this scene to a scene in the pilot episode of My So Called Life (1994) in which Angela Chase (Claire Danes) tells her English teacher, during a discussion of The Diary of Anne Frank, that Anne Frank was “lucky.” Angela’s teacher is horrified by her response: “Is that suppsosed to be funny? How on earth could you make a statement like that?” she asks. Angela, who has been mooning over her first real crush, Jordan Catalano (Jared Leto), suddenly snaps out of her reverie. After her teacher prods her again, Angela begrudgingly clarifies her response: “I don’t know. Because she was trapped for three years in an attic with this guy she really liked?” If you’d like to watch this scene, start at the 3.30 minute mark on the video below:

This scene is the epitome of that oft-used term “First World Problems.” Only a young woman who is well fed, well loved, and generally provided for would look at the plight of a little Jewish girl forced into hiding during the Holocaust and be jealous of her. Angela is so caught in the throes of her own teenage crush that she is only capable of viewing the world in terms of young women who get to be with their crushes and young women who are kept apart from them. Even something as large as the Holocaust becomes invisible in this world view. If my daughter said something like that I would be forced to give her a lengthy lecture on the nature of “real problems” even as I know that I possibly said something similarly awful at age 15. Indeed, this moment appears in the My So Called Life to tell us almost everything we need to know about the series’ protagonist, Angela: she is privileged; she is uncomfortable in her own skin; she misunderstands and is misunderstood by the adults in her life; and most importantly, she is desperately in love (or what she believes to be love) with Jordan Catalano. This is all that matters to Angela Chase and so her skewed (and horrifying) analysis of The Diary of Anne Frank makes perfect sense in this context. The audience is not expected to identify with Angela here (unless she is also a privileged 15-year-old in love, in which case, she might) but to understand that this scene is telling us what we need to know about Angela as we move forward through this series.

In the same way, Hannah’s infuriating rant about AIDS is a wonderful crystallization of her character. Only a young woman with no “real problems” would fantasize about having a really real problem. Hannah feels that having AIDS would somehow be simpler and more desirable than having to find a job or a boyfriend just as Angela can only see the benefits of being hunted down by blood-thirsty Nazis. As I listened to Hannah blather on I wanted to chastise her for saying such obnoxious things. But then her gynecologist did it for me. She looked at Hannah and said, with the utmost sympathy, “You couldn’t pay me to be 24 again.” This moment acknowledged Hannah’s self centeredness, her privilege and her ignorance about her own privilege, and then, very carefully, cut her some slack. Hannah is, after all, 23. And if I learned anything from Blink-182, it is that “nobody likes you when you’re 23”:

In fact, people in their early twenties are really no better than people in their early teens. In many ways they are worse because they are now equipped with college degrees that lead them to believe that they “understand” things about “the world.” A recent roundtable discussion in Slate, called “Girls on Girls,” offered this perspective on Hannah’s age:

Isn’t that funny arrogance and vulnerability the special purview of the 22, 23, and 24 year old? You are confused, on the low end of the work totem pole or still trying to prove yourself (unless you’re Mark Zuckerberg), and yet you also are young. You’re the next thing. You’ve left your parents’ home and are free to reject all the posters and accoutrements and funny habits and small town-ness of their lives.

A 23-year-old is like a very independent, very entitled toddler who can drive a car and is legally allowed to drink. We say and do very, very dumb things when we are in our early twenties, and that seems to be what Girls is about.

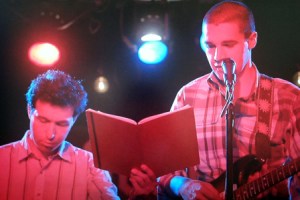

So as this season of Girls draws to a close, I find myself in an uncomfortable situation. On the one hand, I am really enjoying this series. Not every scene or character works (I could completely do without Shoshannah [Zosia Mamet]), but every episode contains at least one scene that I would characterize as “sublime.” And yes, I am using sublime in the Kantian sense of the word, meaning an overwhelming experience that generates awe and respect. I felt this way when Charlie (Christopher Abbott) serenaded his girlfriend, Marnie (Allison Williams), with excerpts from Hannah’s stolen diary that document their relationship from her cynical and judgmental perspective.

When Charlie gets on stage and announces that his next song was wrriten for his girlfriend, Marnie looks pleased (even though we know she does not truly love Charlie). Then, looking Marnie right in the eye, Charlie sings:

What is Marnie thinking

she needs to know what’s out there

how does it feel to date a man with a vagina.

As I watched this slow-moving car crash I was overwhelmed with a confusing mixture of sadness, humiliation, and awkward triumph. To watch Charlie completely abase himself — to throw himself onto his own sensitive-boyfriend-sword — in order to drive home the point that he deserves to be treated with respect, was truly beautiful. Sublime. As Charlie tells Marnie in a follow up episode, he just wants to be treated “like my life is real.” His song did that. This is the kind of scene that makes me happy that I study film and television for a living.

But still, I keep coming back to my original problem with this show — it makes whiteness and it attendant privilege the default setting (and as John Scalzi recently pointed out, “white” is the lowest difficulty setting in the game of life). Why am I picking on Girls for doing what just about every single TV show currently on the air does? Because Girls is written and produced by an extremely smart and talented young woman and if she can’t find a way to make non-white characters, non-straight characters, or non-wealthy characters the default setting, then who is going to do this? Cord Jefferson’s piece in Gawker really nails this issue:

One of the reasons Girls seems to be so adored is that its depiction of upper-middle class, Urban Outfitters ennui reads as more true than most everything before it, as if, at long last, there is finally a team of young people that “gets it.” Many sub-30, post-college men and women look at the show and nod their heads in agreement with every abortion joke, drug reference, and unfortunate sex scene. This stuff is indeed happening in Ivy League pockets throughout the United States, the only difference is it’s happening to black, Latino, and Asian people as well, not just Dunham and her trio of white friends.

There is currently not a single leading character on Girls that couldn’t be played honestly and convincingly by a black actor or a Pakistani actor or a Taiwanese actor. It may come as a surprise to some Americans, but there are women of all races who freeload off their wealthy parents and work in tony art galleries.

Jefferson concludes his piece with this heart-breaking statement:

The guys begging for money look like us. The mad black chicks telling white ladies to stay away from their families look like us. Always a gangster, never a rich kid whose parents are both college professors. After a while, the disparity between our affinity for these shows and their lack of affinity towards us puts reality into stark relief: When we look at Lena Dunham and Jerry Seinfeld, we see people with whom we have a lot in common. When they look at us, they see strangers.

Like the fictional Charlie, the very real Jefferson wants for television to acknowledge that his life is “real.” Like Charlie, he is tired of sleeping over at the white folks’ apartments all the time and hanging out with their friends. He likes them and all, but he wants them to meet some of his other friends. Like Charlie, Jefferson (and every audience member whose world view is routinely hidden from mainstream television) has his own apartment, filled with cleverly constructed shelving units and lofted beds. But like Marnie, white audiences won’t ever know this until we take the time to visit this apartment and look around. So no, Girls is not unique in its erasure of all that is not white, straight and middle to upper-class. But I wish that it were.

For another reconsideration of the series by one of my fellow blogathoners, check out Jennifer Jones’ “GIRLS at the Half.”

May 19, 2012 at 2:49 pm

Great piece, and I agree that the Charlie musical performance was one of the most amazing scenes of TV I’ve seen in a long time.

I’m still convinced that there is a good reason why all the “girls” and their friends are white, as I think the show is “about” whiteness in an indirect way – their experiences are defined by their privilege (and its limits), with the one-level of difficulty up from the straight-white-male default. Had one of the characters been a person of color, even from the same class & educational milieu, it would have highlighted the distinction too much, either by ignoring the racial difference, or calling too much attention to their privilege. It’s a tricky line to toe.

As to the early-twenties comment: is there any age that you don’t look back on 10 years later and say, “man, X-somethings really don’t know shit!”?

May 19, 2012 at 8:49 pm

Thanks for reading and commenting.

I agree that yes, we always look back at an earlier age and marvel at our own stupidity. I marvel at the stupidity of this morning. BUT, there is something very particular about the stupidity of being in your early twenties. I imagine that for folks who went straight into the workforce after high school, that stupid age began at 18. But for those who went to college, it begins at 21 or 22. College kids get to postpone being real adults until graduation and then suddenly they need life skills like ironing a suit and being at work on time. It’s an odd feeling — to have your degree and to know that you are an “adult” but to feel lost and confused. But you know this — you teach college students!

I would love to spend a week being 8 again or 16 again. But as the gynecologist said, you definitely could not pay me to be 24 again. Never.

So I stand by my claim — people in their early twenties suck. They’re useless, navel-gazing alcoholics. But then they grow up to be cynical, bitter thritysomethings who tell twentysomethings how useless they are. It’s the circle of life. Don’t fight it.

May 21, 2012 at 9:17 am

I totally understand where you’re coming from here, as (like you) I see such foolishness unfold on a daily basis.

I wonder, though, what you’d say about those college kids, like me, who worked their tails off during high school (video store clerk!) and throughout their BA and MA (bank teller). Ah, then again, our stories probably aren’t as “interesting” as the useless, navel-gazers’. 😉

May 21, 2012 at 10:23 am

@Kelli I can only speak from my personal experiences, but it has seemed to me that the kids who had to work full time during their undergrad degrees did not experience as much of a shock upon graduation.They were already familiar with the concept of going to a job every single day and answering to a boss. Did you feel less lost after graduation than some of your friends?

I only worked during my summer vacations during my BA and MA so when I took a year off after my MA and took on a full-time job for the year (it was for Habitat for Humanity so it was hardly grueling), it was quite a shock. I hated having to be in an office from 9 to 5. It ensured that I returned to the bubble of graduate school.

May 21, 2012 at 10:42 am

“Did you feel less lost after graduation than some of your friends?” I dunno the answer to that. Most of my friends (predominately guys) worked through college as well, so I doubt it. Once we figured out what we wanted to do with our lives, we were all pretty focused. #Nerds

As someone who has worked since the age of 16 (two jobs while working on the MA) and who paid for her own education, cars, food, cell phones, and rent, I do not identify with, like, or care anything about the characters on this show. Don’t get me wrong: I’m intrigued and am still watching (for now at least), but at this point, I don’t care — if that makes sense.

Perhaps this is also why I wouldn’t label certain scenes “sublime”? 🙂

PS. Geez, I sound like a douche. I don’t mean to sound like a douche.

May 21, 2012 at 10:45 am

I think that the uncomfortable sensations of watching a humiliating pubic break up song are not limited to those who did not have to work during college — maybe you just don’t like the show?

Also, you do not sound like a douche.

May 21, 2012 at 10:56 am

LOL, no of course not! It’s the situations in which these people find themselves that I do not identify with (or care about). And I wasn’t thinking so much of that scene but the masturbation/extortion scene we discussed earlier on Twitter (which, I’m aware, still has little to do with my working through college).

Will politely step away from your lovely blog post now…

May 19, 2012 at 3:54 pm

Nice piece! Not much could get me to go download the three eps I missed, but this did (literally compelling). Shoshanna’s obnoxious, but it’s Marnie who kills me. When I light a cigarette and people say, “You know, smoking is really bad for you” it makes me want to put the cigarette out on their face.

May 19, 2012 at 8:36 pm

I love you Melisser.

May 19, 2012 at 4:33 pm

BTW, I kind of love Jessa.

May 19, 2012 at 8:37 pm

But I do NOT love Jessa.

May 21, 2012 at 8:51 am

I do NOT love Jessa or Shoshanna or Marnie or Hannah. I do, on the other hand, love this post.

May 20, 2012 at 8:28 pm

Again, thanks so much for a second post! Lots to say here. Firstly, I think your opening paragraph hits the nail on the head for the impetus for the FB event as well as the reason ALL THE DISCOURSE that has been written about the show. Media and culture critics might scoff about the level of response now, but it feels those hyperbolic early reviews threw down a gauntlet, especially with a show that’s supposed to be representing this generation that’s so used to plugging in and talking back. Secondly, thanks so much for the inclusion of that comparison to MY SO-CALLED LIFE. I’ve been thinking through my own slightly different comparison to MSCL for my next post, so this just added to that and expanded my vision of Hannah. Thirdly, your description of a 23yo very happily reminded me of this. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cds7lSHawAw Fourthly, I really appreciate your last portion about the issues of whiteness. Still working on what to say about that moving forward, but this gave me more to go on. Lastly but relatedly, I think one of the best things about the blogathon has been the opportunity to stay in conversation and revisit the show through each other. I keep revising and reshaping my own ideas through every post. It feels a little like how the best kind of classroom discussions or online chats should go. Like Hannah & the other show characters, maybe this is part of how we figure things out together as we go along. Thanks again!

May 21, 2012 at 10:25 am

Hi Jennifer

I look forward to to reading your own post on the intersection of GIRLS and MSCL. And I agree, I’ve really enjoyed the blogathon — not just the posts but also having the FB group as a central location for aggregating articles and related posts. I’d love to do this again sometime with another series or a film.

Thanks for reading!

May 21, 2012 at 11:34 am

Great piece. I’ve been enjoying the dialogue around Girls though (ashamed as I am to admit it), I haven’t watched yet. I was intrigued by the discourse surrounding the premiere, but somehow never got to the show. Then, read the blogathon pieces and thought that I knew all I needed to, for now. I may just have to binge watch this week as you’ve really piqued my curiousity.

And you’re right, I’d be thrilled to be 8 or even 16 again. But, 24? Never.

May 21, 2012 at 7:33 pm

Thanks for reading, CB! Despite my different issues with the show (many of which lay outside of the show), I think it’s worth watching. At the very least, Dunham knows how to build up to a great comedic/tragic moment that you see coming, yet don’t see coming in ways that remind me a lot of ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT.

May 21, 2012 at 6:18 pm

[…] was inspired to finally write something by the smart post here by princesscowboy (wait, handles or names? ack! the internet is so weird – anyway) and her observations about […]

August 13, 2013 at 7:59 am

[…] throughout its first two seasons and whose words informed this paper. I also wanted to highlight this post by Amanda Anne Klein, which links out to many of the key pieces and which informed my own […]