highered

BADLANDS: The Film I Always Find a Way to Teach

Whenever I meet new people and they discover that I teach film for a living, they invariably ask me: “So what’s your favorite movie?” I realize that this is polite, small talk kind of question. It’s the kind of question people think that they are supposed to ask me. But to someone who has devoted their livelihood to researching, analyzing, and teaching about moving images, the question is agonizing. Asking me what my favorite movie is is like asking me: “Which of your children do you love the most?” There is simply no way for me to answer this question in a satisfying, honest way. So I usually tap dance around the answer, trying all the while to not sound like a pretentious academic douchebag (which is what I am). “Oh it’s so hard for me to choose!” I say. When the asker looks sufficiently annoyed, I usually submit and say something expected like “Casablanca. Casablanca is my favorite movie” Then they leave me alone.

But the real answer to the question “What is your favorite movie?” is very complex for me. I love different movies for different reasons. I love Double Indemnity (1944, Billy Wilder) for its whipsmart, sexy dialogue. I love The Crowd (1928, King Vidor) for its winsome, bittersweet ending. I love Magnolia (1999, Paul Thomas Anderson) because it was the only movie to figure out the exact kind of role that Tom Cruise should play. I love The Breakfast Club (1985, John Hughes) because I watched it pretty much every Saturday afternoon on TBS when I was 12 and didn’t realize that they weren’t smoking cigarettes during that one scene in the library. I love American Movie for so many reasons but especially because of this scene:

And I love Terence Malick’s debut film (his DEBUT!), Badlands (1973), because it is, for lack of a better word, a perfect movie. Badlands is a movie that I never tire of watching. I get giddy about the opportunity to introduce it to new people. For that reason, I try to put Badlands on my syllabus whenever possible. In fact, this week I screened Badlands for my Film Theory and Criticism students for our unit on film sound. I love teaching this film because, as I mentioned, it’s perfect, and most students have not heard of it. Therefore, after the screening students generally exit the classroom with the same dazed, but happy, expression I had after I watched it for the first time.

So what makes Badlands a “perfect” movie?

Terence Malick’s Script

In the very first scene of the movie we see Holly, a 15-year-old girl (Spacek was 24 when she played the role) with red hair, freckles, and knobby knees. She is playing with her dog on her bed. It is a scene of innocence, of total girlhood joy. But this happy, carefree image contrasts with Holly’s vacant, flat, voice over, which informs us “My mother died of pneumonia when I was just a kid. My father kept their wedding cake in the freezer for ten whole years. After the funeral he gave it to the yard man. He tried to act cheerful but he could never be consoled by the little stranger he found in his house.” In four brief lines Holly aptly summarizes her childhood: she was an only child; her father was once a real romantic (he kept his wedding cake in the freezer for 10 years after all) but the untimely death of his wife deadened his heart (he gave the cake to the yard man after his wife’s funeral); Holly and her father are unable to connect emotionally (Holly knows that her father sees her as a “stranger”). Such is the mastery of Malick’s tight script — not a word is wasted.

Malick’s script is also admirable in that he was able to capture the rhythm and the texture of a teenage girl’s stream of consciousness. Holly doesn’t speak like an adult and she doesn’t speak like a child. After Kit kills Holly’s father he instructs her to grab her schoolbooks from her locker so that she won’t fall behind in her studies. Holly’s voice over then tells us “I could of snuck out the back or hid in the boiler room, I suppose, but I sensed that my destiny now lay with Kit, for better or for worse, and it was better to spend a week with one who loved me for what I was than years of loneliness.” If these words were in Holly’s diary they would probably be adorned with hearts over the i’s and little flowers scribbled in the margins.

Holly’s Voice Over/The Stereopticon Scene

There are so many scenes I could point to that illustrate the genius of Sissy Spacek’s line readings in this film, but my favorite is the much-lauded stereopticon scene. After killing Holly’s father the couple flees to the woods and build themselves a Swiss Family Robinson-style tree house (though it is likely that the grandure of this house has been imagined by Holly). In the middle of this segment, Holly sits down to look at some “vistas” in her father’s stereopticon. This is the first time that Holly has mentioned her father since his murder and yet she still does not mention if his death bothers her. As Holly looks at travelogue images of Egypt and sepia-toned lovers, she waxes philosophical, in the self-involved way that only a 15-year-old girl can. As she looks at an image of a soldier kissing a morose young woman she wonders “What’s the man I’ll marry look like? What’s he doin’ right this minute? Is he thinking about me now by some coincidence, even though he doesn’t know me?” As the camera slowly zooms in on this particular image Holly asks, the excitement barely rising in her quiet voice “Does it show in his face?”” The non-diegetic music becomes more intense as the scene progresses. Holly is coming to an epiphany. She is just some girl, born in Texas, “with only so many years to live.” She is aware that her life is structured by a series of accidents (her mother’s death), and yet, that life is also fated (“What’s the man I’ll marry look like?”). This voice over indicates that Holly is able to see her role in the larger web of humanity, and yet, this same girl watches as her boyfriend shoots her father and random unfortunates who happen to cross their path. It is infuriating and chilling. In fact, every time I watch this scene I get chills.

Kit/ Martin Sheen

I can’t say that I know much about Martin Sheen’s body of work, other than his roles in Apocalypse Now (1979, Francis Ford Coppola) and Wall Street (1987, Oliver Stone). I do know, however, that Martin Sheen frequently mentioned that Badlands was his best work. And I’ll take his word for it. Sheen is amazing in this role. He plays Kit as a man in limbo, a study in contradictions. He lectures Holly about the dangers of littering (“Everybody did that, the whole town’d be a mess”) but shoots her father without comment. He fancies himself a man of ideas, but when given the opportunity to speak, he has nothing to say. Kit wants to be a rebel, like his idol James Dean, but he speaks in platitudes.

Kit is constantly wavering between two poles. Sheen could have therefore played Kit as a bipolar monster — a man who shifts from one personality to the next. But instead, he makes Kit’s duality into an integrated whole. He plays Kit as a man who does not know who he is or what he should do; he only knows that he must fully commit himself to whatever choice he makes. For example, after Kit has been arrested he is allowed to speak with Holly briefly. Kit boasts “I’ll say this though, that guy with the deaf maid? He’s just lucky he’s not dead, too.” Then, in the same breath he tells Holly “Course, uh, too bad about your dad…We’re gonna have to sit down and talk about that sometime.” These moments are almost comical. Indeed, my students often laughed at Kit’s antics, even when he was shooting people.

The Music

I am incapable of talking about film music in a useful way. I can only ever use vague words like “haunting” or “tense” to describe a score. But there is something … haunting … about the non-diegetic tracks used in Badlands, such as the angelic, choral music that plays as Holly’s childhood home is consumed by fire:

So I suppose the next time someone asks me what my favorite movie is, I should just say “Badlands.” It wouldn’t be true, of course. As I mentioned, I could never pick just one. But it’s a movie that represents everything I love about movies: beautiful cinematography, impeccable acting, a tight script. And those chills.

Tweeting at you Live from Console-ing Passions!: The Politics of the Backchannel

Note: all tweets quoted in this post are mine, unless otherwise indicated.

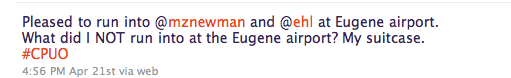

I just returned from 4 days in Eugene, Oregon for Console-ing Passions 2010, a conference on television, audio, video, new media and feminism. Console-ing Passions (aka, CP) is consistently one of my favorite conferences and dfter 3 ½ months of maternity leave it was invigorating to have some personal and professional time (not to mention 3 great nights of sleep). The panels I attended—from discussions of “post-racial” television to vomiting in Mad Men—were smart and thought provoking. Also smart and thought provoking? The “backchannel” of tweets that documented, augmented and critiqued the various papers over the conference’s three days.

There was much grumbling (at least on Twitter) about SCMS’s lack of Wi-Fi this year and the consequent inability of attendees to tweet at the conference. So there was much rejoicing when CP’s gracious host, the University of Oregon, made sure that all conference participants were given access to the university’s Wi-Fi. The CP home page also provided a hashtag for the conference–#cpuo—which enabled the backchannel to open up as early as Wednesday, the day before the conference started. Various twitterati announced their arrival times and chronicled their (positive and negative) travel experiences.

I live-tweeted through most of the panels I attended—first on my laptop and then, when that battery died, I moved to typing one handed on my old school I-Touch (hence, my many typos, and poor use of punctuation).

Through the first day of tweeting I was delighted to see so many folks who weren’t at CP joining in on in the online conversation. Despite this atmosphere of intellectual exchange, I discovered, over the course of the conference, that many folks at the conference were uncomfortable, and even annoyed, with the Twitter backchannel. Indeed, I believe that the presence of this back channel—and the various responses it provoked in conference attendees—is one of the most interesting discussions to come out of this year’s Console-ing Passions. Here is what people were saying—both for and against—this year’s very rich (and very controversial) backchannel:

The Uses of the Backchannel

1. For those who cannot attend

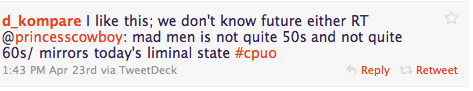

I was unable to attend this year’s SCMS in Los Angeles but was grateful for the few tweets that were broadcasted over the course of the 5-day conference (I was also an avid reader of Antenna Blog‘s informative daily recaps). I was pleased to see regular film/tv/media tweeters like d_kompare and fymaxwell engaging in the discussions on the backchannel. Sometimes their comments were merely appreciative while others raised useful questions:

2. It enriches the dialogue by multiplying voices

In an ideal world, the comments from absent twitterers, such as the one displayed above, would then be posed to panelists by during the Q & A session. In this way, scholars who are unable to attend the conference can still be a part of the conference dialogue. In fact, some tweeters at CP were able to “virtually” attend more than one panel at a time–by reading the tweets being broadcasted from the various rooms.

3. Extend and invigorate Q & A

Panel Q & A sessions are always rushed, even when panelists keep their papers within the proscribed time limits. What I enjoyed most about the CP backchannel was that the audience was able to have an on-going discussion of the papers, before, during and after the Q & A session.

I also felt that in several instances the tweets helped the twitter community to formulate better questions for panelists. For example, during Thursday’s Mad Men panel there was a lot of talk on the back channel about the papers were not satisfactorially addressing depictions of race and class depictions on the show. These sentiments were bandied about by tweeters and this culminated in one person standing up to ask that very question during the Q & A. This question—and the intelligent responses it provoked from the panelists—ended up being the most interesting (at least for me) part of the Q & A.

4. Digital Archive

Finally, the backchannel offers a flawed/funny/smart/critical archive of the entire conference—from the arrival of panelists in Eugene to the (tipsy) tweets coming out of Friday night’s reception.

Think of it as the most detailed conference recap you can find.

The Misuses of the Backchannel

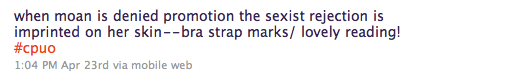

1. The Complex is Simplified

As all academics know, the less space you are given to make your point (as in a conference proposal), the more simplified your argument becomes. The 140 character limit of Twitter has the potential to transform a subtle, elegant argument into something that is too simple, too binary.

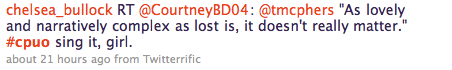

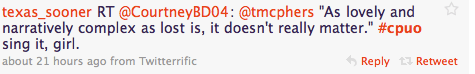

And without the context of the rest of the paper, simplified, isolated tweets can lead to the complete misrepresentation of a speaker’s argument. For example, Tara McPherson’s plenary paper “Remaking the Scholarly Imagination” was subject to a series of engaged and enthusiastic tweets (I am disappointed that I missed this plenary). However, one of McPherson’s statements, made during the Q & A, was retweeted by numerous people:

Some tweeters championed this bold statement while others were troubled. Regardless, McPherson felt that her comment was taken out of context and that she was being somewhat misrepresented on Twitter:

This conversation culminated in a blog post by TV scholar Jason Mittell (who was not able to attend this year’s conference) in defense of Lost studies. McPherson also commented on Mittell’s post, which lead to an interesting conversation about what happens when statements become part of the public discourse. You can read their very interesting exchange in the comments section of Mittell’s blog.

2. Negativity

Being misrepresented on Twitter is one thing—indeed, it is par for the course in academia. But being trashed is quite another. I have yet to read the entire #cpuo backchannel, but so far I have not encountered much negativity towards the various panels or panelists. I did encounter moments when a twitterer disagreed with a panelist or had some big questions to ask but I think this kind of tweeting is both healthy and necessary. It only becomes problematic when those disagreements and questions remain in the realm of the virtual, rather than the actual. Be critical and raise questions on the backchannel, but if you do, make sure you raise your hand when the Q & A begins. Otherwise, these comments can become the equivalent of the anonymous Amazon.com book review—difficult to trust because there is nothing at stake in the criticism.

Given how much people enjoy the twitter backchannel (myself included) I believe that it’s presence at conferences is only going to become stronger. Having said that, I do think the twitterverse and the academic community need to work together to come up with a series of protocols governing the use of the backchannel at conferences. Perhaps panelists can request that their work not be tweeted or maybe twitterers should identify themselves at the beginning of a panel so that speakers know when and if their work is being discussed online. But the issue must be addressed to ensure that everyone who presents their work at a conference feels comfortable with the arrangement.

But now I’d like to hear your thoughts. Please comment below.

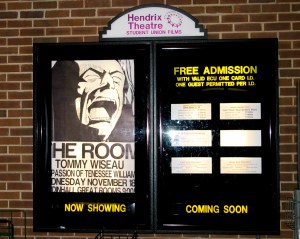

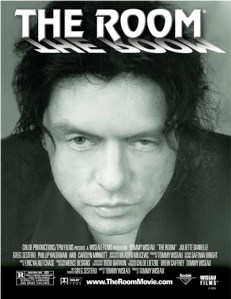

Screening Tommy Wiseau’s THE ROOM

As discussed in previous posts, I am teaching “Topics in Film Aesthetics” this semester, with a focus on what is known as “trash cinema.” For those unfamiliar with this term, trash cinema refers to films thathave been relegated to the borders of the mainstream because of their small budgets, inept style, offensive subject matter, and/or shocking political perspectives. All semester long my students have watched marginalized films like The Sex Perils of Paulette (1965, Doris Wishman) and Sins of the Fleshapoids (1965, Mike Kuchar), interrogating and debating their style, subject matter, and ideology. Why are these films considered to be “bad” movies and what do we have to gain by studying them?

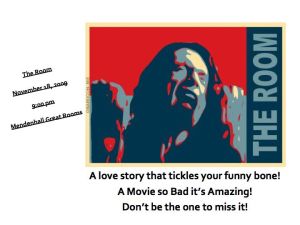

We also spent much of the semester discussing how and why certain films (The Rocky Horror Picture Show [1975, Jim Sharman], El Topo [1970, Alejandro Jodorowsky]) were able to achieve cult status as midnight movies and what drives audiences to perform elaborate rituals at film screenings. In keeping with these discussions, the class project was to host, promote and run a screening of a contemporary cult film, the notoriously awful The Room (2003, Tommy Wiseau). Since my students had read so much about midnight movies and the great lengths that theater exhibitors would go to draw in potential ticket buyers (known as “ballyhoo”), my hope was that the class would put some of those lessons into practice.

Early in the semester the class broke themselves up into working groups: promotions, advertising, booking the venue, etc. The advertising group was responsible for designing flyers, posters and ad copy for the promotions group to implement. Although money is tight in my department, my chair was kind enough to allow us limitless copies for our flyers and $50 for two large posters (I limited my role in this project to obtaining funds for the $100 screening license and for adveritising materials):

Once posters and flyers were created, it was time for the promotions group to start spreading the word. In addition to putting flyers up around campus and doing a word of mouth campaign, they started up a Facebook group for the event and convinced a writer for the campus newspaper, The East Carolinian, to mention the screening in an article about campus happenings.

Nevertheless, as the night of the screening approached I was a little nervous: I had not seen many flyers up around campus and I was beginning to doubt the class’ enthusiasm for the project. To make matters worse, the screening was held on a rainy night (ECU students are relcutant to do anything unless it’s 70 degrees outside and precipitation free) when District 9 (2009, Neill Blomkamp) was playing for free in the same building as part of the Student Activities Board’s fall film series. Finally, our event was booked in a difficult to locate area of the student union. It therefore made sense when barely 50 seats were taken 10 minutes before the start of the event.

I could tell that my students were also starting to get nervous — part of their grade would be based on how many people they could entice into the theater (after all, a theater exhibitor who couldn’t fill seats would lose his/her business). With a few minutes to spare, audience members began to appear in droves, wet from the rain but ready for a good time. By the time we started the film, we had at least 200 attendees:

Most of the people entering the theater took a bag of props to throw at the screen including: plastic spoons (whenever a framed picture of a spoon appears in the mise en scene), chocolates (during a supposed-to-be-erotic scene involving a box of chocolates), and footballs (several scenes feature the male characters tossing around a football, presumably because this is what Wiseau assumes American men do to bond with each other):

I told the students that in addition to gathering a large crowd they needed to foster a participatory screening environment. A silent audience was simply not acceptable. To encourage participation, audience members were handed a photocopied list of rituals selected by the class:

“SPOON!” – Nearly all the artwork in the film features spoons. When they appear in the shot, yell “Spoon!” and fling yours at the screen.

“DENNY!” – Used to herald the arrival/departure of the tragic kidult. “Hi & Bye” is encouraged.

“SHOOT HER!” – Yelled during Lisa’s couch conversation with her mother. The throbbing neck is the cue. Also acceptable, “QUAID, GET TO THE REACTOR!”

“BECAUSE YOU’RE A WOMAN!” – Useful after any comment made in regards to a female character. Considered a dig at the film’s casual misogyny.

“FOCUS! UNFOCUS!” – Frequent shots slip in and out of focus and it is customary to yell “FOCUS” when it gets blurry. Feel free to yell “UNFOCUS!” during the gratuitous sex scenes.

“FIANCE/FIANCEE” – This term is never uttered, instead Johnny or Lisa refer to one another as their future wife/husband. That is the cue to scream “Fiancé & Fiancée”

“ALCATRAZ” – Yell this during scenes framed with bars & during establishing shots of the famous island prison. Also encouraged, “WELCOME TO THE ROCK!” (Connery-esque only)

“GO! GO! GO! GO!” – Used to cheer on tracking shots of the bridge. Celebrate when it makes it all the way across, voice your disappointment when it doesn’t.

“EVERYWHERE YOU LOOK” (Full House theme) – Sung during establishing shot of the San Francisco homes that look eerily similar.

“MISSION IMPOSSIBLE THEME” – Hummed during the phone tapping scene.

“WHO THE FUCK ARE YOU!” – Yelled when characters appear on screen that are out of place or unknown. (Happens more than you think)

“YOU’RE TEARING ME APART, LISA!” – Johnny channels his inner James Dean near the conclusion of the film. Yell along, louder the better.

While this is only a small list of ways to get involved, feel free to interject your own thoughts throughout the screening or join in with audience members who aren’t seeing the film for the first time. All we ask is for you to be safe and respect those around you. Enjoy!

The evening also opened with a brief introduction to the film and its colorful production history. Our Master of Ceremonies encouraged the audience to participate and demonstrated a few of the rituals for the audience.

These tactics seemed to work because almost as soon as the film began, with its useless, extended establishing shots of San Francisco, the crowd was yelling at the screen. They followed the suggested rituals (with “Because you’re a woman!” and “Denny!” being two crowd favorites) but also lots of ad-libbing.

Note: Not from our screening.

When, for example, Lisa (Juliette Danielle) mixes Johnny (Tommy Wiseau) a cocktail of what appears to be 1/2 scotch and 1/2 vodka, someone behind me declared “I call it…scotchka!” [note: I just discovered that this particular line is already a Room ritual]. And whenever a character commented on how “beautiful” Lisa was, several audience members would yell “LIAR!” In fact, the room was rarely silent; people booed, groaned, clapped and heckled throughout the screening.

Note: Not from our screening.

I was hoping that the students would have come up with some more inventive advertising tactics, especially given the time we spent discussing how classical exploitation films like Mom and Dad (1945, William Beaudine) were advertised and promoted. Ultimately though, the class screening of The Room lived up to my expectations. The crowd was rowdy and interactive and everyone seemed to have a great time. Most importantly, I think my students had a great opportunity to experience firsthand what they had only been able to read about.

Excess, Badtruth and the Extratextual in GLEN OR GLENDA

“Let us not mince words. The marvellous is always beautiful, anything marvellous is beautiful, in fact only the marvellous is beautiful.”

–Surrealist Manifesto (1924)

“Badness appreciation is the most acquired taste, the most refined”

-fan of paracinema (qtd. in Sconce 109)

In “Trashing the Academy: Taste, excess and an emerging politics of cinematic style” (1995), one of the first attempts to theorize cult cinema within the academy, Jeffrey Sconce defines “paracinema” as “less a distinct group of films than a particular reading protocol, a counter-aesthetic turned subcultural sensibility devoted to all manner of cultural detritus. In short, the explicit manifesto of paracinematic culture is to valorize all forms of cinematic ‘trash’, whether such films have been either explicitly rejected or simply ignored by legitimate film culture” (101). In an earlier post I discussed how I would be using precisely these kinds of texts in my Trash Cinema course.

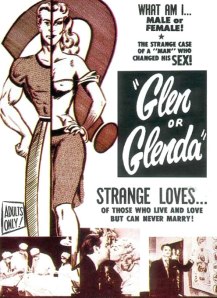

This week my students watched and discussed one prime example of paracinema, Edward D. Wood Jr’s Glen or Glenda? (1953). Glen or Glenda (which has also played under the more sensational title I Changed My Sex) originated as a documentary about the life of one of the first highly publicized transsexuals, Christine Jorgensen, but the film quickly morphed into an odd, often dreamlike self portrait of the director, who was fond of wearing women’s clothing (particularly angora sweaters).

When watching Glen or Glenda? it is vital to know such extratextual details. For example, this knowledge explains Wood’s passionate defense of crossdressing (at a time when men who crossdressed in public were frequently arrested and/or beaten) and his frequent, emphatic claims that the film’s crossdressing protagonist, Glen (played by the director) is NOT a homosexual. At these moments the film becomes Wood’s plea to be understood and embraced by a society bent on rigid gender codification. Indeed, as Sconce points out, paracinematic texts often push the viewer beyond the boundaries of the cinematic frame, demanding that we account for the profilmic.

The moments that pull the viewer out of the fantasy of the text, pointing them to extratextual, are often identified by fans of paracinema as instances of “badtruth”: “As with the [Surrealist concept of the] marvellous, the badtruth as a nodal point of paracinematic style, provides a defamiliarized view of the world by merging the transcendentally weird and the catastrophically awful” (Sconce 112). For example, Bela Lugosi’s role in Glen or Glenda? — a mix between a God figure, a mad scientist, and Glen’s subconscious — is strange and distracting and therefore a primary example of “badtruth.”

The above scene only becomes tolerable (and even pleasurable) when we know that Lugosi was, at this point in his career, a fallen star, desperate for money to support his debilitating morphine addiction. Wood was a huge Lugosi fan and could not believe his luck when Lugosi agreed to star in his film. Despite Wood’s enthusiasm (and one can never doubt Wood’s enthusiasm), he clearly had difficulty fully integrating Lugosi into his crossdressing/sex change film. One of my students even asked “Did Lugosi even know that he was making a film?” These moments of badtruth, when Lugosi plods through nonsensical lines like “Beware of the big green dragon that sits on your doorstep. He eats little boys,” point us to the extratextual, and the extratextual, in turn, contextualizes, even rationalizes, the film’s badtruth. This is the circuitous logic of paracinema and one of its primary pleasures.

The obviously doctored newspaper: a great moment of badtruth in Glen or Glenda?

Unfortunately, the majority of my students did not see it this way. They described the movie as “too long” (the version we watched was just 68 minutes long), “exhausting” and “annoying.” Our discussion of what many cinephiles consider to be the “worst film ever made” naturally led us back to The Room, with my students claiming that the latter was far more enjoyable. As one student put it “Both films were poorly made but at least The Room didn’t preach to the viewer.” Apparently, badtruth on its own is pleasurable, but badtruth mixed with a political agenda is not.

Despite my students’ less than enthusiastic response to Glen or Glenda?, I will continue to screen it in the classroom (it holds a regular spot on my Introduction to Film Studies syllabus). As a fan of paracinema I delight in the way the film constantly pushes me past the frame, to think about its production history, its stars and its now iconic director. But maybe Tim Burton and I are alone on this one? At least I’m in good company…

Scene from Ed Wood (1994, Tim Burton)

Teaching THE ROOM

When I first watched Tommy Wiseau’s The Room (2003), in preparation for my Trash cinema class, I watched it alone. I thoroughly enjoyed this experience but it was not until this week, when I screened it for 21 undergraduates, that I got the full effect of this masterpiece of cinema terrible. I had prepared my students for what they were about to watch: I told them the film had a strong cult following, that it has been dubbed the “Citizen Kane of bad movies,” and that fans had developed their own set of rituals, such as spoon-throwing. But, my students’ enthusiastic, joyous response to the film truly exceeded my expectations.

The moment Tommy Wiseau enters the frame in the film’s first scene and utters the words “Hi Lisa” in his strange, unidentifiable European accent, the room erupted in raucous laughter. And it only built from there. Usually, when I screen a film for students they remain quiet, laughing or gasping when appropriate and occasionally making a stray remark. But when watching The Room my students immediately sensed that it was acceptable to laugh, whoop, and even yell at the screen. When, for example, Lisa (Juliette Danielle) has a prolonged, Cinemax-style sex scene for the 3rd time one of my students exclaimed “But we saw this already, right?” And when a random couple appears in Johnny’s (Tommy Wiseau) and Lisa’s apartment (as characters often do in The Room), another student yelled “Who the hell are they?” When the film was over the students burst into applause, something which has never happened at a screening in my 7 years of teaching film classes to undergraduates.

In our discussion of the film yesterday in class, I asked the students to consider several key questions: Why is The Room considered to be a “bad” film? What codes, conventions, and expectations does it violate and why do these violations provoke laughter (as opposed to boredom or annoyance)? And if this film is so poorly made, then why do audiences gain so much pleasure from watching it?

Here is what we determined:

1. It’s Just Plain Bad

The movie violates almost every rule of storytelling: characters pop in and out of scenes with little explanation, plotlines are addressed and then dropped forever (Lisa’s mother’s cancer, Denny’s [Philip Haldiman] drug problems, etc.), and character dialogue is frequently nonsensical. Wiseau inserts establishing shots of San Francisco into the middle of scenes for no apparent reason and spatial continuity is nonexistent (does Johnny live in an apartment or a house and how do they get up to that roof deck anyway?). These problems are so pervasive that it almost seems as if Wiseau is making these blunders on purpose–but according to reports from his former crew, Wiseau was simply inexperienced.

Wiseau’s senseless dialogue:

One of many scenes that make no sense and do nothing to further the plot:

Who takes wedding photographs one month before the wedding?

Wiseau’s arbitrary use of establishing shots:

The film’s inability to convey the passage of time:

Is it “tomorrow afternoon” already?

2. It’s Camp

The Room is enjoyable precisely because it proposes itself seriously and yet we cannot take the film seriously because it is so over the top. Susan Sontag writes that, “Camp asserts that good taste is not simply good taste; that there exists, indeed, a good taste of bad taste.” My students agreed that in terms of bad taste, The Room is as good as it gets. For example, in one of the film’s many sex scenes, Wiseau employs rose petals, gauzy bedding, bad R & B music, and a sinewy man thrusting away at a woman’s pelvis (I would include this clip but when I uploaded it to YouTube it was determined to be “pornography” and was removed). As my students pointed out, these sex scenes bring together every cliché of the Hollywood sex scene and the effect is overwhelming.

3. It’s Passionate

In Land of a Thousand Balconies: Discoveries and Confessions of a B-Movie Archaeologist (2003), Jack Stevenson argues that a great camp film is “the product of pure passion, on whatever grand or pathetic scale, somehow gone strangely awry… pure camp is created against all odds by the naïve, stubborn director who in the cynical, hardball, bottom line movie business can still foolishly dream he is creating a masterpiece without money, technical sophistication, or (orthodox) talent.” Indeed, The Room is infused with Wiseau’s passion. From its awkward dialogue to its nonsensical plot, the film is the embodiment of this strange, quixotic man. Watching The Room is, in many ways, like the reading the diary of a tortured teenage writer. My students agreed that it was Wiseau’s unadulterated passion and hubris that made the film so engaging to watch, despite its frustrating plot and characterization.

The best example of this passion can be found in the infamous “You’re tearing me apart, Lisa!” scene, a blatant rip off of a similar scene in Rebel without a Cause

But, if The Room is so very personal, if it is Wiseau’s soul up there on the screen, then is it wrong to subject this film to scrutiny on a regular basis? Is mocking this man’s art akin to walking into an art gallery and pointing and laughing at a painting that you think is shit? Or going to the theater and yelling at an actor for being bad at his job?

Fans react to “You’re Tearing Me Apart, Lisa!”:

4. It Makes Us Feel Better About Ourselves

This leads me to the final characteristic of watching The Room: it makes the viewer feel better about him or herself. In his famous study of taste cultures, Distinction (1984), Pierre Bourdieu writes, “Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier. Social subjects, classified by their classifications, distinguish themselves by the distinctions they make, between the beautiful and the ugly, the distinguished and the vulgar, in which their position in the objective classifications is expressed or betrayed.” When we watch The Room and mock it we are essentially saying “I am better than this. I am superior to this.” For example, during the following scene my students howled with laughter–and when we rewatched it during our class discussion they laughed even harder. Why? As one student put it, “This scene is intended to show us that Johnny’s character is a good guy because he is always buying roses for Lisa. But it just FAILS.”

So are we cruel for laughing at Wiseau’s film, for laughing at Wiseau himself? On this point my students were divided. Some said yes, that they felt guilty for laughing because the film was so personal. Others argued that the moment Wiseau made his film and put it in a public theater, he agreed to public ridicule. Personally, I am torn on this issue–but that won’t keep me from watching The Room. And laughing.

The Citizen Kane of Bad Movies

This fall I have the great privilege of teaching a course I have always wanted to teach, “Topics in Film Aesthetics: Trash Cinema and Taste.” Jeffrey Sconce has defined “trash cinema” as “less a distinct group of films than a particular reading protocol, a counter-aesthetic turned subcultural sensibility devoted to all manner of cultural detritus.” Would Sconce agree with the way I am defining trash cinema in my course? I’m not sure. Nevertheless, the term “trash” is a useful way to denote the broad and shifting category of “bad films” and as a method for getting students to discuss film aesthetics. We will watch films that have been maligned for their “bad” acting (Showgirls), “bad” taste (Pink Flamingos), “bad” subjects (Freaks), “bad” politics (El Topo) and just plain “badness” overall (Glen or Glenda?). We will discuss what qualities categorize a film alternately as “bad,” “low brow” or “cult” and how taste cultures and taste publics are established. Finally, we will discuss why certain films are believed to have “cultural capital” and why and how trash cinema rewrites the rules about which films are worth watching.

Every week I will discuss one of these films on this blog, my students’ reactions to them, and whether or not these films offer a useful way for undergraduates to discuss film aesthetics as a political, cultural, economic and social construct. This is also a good excuse for me to talk about some of my favorite films.

The first film the students will watch (during the week of 8/31) is Tommy Wiseau’s The Room (2003). The film has been dubbed “the Citizen Kane of bad films” and has gained an impressive cult following in Los Angeles, where folks line up for midnight screenings. Last year Entertainment Weekly did a wonderful story about it, which is when I first became obsessed with it. The Room even has its own Rocky Horror Picture Show-like rituals.

Which brings me to why I am posting about this now: if anyone out there (are you out there?) is familiar with any of The Room‘s rituals (I know about the spoon throwing and the yelling of “Denny!” whenever that character appears), could you please share them here? My students and I would be most grateful.

More on The Room to come…

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2