The Internets

The Fallacy of Fake News & Both Sides-ism

Note: I was asked to give a sermon at the local Unitarian Universalist Church. The audience was mainly folks over 60, and I think they found this talk useful. I hope you will, too.

I’m a Democrat but I come from a long line of Republicans, so it’s always been difficult to hold different political beliefs from my family. But things have never been so taxing as they have been since the election of Donald Trump. Yes, my family and I disagree on many of Trump’s policies and approaches. But more worrying to me, as a scholar of the media, is how difficult it has become to support claims with evidence that will be accepted. I’ll offer an example to illustrate:

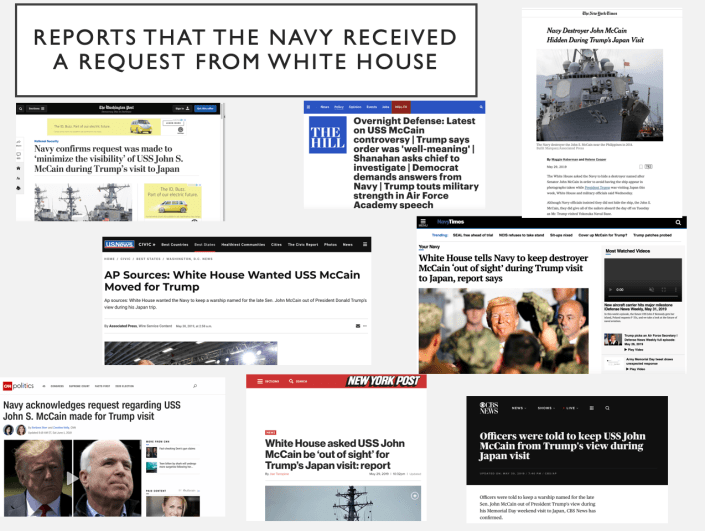

Last weekend my family drove north to central Pennsylvania to see my mother. As with most visits, our conversation invariably turned to politics, specifically, a widely reported story about how the US Navy hung a tarp over a warship docked in Japan, where President Trump was giving a speech last week. The warship in question, the USS John McCain, is named after the father and grandfather of the late Senator John McCain. As I’m sure you all know, Donald Trump maintained a contentious relationship with John McCain, a member of his own party, in both life and death. This particular story—the fact that the warship was covered by a tarp during Trump’s visit—was reported in prominent sources including The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Today, NPR, CNN, NBC News, ABC News, CBS News, and yes, even Fox News. While there is no full consensus on who made this request, all of these news sources cite a statement released by the US Navy’s chief of information, that a request was made by the White House, “to minimize the visibility of USS John S. McCain.”

My mother a staunch Republican, agreed that the story was embarrassing, but then told me that her close friend, Richard, a strong Trump supporter, disputed the veracity of the story.

“Richard said the reason the boat was covered with a tarp is because it was being repaired.”

“And where did he hear that?”

“Fox news,” she replied, but then, before I could say anything, quickly followed up, “But Fox News is where I heard about the story in the first place.”

In other words, both my mom and Richard, staunch republicans who watch Fox News regularly, learned about the covered USS John McCain through the same news source, but came away with very different conclusions. I decided to investigate the root of Richard’s story on Fox News. With a little Googling I found a series of articles on Fox News which mention that the warship’s name was obscured by a tarp and a paint barge, but that this was due to repairs on the ship, not a request from the White House. Faced with dozens of sources reporting that the White House requested the warship be covered and just one source reporting that the ship was simply under repairs, my mother threw up her hands and concluded: how can we ever know the truth?

This question troubled me because my mother reads the local newspaper every morning, and the New York Times on Sundays, and is generally aware of both national and international current events. Of all the people in her educated Boomer demographic, she should know where and how to find reliable and consistent information about the world. So what happened? The first problem my mother faced, and which so many Americans are facing right now, is the misguided belief that there are two sides to every story, and that, at the end of the day, it is simply a matter of one’s opinion. The second problem my mother faced is a deficit in media literacy. While my mom now knows how to minimize a window, print a PDF, and share articles on Facebook, she is less aware of how information functions in today’s media environment. In this respect, my mother is like the great majority of us, not just the Boomers, who consume and share content in an ever-shifting online environment. How does content circulate online and how do we know which sources to trust? This morning, I’d like to unpack these two causes of fake news and the spread of misinformation.

“Both Sides”

One of the most lauded virtues of American society is the idea of free speech and that a plurality of voices is always preferable to the restriction of some in favor of others, hence the appeal to hearing “both sides” of an argument. This feels objectively true and logical, but like all things in life, functions quite differently in different scenarios. Both Sides-ism causes problems when we incorrectly decide that all views on a single topic deserve the same amount of consideration. All political issues elicit a range of opinions, depending on who you’re talking to, but these opinions, these “sides,” do not always carry equal weight. I might be pro-choice because I believe women should have sovereignty over their bodies or because I just hate babies. Both are indeed opinions but one carries far more validity (and morality) than the other. The phenomenon of Both Sides-ism, or false balance, occurs when viewpoints are presented in public discourses as having roughly equal weight, when they objectively do not.

In a New York Times editorial, published in the final delirious months of the 2016 election season, economist Paul Krugman described the phenomenon of Both Sides-ism, this “cult of balance,” as “the almost pathological determination to portray politicians and their programs as being equally good or equally bad, no matter how ludicrous that pretense becomes.”

The consequences of Both Sides-ism are most destructive when all views about personhood are given the same consideration. Take, for example, the recent case, Masterpiece Cakeshop Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission in which a baker refused to make a cake for a same sex wedding, claiming that to do so conflicted with his religious beliefs. The plaintiffs argued this was discrimination while Masterpiece Cakeshop thought the refusal couldn’t be discrimination when it was actually freedom of religion. In this way, Both Sides-ism, this false balance in our discourse, works to legitimate opinions which are not legitimate because equal rights are not up for debate. Another consequence of Both Sides-ism is that, just as it converts opinions into truths, it turns truths into opinions. Because my mother’s friend Richard reported to her that the USS John McCain was covered with a tarp due solely to repairs being made, a story supported by one news source, she felt compelled to give this claim the same weight as the story reported by dozens of news sources, which is that someone in the Trump administration requested that the ship be covered.

We need to be mindful of these slippages and logical fallacies. While there are dozens of opinions for every major political issue, we must always remember that some are more valid than others. And considering some of these opinions, like the idea that same sex marriage is a sin, is damaging. While there is much fake news out there, that does not negate the fact that real reliable news and facts exist. But how can you determine how to find reliable news? That brings me to my second point…

Media Literacy

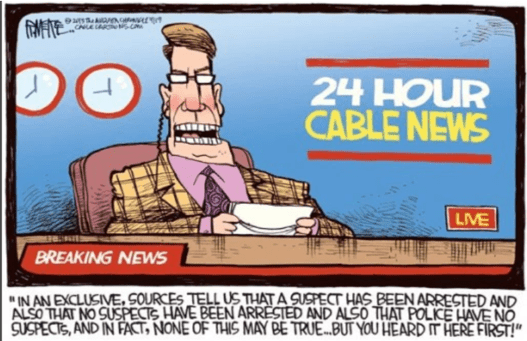

Scholars who study the media and the way it’s content is shaped and deployed have long known that much of the news on cable channels like CNN, Fox, and MSNBC, as well as network and local newscasts, tend to focus on the sensational at the expense of the newsworthy. These scholars have also long known that, in a bid for more eyeballs (and advertising dollars) news headlines, and even news content, can be purposely misleading, incorrect, or yes, even “fake.”

However, in the lead up to, and following, the contentious 2016 U.S. Presidential election, the term “fake news” was deployed more frequently, and in more contexts, than ever before, and not because Americans were suddenly becoming more media literate.[1] The prevalence of the term “fake news” coincided with a rise in conspiracy theories getting traction on social media and then finding their way into public discourse.[2] Take, for example, when White House advisor Kellyanne Conway cited something she called the “Bowling Green Disaster,” an event invented out of whole cloth, as a justification for the Trump administration’s controversial travel ban in February 2017.[3] This increasing inability to discern truth from lies has changed in relation to the technology we have developed for communicating authentic facts. That is, technology is conditioning the way we understand the look and sound of reality and truth. Let’s take a quick trip into our technological past to illustrate what I mean.

Before the global spread of the printing press in the sixteenth century, information about anything outside what you could personally verify was simply not available. When we move forward in time to the circulation of newspapers in the seventeenth century, we are able to learn factually-verifiable things about the world outside our immediate purview, and we are consuming the same facts as our neighbors reading the same newspaper. Again, there is an implicit trust that what we are reading is in, fact, from a reliable source and that this source would have no motivation for misleading us.

The development and deployment of radio and television for the mass distribution of information in the twentieth century likewise carried an implicit trust, inherited from the media that preceded them (namely print newspapers and newsreels that ran before cinemas screenings). Rather than buying a newspaper or venturing out to the movies to watch a newsreel, consumers could enjoy the radio, and the information it provided, without leaving the comfort or the intimacy of their home. Radio also acted a democratizing technology: it gave anyone with a radio common access to events and entertainments that only a tiny minority had been able to enjoy previously.[4] In the 1920s and 1930s, the medium of radio made the world feel like a smaller place when everyone with a radio could listen to the same content being broadcast at the same time.

Just after WWII, when the new medium of television gained a foothold in the American consciousness, it was likewise viewed as a tool for the production of social knowledge, part of a postwar television cultural moment that embraced the medium for its ability to convey realism. The technology of television—its ability to record human behavior and broadcast it live—was linked to a general postwar interest in documenting, analyzing and understanding humanity. By 1960, 90% of American homes had television (compared with 9% in 1950). More and more, Americans were able to consume the same information at the same time, all across the country.

Until the mid-1980s, American television programming was dominated by a small number of broadcast networks: ABC, NBC, CBS and later Fox in 1986. Cable television technology existed as early as the 1940s, a solution to the problem of getting TV signals into mountainous areas. But cable subscriptions steadily rose throughout the 1970s and 1980s in response to new FCC regulations and policies allowed the technology to grow. What’s important for our discussion of fake news is that cable provided access to targeted audiences, rather than the more general demographic targeted by networks. Special interests, homogenous groups, had content made specifically for them.

The development of cable had a massive impact on journalism because, rather than being relegated to the morning or evening news, cable allowed the news to run 24 hours per day. In the 1980s, Ted Turner launched CNN which provided “saturation coverage” of world events like the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 or the first Gulf War. Instantaneous and ongoing coverage of major events as they happen is incredibly useful but also has its drawbacks.

For example, this type of coverage demands an immediate response from politicians, even before they have a chance to inform themselves on developing stories, aka “the CNN effect.” Former Secretary of State James Baker said of the CNN effect “The one thing it does, is to drive policymakers to have a policy position. I would have to articulate it very quickly. You are in real-time mode. You don’t have time to reflect.” CNN’s saturation coverage also increases pressure on cable news to cover an issue first, leading to errors in reporting and even false and misleading information.

In 1996, Rupert Murdoch launched Fox News as a corrective to the liberal bias he argued was present in American media. The new channel relied on personality-driven commentary by conservative talk radio hosts figures like Sean Hannity, Bill O’Reilly, and Glenn Beck, only Fox framed right-wing positions and coverage as “news” and not “opinion.” Thus, the news channel served as decisive blow to the boundary between fact and opinion in journalism. This blurring of fact and opinion, along with the drive for 24 hours of content, has led to an onslaught of information of varying levels of utility.

The development and widespread use of the internet and social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter over the last 20 years has profoundly impacted our relationship with facts and truth. Complex search algorithms, like Google, make information retrieval and organization easier and faster, thereby giving human brains more free time to think and do and make, something engineer. Engineer Vannevar Bush first addressed how creation and publication of research and data was far outpacing the human mind’s ability to organize, locate, and access that information in a timely manner in a 1967 article titled, “Memex Revisited”.[5] He was particularly concerned about a problem that plagues us today: information overload. If attention is a finite commodity and information is increasingly boundless, how can we reconcile the two?

Bush’s essay proposes a solution: a hypothetical microfilm viewing machine, a “memex,” which mimics the way the human brain recalls information and makes connections between different concepts and ideas. While most file storage systems at this time were structured like indexes, with categories, subcategories, and hierarchies of information, Bush’s hypothetical memex was structured by association, working much as the human brain does when searching for an answer. Bush foretells the development of the modern search engine, which is able to process 40,000 queries per second, searching for the exact information a user seeks.

Bush’s essay proposes a solution: a hypothetical microfilm viewing machine, a “memex,” which mimics the way the human brain recalls information and makes connections between different concepts and ideas. While most file storage systems at this time were structured like indexes, with categories, subcategories, and hierarchies of information, Bush’s hypothetical memex was structured by association, working much as the human brain does when searching for an answer. Bush foretells the development of the modern search engine, which is able to process 40,000 queries per second, searching for the exact information a user seeks.

We often think of the ways technology shapes the way we think, but Bush’s essay highlights how the ways we think can also shape the structure of technology. Indeed, complex search algorithms, like Google, make information retrieval and organization easier and faster, thereby giving human brains more free time to think and do and make. Bush described this as the “privilege of forgetting.” But when this perspective bumps up against our current experience of the internet, a memex that exceeds Bush’s wildest dreams, we can also see how the privilege of forgetting might also be one source of the current distrust of the news and the rejection of facts and science.

With that in mind, I made up a hand out outlining basic tips and tricks for figuring out whether or not the news you’re consuming can be trusted, and, more importantly, so you can share these tips and tricks with friends and family. We have to hang onto the truth, and find ways to help those around us hang on, too. Please feel free to share with family and friends (especially your racist uncle): UU Detecting Fake News

Notes

[1] Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. 31, no. 2 (2017): 211-236.

[2] Andy Guess, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler, “Selective Exposure to MisinFormation: Evidence from the Consumption of Fake News During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Campaign,”2018, https://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/fake-news-2016.pdf 2018.

[3] Schmidt, Samantha and Lindsey Bever, “Kellyanne Conway Cites ‘Bowling Green Massacre’ that Never Happened to Defend Travel Ban,” The Washington Post, February 3, 2017.

[4] David Hendy. “Technologies,” The Television History Book, ed. Michelle Hilmes (London, U.K.: BFI, 2003), 5.

[5] Vannevar Bush, “Memex Revisited,” Science is not Enough (New York, New York: William Morrow & Co., 1967).

Tell Us a Story is all new!

As some visitors to this blog may already know, I curate a true story blog over at tellusastoryblog.com. For our first three years of existence, we aimed to publish one new true story every Wednesday (we took summers and holidays off). But we found that model to be unsustainable so we have just switched to a quarterly format, which we are very excited about! We also redesigned the look and functionality of our site.

Tell Us A Story is proud to announce the publication of our first ever quarterly edition of Tell Us A Story, featuring the best work submitted to us over the last few months. Give it a read and a share! Click here to read volume 4, issue 1.

Look for our next issue in Fall 2016!

Plagiarism, Patchwriting and the Race and Gender Hierarchy of Online Idea Theft

Several months ago I published a 2-part guide to the academic job market right here on my blog (for free!!!!!!!!!!), as a way to help other academics explain this bizarre, yearly ritual to family and friends. Indeed, several readers told me that the posts really *did* help them talk to their loved ones about the academic job market (talking about it is the first step!). Yes, I’m working miracles here, folks. And then, this happened:

“A few months ago, as I was sitting down to my morning coffee, several friends – all from very different circles of my life – sent me a link to an article, accompanied by some variation of the question: “Didn’t you already write this?” The article in question had just been published on a popular online publication, one that I read and link to regularly, and has close to 8 million readers.

Usually, when I read something online that’s similar to something I’ve already published on my tiny WordPress blog, I chalk it up to the great intellectual zeitgeist. Because great minds do, usually, think alike, especially when those minds are reading and writing and posting and sharing and tweeting in the same small, specialized online space. I am certain that most of the time, the author in question is not aware of me or my scholarship. It’s a world wide web out there, after all. Why would someone with a successful, paid writing career need to steal content from me, a rinky-dink blogger who gives her writing away for free?

But in this case, the writer in question was familiar with my work. She travels in the same small, specialized online space that I do. She partakes of the same zeitgeist. In fact, she had started following my blog just a few days after I posted the essay that she would later mimic in conceit, tone and even overall structure.

Ethically speaking, idea theft is just as egregious as plagiarism, especially when those ideas are stolen from free sites and appropriated by those who actually make a profit from their online labor.

When pressed on this point, the writer told me that she does read my blog. She even had it listed on her own blog’s (now-defunct) blogroll. But she denied reading my two most recent posts, the posts I accused her of copying. Therefore she refused to link to or cite my blog in her original piece, a piece that generated millions of page views, social media shares, praise and, of course, money, for both her and the publication for which she is a columnist.

So if a writer publishes a piece (and profits from a piece) that is substantially similar to a previously published piece, one which the writer had most certainly heard of, if not read, is this copyright infringement? Has this writer actually done something wrong?”

Well, Christian Exoo and I decided to try to find out. To read our article “Plagiarism, Patchwriting and the Race and Gender Hierarchy of Online Idea Theft” at TruthOut, click HERE.

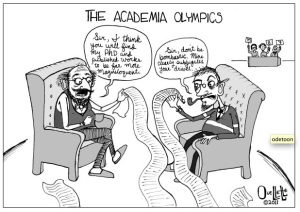

In Defense of Academic Writing

Academic writing has taken quite a bashing since, well, forever, and that’s not entirely undeserved. Academic writing can be pedantic, jargon-y, solipsistic and self-important. There are endless think pieces, editorials and New Yorker cartoons about the impenetrability of academese. In one of those said pieces, “Why Academics Can’t Write,” Michael Billig explains:

Throughout the social sciences, we can find academics parading their big nouns and their noun-stuffed noun-phrases. By giving something an official name, especially a multi-noun name which can be shortened to an acronym, you can present yourself as having discovered something real—something to impress the inspectors from the Research Excellence Framework.

Yes, the implication here is that academics are always trying to make things — a movie, a poem, themselves and their writing — appear more important than they actually are. These pieces also argue that academics dress simple concepts up in big words in order to exclude those who have not had access to the same educational expertise. In “On Writing Well,” Stephen M. Walt argues:

jargon is a way for professional academics to remind ordinary people that they are part of a guild with specialized knowledge that outsiders lack…

This is how we control the perimeters, our critics charge; this is how we guard ourselves from interlopers. But, this explanation seems odd. After all, the point of scholarship — of all those long hours of reading and studying and writing and editing — is to uncover truths, backed by research, and then to educate others. Sometimes we do that in the classroom for our students, of course, but even more significantly, we are supposed to be educating the world with our ideas. That’s especially true of academics (like me) employed by public universities, funded by tax payer dollars. That money, supporting higher education, is to (ideally) allow us to contribute to the world’s knowledge about our specific fields of study.

http://ougaz.wordpress.com/about/

So if knowledge-sharing is the mission of the scholar, why would so many of us consciously want to create an environment of exclusion around our writing? As Steven Pinker asks in “Why Academics Stink at Writing”

Why should a profession that trades in words and dedicates itself to the transmission of knowledge so often turn out prose that is turgid, soggy, wooden, bloated, clumsy, obscure, unpleasant to read, and impossible to understand?

Contrary to popular belief, academics don’t *just* write for other academics (that’s what conference presentations are for!). We write believing that what we’re writing has a point and purpose, that it will educate and edify. I’ve never met an academic who has asked for help with making her essay “more difficult to understand.” Now, of course, some academics do use jargon as subterfuge. Walt continues:

But if your prose is muddy and obscure or your arguments are hedged in every conceivable direction, then readers may not be able to figure out what you’re really saying and you can always dodge criticism by claiming to have been misunderstood…Bad writing thus becomes a form of academic camouflage designed to shield the author from criticism.

Walt, Billig, Pinker and everyone else who has, at one time or another, complained that a passage of academese was needlessly difficult to understand are right to be frustrated. I’ve made the same complaints myself. However, this generalized dismissal of “academese,” of dense, often-jargony prose that is nuanced, reflexive and even self-effacing , is, I’m afraid, just another bullet in the arsenal for those who believe that higher education is populated with up-tight, boring, useless pedants who just talk and write out of some masturbatory infatuation with their own intelligence. The inherent distrust of scholarly language is, at its heart, a dismissal of academia itself.

Now I’ll be the first to agree that higher education is currently crippled by a series of interrelated and devastating problems — the adjunctification and devaluation of teachers, the overproduction of PhDs, tuition hikes, endless assessment bullshit, the inflation of middle-management (aka, the rise of the “ass deans”), MOOCs, racism, sexism, homophobia, ablism, ageism, it’s ALL there people — but academese is the least egregious of these problems, don’t you think? Academese — that slow nuanced ponderous way of seeing the world — we are told, is a symptom of academia’s pretensions. But I think it’s one of our only saving graces.

The work I do is nuanced and specific. It requires hours of reading and thinking before a single word is typed. This work is boring at times — at times even dreadful — but it’s necessary for quality scholarship and sound arguments. Because once you start to research an idea — and I mean really research, beyond the first page of Google search results — you find that the ideas you had, those wonderful, catchy epiphanies that might make for a great headline or tweet, are not nearly as sound as you assumed. And so you go back, armed with the new knowledge you just gleaned, and adjust your original claim. Then you think some more and revise. It is slow work, but it’s necessary work. The fastest work I do is the writing for this blog, which as I see as a space of discovery and intellectual growth. I try not to make grand claims for this blog, mostly for that reason.

The problem then, with academic writing, is that its core — the creation of careful, accurate ideas about the world — are born of research and revision and, most important of all, time. Time is needed. But our world is increasingly regulated by the ethic of the instant. We are losing our patience. We need content that comes quickly and often, content that can be read during a short morning commute or a long dump (sorry for the vulagrity, Ma), content that can be tweeted and retweeted and Tumblred and bit-lyed. And that content is great. It’s filled with interesting and dynamic ideas. But this content cannot replace the deep structures of thought that come from research and revision and time.

Let me show you what I mean by way of example:

Stanley has already taken quite a drubbing for this piece (and deservedly so) so I won’t add to the pile on. But I do want to point out that had this profile been written by someone with a background in race and gender studies, not to mention the history of racial and gendered representation in television, this profile would have turned out very differently. I’m not saying that Stanley needed a PhD to properly write this piece, what I’m saying is: the woman needed to do her research. As Tressie McMillan Cottom explains:

Here’s the thing with using a stereotype to analyze counter hegemonic discourses. If you use the trope to critique race instead of critiquing racism, no matter what you say next the story is about the stereotype. That’s the entire purpose of stereotypes. They are convenient, if lazy, vehicles of communication. The “angry black woman” traffics in a specific history of oppression, violence and erasure just like the “spicy Latina” and “smart Asian”. They are effective because they work. They conjure immediate maps of cognitive interpretation. When you’re pressed for space or time or simply disinclined to engage complexities, stereotypes are hard to resist. They deliver the sensory perception of understanding while obfuscating. That’s their power and, when the stereotype is about you, their peril.

Wanna guess why Cottom’s perspective on this is so nuanced and careful? Because she studies this shit. Imagine that: knowing what you’re talking about before you hit “publish.”

Or how about this recent piece on the “rise” of black British actors in America?

Carter’s profile of black British actors in Hollywood does a great job of repeating everything said by her interview subjects but is completely lacking in an analysis of the complicated and fraught history of black American actors in Hollywood. And that perspective is very, very necessary for an essay claiming to be about “The Rise of the Black British Actor in America.” So what is someone like Carter to do? Well, she could start by changing the title of her essay to “Black British Actors Discuss Working in Hollywood.” Don’t make claims that you can’t fulfill. Because you see, in academia, “The Rise of the Black British Actor in America” would actually be a book-length project. It would require months, if not years, of careful research, writing, and revision. One simply cannot write about hard-working black British actors in Hollywood without mentioning the ridiculous dearth of good Hollywood roles for people of color. As Tambay A. Obsenson rightly points out in his response to the piece:

Unless there’s a genuine collective will to get underneath the surface of it all, instead of just bulletin board-style engagement. There’s so much to unpack here, and if a conversation about the so-called “rise in black British actors in America” is to be had, a rather one-sided, short-sighted Buzzfeed piece doesn’t do much to inspire. It only further progresses previous theories that ultimately cause division within the diaspora.

But the internet has created the scholarship of the pastless present, where a subject’s history can be summed up in the last thinkpiece that was published about it, which was last week. And last week is, of course, ancient history. Quick and dirty analyses of entire decades, entire industries, entire races and genders, are generally easy and even enjoyable to read (simplicity is bliss!), and they often contain (some) good information. But many of them make claims they can’t support. They write checks their asses can’t cash. But you know who CAN cash those checks? Academics. In fact, those are some of the only checks we ever get to cash.

Academese can answer those broad questions, with actual facts and research and entire knowledge trajectories. As Obsensen adds:

But the Buzzfeed piece is so bereft of essential data, that it’s tough to take it entirely seriously. If the attempt is to have a conversation about the central matter that the article seems to want to inform its readers on, it fails. There’s a far more comprehensive discussion to be had here.

A far more comprehensive discussion is exactly what academics have been trained to do. We’re good at it! Indeed, Obsensen has yet to write a full response to the Buzzfeed piece because, wait for it, he has to do his research first: “But a black British invasion, there is not. I will take a look at this further, using actual data, after I complete my research of all roles given to black actors in American productions, over the last 5 years.” Now, look, I’m not shitting all over Carter or anyone else who has ever had to publish on a deadline in order to collect a paycheck. I understand that this is how online publishing often works. And Carter did a great job interviewing her subjects. Its a thorough piece that will certainly influence Buzzfeed readers to go see Selma (2015, Ava DuVernay). But it is not about the rise of the black British actor in America. It is an ad for Selma.

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not calling for an end to short, pithy, generalized articles on the internet. I love those spurts of knowledge, bite-sized bits of knowledge. I may be well-versed in film and media (and really then, only my own small corner of it) but the rest of my understanding of what’s happening in the world of war and vaccines and space travel and Kim Kardashian comes from what I can read in 5 minute intervals while waiting for the pharmacist to fill my prescription. My working mom brain, frankly, can’t handle too much more than that. And that is how it should be; none among us can be experts in everything, or even a few things.

But here’s what I’m saying: we need to recognize that there is a difference between a 100,000 word academic book and a 1500 word thinkpiece. They have different purposes and functions and audiences. We need to understand the conditions under which claims can be made and what facts are necessary before assertions can be made. That’s why articles are peer-reviewed and book monographs are carefully vetted before publication. Writers who are not experts can pick up these documents and read them and then…cite them! In academia we call this “scholarship.”

No, academic articles rarely yield snappy titles. They’re hard to summarize. Seriously, the next time you see an academic, corner them and ask them to summarize their latest research project in 140 characters — I dare you. But trust me, people — you don’t want to call for an end to academese. Because without detailed, nuanced, reflexive, overly-cited, and yes, even hedging writing, there can be no progress in thought. There can be no true thinkpieces. Without academese, everything is what the author says it is, an opinion tethered to air, a viral simulacrum of knowledge.

My Diane Rehm Fan Fiction is Live on Word Riot

Sometimes I try to write creative non-fiction. Luckily, the good folks at Word Riot, a site I greatly admire, thought this was acceptable for publication in their December 2014 issue. I’m super honored and would love if you’d read it. It’s about my idol, Diane Rehm.

The link to “Diane” is here.

Mascara Flavored Bitch Tears, or Why I Trolled #InternationalMensDay

Here are some recent news stories about women:

In Afghanistan, a 3-year-old girl was snatched from her front yard, where she was playing with friends, and raped in her neighbor’s garden by an 18-year-old man. The rapist then tried, unsuccessfully, to kill the child. Currently this little girl is in intensive care in Kabul, fighting for her life. But even if this little girl survives this horrifying experience, her parents tell the reporter, she will carry the shame and stigma of being raped for the rest of her life. The parents hope to bring the rapist to court, but as they are poor, they are certain their family will not receive justice. The child’s mother and grandmother have threatened to commit suicide in protest.

In Egypt,Raslan Fadl, a doctor who routinely performs genital mutilation surgery on women, was acquitted of manslaughter charges. Dr. Fadl performed the controversial surgery on 12-year-old Sohair al-Bata’a in June 2013 and she later died from complications stemming from the procedure. According to The Guardian, “No reason was given by the judge, with the verdict being simply scrawled in a court ledger, rather than being announced in the Agga courtroom.”

Washed up rapper, Eminem (nee Marshall Mathers), leaked portions of his new song, “Vegas,” in which he addresses Iggy Izalea (singer and appropriator of racial signifiers) thusly:

“Unless you’re Nicki

grab you by the wrist let’s ski

so what’s it gon be

put that shit away Iggy

You don’t wanna blow that rape whistle on me”

Azalea’s response was, naturally, disgust and a yawn:

This story was followed, finally, by a story on the growing sexual assault allegations against Bill Cosby. Cosby has been plagued by rumors of sexual misconduct for decades. However, a series of recent events, including Cosby’s ill-conceived idea to invite fans to “meme” him and Hannibal Buress’ recent stand up bit about the star, brought the issue back into the national spotlight. As Roxane Gay succinctly notes “There is a popular and precious fantasy that abounds, that women are largely conspiring to take men down with accusations of rape, as if there is some kind of benefit to publicly outing oneself as a rape victim. This fantasy becomes even more elaborate when a famous and/or wealthy man is involved. These women are out to get that man. They want his money. They want attention. It’s easier to indulge this fantasy than it is to face the truth that sometimes, the people we admire and think we know, are capable of terrible things.”

***

I cite these horrific stories happening all over the world, to women of all ages, races, and class backgrounds, because they are all things that happen to women because they are women. These are all crimes in which womens bodies are seen as objects for men to take and use as they wish simply because they can. The little girl in Afghanistan was raped because she has a vagina and because she is too small to defend herself. Cosby’s alleged victims were raped because they have vaginas and because they naive enough to assume that their boss — the humanitarian, the art collector, the seller of pudding pops — would not drug them. And Iggy Izalea, bless her confused little heart, makes a great point: why is it when men disagree with women, their first threat is one of sexual assault? Why doesn’t Eminem write lyrics about how Izalea is profiting off of another culture or that her music sucks? Because those critiques have nothing to do with Izalea’s vagina. If you want to disempower or threaten or traumatize a woman, you have to remind her she is, at the end of the day, nothing more than a vagina that can be invaded, pillaged and emptied into.

But you know this, don’t you, readers? Why am I reminding you of the fragile space women (and especially women of color) occupy in this world, of the delicate tightrope we walk between arousing the respect of our male peers and arousing their desires to violate our vaginas? Because of International Men’s Day.

“There’s an International Mens Day?” you’re asking yourself right now, “What does that entail?” Great question, hypothetical reader. This is from their official website:

“Objectives of International Men’s Day include a focus on men’s and boy’s health, improving gender relations, promoting gender equality, and highlighting positive male role models. It is an occasion for men to celebrate their achievements and contributions, in particular their contributions to community, family, marriage, and child care while highlighting the discrimination against them.”

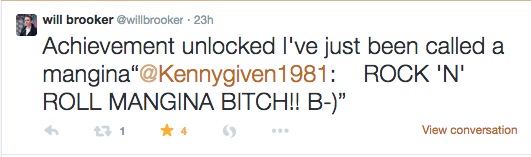

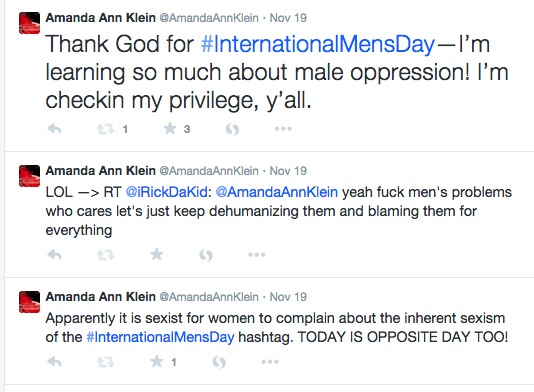

When I opened up my Twitter feed on Wednesday, I noticed the #InternationalMensDay hashtag popping up in my feed now and then, mostly because my friend, Will Brooker, was engaging many of the men using the hashtag in conversations about the meaning of the day and its possible ramifications.

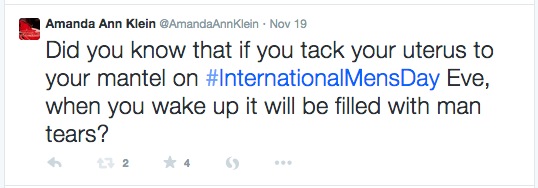

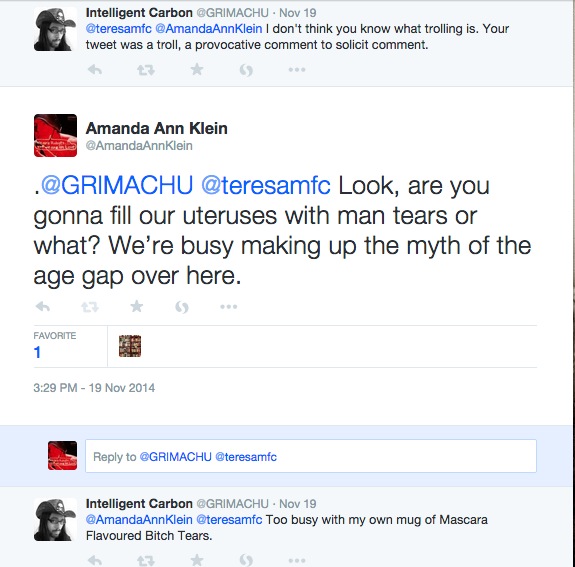

Now, I’m no troll (and neither is Will, by the way). Yes, I like to talk shit and I have been known to bust my friend’s chops for my own amusement (something I’ve written about in the past), but generally, I do not spend my time in real life or on the internet, looking for a fight. But International Mens Day struck me as so ill-conceived, so offensive, that I couldn’t help myself.

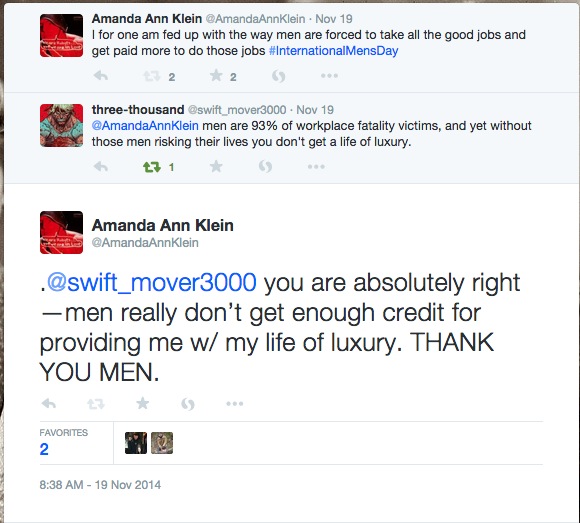

Within minutes I had several irate IMD supporters in my mentions:

I was informed that if you question the need for an International Mens Day, you actually *hate* men:

These men were outraged that I could so callously dismiss the very real problems men had to deal with on a day to day basis:

Yes apparently International Mens Day is needed because all of the feminists are sitting around cackling about the high rates of male suicide, or the fact that more men die on the job than women, or that more men are homeless than women. And since women have their own day on March 8th — and African Americans get the whole month of February! — then why can’t men have their own day, too? After all, men are people, right? Of course they are. But that’s not the point.

As a Huffington Post editorial put it:

“The problem with the IMD idea is that men’s vulnerabilities are not clearly and consistently put into the context of gender inequality and the ongoing oppression of women. For example, a review of homicide data shows that where homicide rates against men are high, violence against women by male partners is also high (and female deaths by homicides more likely to happen). Or, for example, men face particular health problems because we teach boys to be powerful men by suppressing a range of feelings, by engaging in risk-taking behaviors, by teaching them to fight and never back down, by saying that asking for help is for sissies — that is, the values of manhood celebrated in male-dominated societies come with real costs to men ourselves.”

Yes, the problem with IMD is that the real problems faced by men are not the direct result of the fact that they are men. Let me offer a personal example here to explain what I mean. I am a white, upper middle class, high-achieving white woman. According to studies, I am more likely to develop an eating disorder than other women. And eating disorders are very much tied to gender in that women face more pressure to be thin that men do. But does that mean there should be an entire day for white, upper middle class, high-achieving white women in order to bring awareness to the fact that we are more likely to acquire an eating disorder than others? No. Because the point of having a “day” or a “month” devoted to a particular group of people is to shed light on the unique challenges they face and the achievements they’ve made because otherwise society would not take notice of these challenges and achievements. Let me say that again: because otherwise society would not take notice of these challenges and achievements.

We do not need an International White, Upper Middle Class, High-Achieving White Woman Day because I see plenty of recognition of the challenges and achievements of my life; in the representation game, white women fall just behind white men in the amount of representation we get in the news and in popular culture. Likewise, we do not need an International Mens Day because, really, everyday is mens day. Every. Single. Day.

As more and more angry replies began to fill up my Twitter feed, I knew I should abandon ship. I would never convince these men that they do not need a day devoted to men’s issues since “men’s issues,” in our culture, are simply “issues.” But I couldn’t help myself. These men were so aggrieved, so very hurt that I could not see how they were victims, suffering in a world of rampant misandry:

I realize that giving an oppressed group of people their own day or month is a pretty pointless gesture. It could even be argued that these days serve to further marginalize groups by cordoning off their needs, their history, their lives, from the rest of the world. Still, after #gamergate and Time magazine readers voted to ban the word “feminism,” to name two recent public attacks against women, it’s hard for me not to see International Mens Day as an attack on women, and feminists in particular, like a tit for tat.

So yeah, I realize that by trolling the #InternationalMensDay hashtag I did little to promote the cause of feminism or to educate these men about why IMD might be problematic. But I didn’t do it to educate anyone or to promote a cause. I did it, you see, because sometimes in the face of absurdity, our only choice is to cloak ourselves in sarcasm and great big mugs of mascara flavored bitch tears.

Debating the Return of Twin Peaks

You may have heard that Twin Peaks, beloved cult television of my adolescence, is getting a third season on Showtime. That won’t happen until 2016. In the meantime, I’m going to quietly weep about it. Why am I blue? I explain over at Antenna and talk about it with two other fans, Jason Mittell and Dana Och.

Here’s an excerpt:

“I started watching Twin Peaks when ABC aired reruns in the summer of 1990, after some of my friends started discussing this “crazy” show they were watching about a murdered prom queen. During the prom queen’s funeral her stricken father throws himself on top of her coffin, causing it to lurch up and down. The scene goes on and on, then fades to black.

I started watching based on that anecdote alone and was immediately hooked. Twin Peaks was violent, sexual, funny and sad, all at the same time – I was 13 and I kept waiting for some adult to come in the room and tell me to stop watching it. My Twin Peaks fandom felt intimate, and, most importantly, very illicit.

One month before I turned 14, Lynch’s daughter published The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, a paratext meant to fill in key plot holes and offer additional clues about Laura’s murder. But really, it was like an X-rated Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret. The book was far smuttier than the show and my friends and I studied it like the Talmud. That book, coupled with Angelo Badalamenti’s soundtrack, which I played on repeat on my tapedeck, created my first true immersive TV experience.”

Read the whole thing here.

Notes on a Riot

image source: PBS news hour

Like many professors, I live on the same campus where I work. As a result, I’ve watched drunk East Carolina University students urinate and puke on my lawn and toss empty red solo cups into the shrubbery around my home. But one evening I had a more troubling run-in with a college student. It began when I woke to the sound of my dog barking. It took me a minute to orient myself and understand that my dog was barking because someone was knocking on the front door. It was 2 am and my husband was out of town, but I opened the front door anyway. On the stoop was a college-aged woman dressed in a Halloween costume that consisted of a halter top, small tight shorts, and sky-high heels. The woman was sobbing and shivering in the late October air and her thick eye make up was running down her face. She was incoherent and hysterical– I could smell the tequila on her breath — so it took me a while to figure out what she wanted .

She told me that she was visiting a friend for the night and that she had lost her friend…and her cell phone. She had no idea where she was or where to go. I think she came to my door because my porch light has motion detectors and she must have thought it was a sign. As she rambled on and on I could hear my baby crying upstairs. I told the woman to wait on my stoop, that I had to go get my baby and my phone, and that I would call the police to see if they could drive her somewhere. “Nooooooo,” she wailed, “don’t call the police!” I urged her to wait a minute so I could go get my baby and soothe him, but when I returned a few minutes later with my cell phone in hand, she was gone.

image source: http://www.nydailynews.com/

I felt many emotions that night: annoyance at being woken up, panic over how to best get help for the young woman, and later, guilt over my inability to help her. But one emotion that I did not feel that night was fear. I was never threatened by this young woman’s presence on my stoop and I never felt the need to “protect” my property. Why would I? She was a young woman, no more than 19 or 20, and though she was drunk and hysterical, she needed my help. I was reminded of this incident when I heard that Renisha McBride, a young woman of no more than 19 or 20, was shot dead last fall after knocking on Theodore Wafer’s door in the middle of the night while drunk and in need of help. Wafer was recently convicted of second-degree murder and manslaughter (which is a miracle), but that didn’t stop the Associated Press from describing the Wafer verdict thusly:

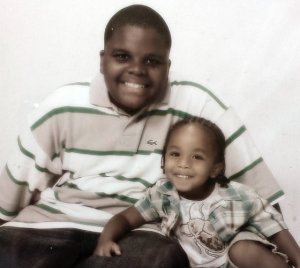

McBride, the victim, a young girl needlessly shot down by a paranoid homeowner, is described as a nameless drunk, even a court ruling establishing her victimhood beyond a shadow of a doubt. Now, just a few days later in Ferguson, Missouri, citizens are actively protesting the death/murder of Michael Brown, another unarmed African American youth shot down for seemingly no reason. If you haven’t heard of Brown yet, here are the basic facts:

1. On Saturday evening Michael Brown, an unarmed African American teenager, was fatally shot by a police officer on a sidewalk in Ferguson, a suburb of St. Louis, Missouri.

2. There are 2 very different accounts of why and how Brown was shot. The police claim that Brown got into their police car and attempted to take an officer’s gun, leading to the chain of events that resulted in Brown fleeing the vehicle and being shot. By contract, witnesses on the scene claim that Brown and his friend, Dorian Johnson, were walking in the middle of the street when the police car pulled up, told the boys to “Get the f*** on the sidewalk” and then hit them with their car door. This then led to a physical altercation that sent both boys running down the sidewalk with the police shooting after them.

3. As a result of Brown’s death/murder the citizens of Ferguson took to the streets, demanding answers, investigations, and the name of the officer who pulled the trigger. Most of these citizens engaged in peaceful protests while others have engaged in “looting” (setting fires, stealing from local businesses, and damaging property).

http://blogs.riverfronttimes.com/

Now America is trying to make sense of the riots/uprisings that have taken hold of Ferguson the last two days and whether the town’s reaction is or is not “justified.” Was Brown a thug who foolishly tried to grab an officer’s gun? Or, was he yet another case of an African American shot because his skin color made him into a threat?

I suppose both theories are plausible, but given how many unarmed, brown-skinned Americans have been killed in *just* the last 2 years — Trayvon Martin (2012), Ramarley Graham (2012), Renisha McBride (2013), Jonathan Ferrell (2013), John Crawford (2014), Eric Garner (2014), Ezell Ford (2 days ago) — my God, I’m not even scratching the surface, there are too many to list — I’m willing to bet that Michael Brown didn’t do anything to *deserve* his death. He was a teenage boy out for a walk with his friend on a Saturday night and his skin color made him into a police target. He was a threat merely by existing.

Given the amount of bodies that are piling up — young, innocent, unarmed bodies — it shouldn’t be surprising that people in Ferguson have taken to the streets demanding justice. And yes, in addition to the peaceful protests and fliers with clearly delineated demands, there has been destruction to property and looting. But there is always destruction in a war zone. War makes people act in uncharacteristic ways. And make no mistake: Ferguson is now a war zone. The media has been blocked from entering the city, the FAA has declared the air space over Ferguson a “no fly zone” for a week “to provide a safe environment for law enforcement activities,” and the police are shooting rubber bullets and tear gas at civilians.

But no matter. The images of masses of brown faces in the streets of Ferguson can and will be brushed aside as “looters” and “f*cking animals.” Michael Brown’s death is already another statistic, another body on the pile of Americans who had the audacity to believe that they would be safe walking down the street or knocking on a door for help.

What is especially soul-crushing is knowing that these events happen over and over and over again in America — the Red Summer of 1919, Watts in 1964, Los Angeles in 1992 — and again and again we look away. We laud the protests of the Arab Spring, awed by the fortitude and bravery of people who risk bodily harm and even death in their demands for a just government, but we have trouble seeing our own protests that way. Justice is a right, not a privilege. Justice is something we are all supposed to be entitled to in this county.

***

When the uprisings in Los Angeles were televised in 1992 I was a freshman in high school. All I knew about Los Angeles is what I had learned from movies like Pretty Woman and Boyz N the Hood –there were rich white people, poor black people with guns, and Julia Roberts pretending to be a prostitute. On my television these “rioters and looters” looked positively crazy, out of control. And when I saw army tanks moving through the streets of Compton I felt a sense of relief.

That’s because a lifetime of American media consumption — mostly in the form of film, television, and nightly newscasts — had conditioned my eyes and my brain to read images of angry African Americans, not as allies in the struggle for a just country, but as threats to my country’s safety. I could pull any number of examples of how and why my brain and eyes were conditioned in this way. I could cite, for example, how every hero and romantic lead in everything I watched was almost always played by a white actor. I could cite how every criminal, rapist, and threat to my white womanhood was almost always played by a black actor. And those army tanks driving through the outskirts of Los Angeles didn’t look like an infringement on freedom to me at the time (and as they do now). They looked like safety because I came of age during the Gulf War, when images of tanks moving through wartorn streets in regions of the world where people who don’t look like me live come to stand for “justice” and “peacemaking.” Images get twisted and flipped and distorted.

bossip.com

The #IfTheyShotMe hashtag, started by Tyler Atkins, illuminates how easily images — particular the cache of selfies uploaded to a Facebook page or Instagram account — can be molded to support whatever narrative you want to spin about someone. The hashtag features two images which could tell two very different stories about an unarmed man after he is shot — a troublemaker or a scholar? a womanizer or a war vet? The hashtag illuminates how those who wish to believe that Michael Brown’s death was simply a tragic consequence of not following rules and provoking the police can easily find images of him flashing “gang signs” or looking tough in a photo, and thus “deserving” his fate. Those who believe he was wrongfully shot down because he, like most African American male teens, looks “suspicious,” can proffer images of Brown in his graduation robes.

Of course, as so many smart folks have already pointed out, it doesn’t really matter that Brown was supposed to go off to college this week, just as it doesn’t matter what a woman was wearing when she was raped. It doesn’t matter whether an unarmed man is a thug or a scholar when he is shot down in the street like a dog. But I like this hashtag because at the very least it is forcing us all to think about the way we’re all (mis)reading the images around us, to our peril.

The same day that the people of Ferguson took to the streets to stand up for Michael Brown and for every other unarmed person killed for being black, comedian and actor Robin Williams died. I was sad to hear this news and even sadder to hear that Williams took his own life, so I went to social media to engage in some good, old fashioned public mourning, the Twitter wake. In addition to the usual sharing of memorable quotes and clips from the actor’s past, people in my feed were also sharing suicide prevention hotline numbers and urging friends to “stay here,” reminding them that they are loved and needed by their friends and families. People asked for greater understanding of mental illness and depression. And some people simply asked that we all try to be kind to each other, that we remember that we’re all human, that we all hurt, and that we are all, ultimately, the same. Folks, now it’s time to send some of that kind energy to the people of Ferguson and to the family and friends of Michael Brown. They’re hurting and they need it.

(Aca) Blogs are Like Assholes…

You’ve heard the joke, right? There are over 152,000,000 blogs on the internet. And in one small corner of the internet are the academic blogs, the aca-blogs. I define “aca-blogs” as blogs written and moderated by an individual (as opposed to a collective) currently involved in academia (whether as a student, instructor or administrator). The content of these blogs vary widely but they are usually at least tangentially related to the blogger’s field of academic study. Most of these bloggers write in a looser, more informal style than they would for a more traditional scholarly publication, like a peer-reviewed journal or a monograph published by a university press (i.e, the kind of documents that — at least at one time — would get you a job or tenure).

Now, I’ve never been an early adopter. I’m a proud member of the “early majority,” the folks who watch and see what happens to the early adopters before taking the plunge. I was late to Facebook (August 2008), Twitter (March 2009), and (aca)blogging (August 2009). I only started blogging in the wake of the medium’s “golden age” (an era which, like all golden ages, varies wildly depending on who you consult). I use the term “golden age” to signal a time when a large portion of the academics I interacted with on social media also had blogs, and posted to them regularly (see my blogroll for a sizable sample of media studies bloggers). Starting a blog was common for people like me — that is, for people who liked talking about popular culture in a looser, more informal way, online, with other fans and academics. And with gifs.

Part of what (I think) my early readers enjoyed about my blog is that I was using my PhD, a degree that (supposedly) gives me the ability to provide nuanced arguments and historical context about the popular culture they were consuming. I like that my online friends (including folks I went to elementary school with, my Mom’s friends, my kids’ friends’ parents) can read my mom’s Oscar predictions or why I think the Jersey Shore cast is a lot like the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and they don’t need to buy a subscription to a journal or be affiliated with a university to do so. That’s important. If we, as Humanities-based scholars, are terrified about the way our discipline is being devalued (literally and metaphorically) then we need to show the public exactly how valuable our work is. How can we say “people need media literacy!” but only if they enroll in my class or pay for a journal subscription? That just supports the erroneous belief that our work is elitist/useless when it’s not. I know this work is valuable and I want everyone to have access to it. I also like the timeliness afforded by this online, open-access platform. I can watch Mildred Pierce the night it airs and have a review published on my personal blog the next day, which is exactly when folks want to read it. If I want to do some detailed research and further thinking about that series, then sure, I’d spend several months on a much longer piece and then send it to a journal or anthology.

Indeed, Karra Shimabukuro, a PhD student who maintains two different blogs, explains her interest in blogging this way:

I like [blogging] because it lets me share my work, and in this day and age perhaps get people to know my work and me. Now that I’m in my PhD program, I try to post stuff pretty regularly, and I always link to Twitter when I do, so get more views. I think it’s important to share my research. I read quite a few blogs, usually when I am looking for something specific though- job market, conference, early career advice type stuff.

In the early days of my blog’s life I posted frequently (several times per week) and my posts were generally short (less than 1000 words). These posts were written quickly, often in response to an episode of television I had just watched or a conversation I had just had with someone on Twitter (or Facebook, or occasionally, real life). My early posts were also interactive. I almost always concluded posts with questions for my readers, invitations to engage with me on the platform I built for just that purpose.

Ben Railton, a professor who blogs at American Studies, told me via email:

For me individually, blogging has been infinitely helpful in developing what I consider a far more public voice and style, one that seeks to engage audiences well outside the academy. Each of my last two books, and my current fourth in manuscript, has moved more and more fully into that voice and style, and so I see the blog as the driving force in much of my writing and work and career.

And collectively, I believe that scholarly blogs emphasize some of the best things about the profession: community, conversation, connection, an openness to evolving thought and response, links between our individual perspectives and knowledges and broader issues, and more.

Looking back at these early posts I’m surprised by the liveliness of the comments section — how people would talk to me and each other in rich and interesting ways. In 2009 my blog felt vibrant, exciting, and integral to my scholarship. A few of of my posts became longer articles or conference talks. Writing posts made me feel like I was part of an intellectual community exchanging ideas back and forth in a productive kind of dialogue.

In hindsight it’s strange to me that I blogged so much in 2009 and 2010 because those years mark one of the most challenging periods of my life — just before the birth of my second child, a beautiful boy who never ever (ever) slept. During the brief snatches of time when my newborn son was asleep, or at least awake and content, I would grab my laptop and compose my thoughts about The Hills or Google+ (LOL, Google+!). I found that, when the muse comes calling, you have to write then, not sooner and not later, or she’ll go away. So I wrote posts in the middle of the night and even while nursing my son. Blogging felt vital to me then, like a muscle that needed stretching. And when the words came, they came in a stream. The sexual connotations here are purposeful — blogging was satisfying to me in the same way sex can be satisfying. And like sex, sometimes when you try to blog, you just can’t get it up: the moment’s not right, the inspiration vanishes.

But things are different in 2014. I’ve had tenure for a year. I just completed a manuscript and turned it in to the press. My son (now 4 and a half) sleeps through the night (almost) every night and I find that I can work while lounging in a hammock next to my 8-year-old daughter as she reads. In other words, I have plenty of time to stretch my blog muscle. Yet, I’m just losing my desire for blogging. It used to be that if I went more than a few weeks without writing a post, I got twitchy, an addict in the midst of withdrawal. But now, my blog’s stagnation engenders no such discomfort. It’s like the day you realize you’re over an old love. Dispassion and neutrality abound.

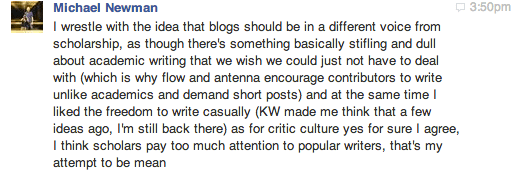

Taking stock of her own blogging hiatus last year, Slaves of Academe writes “As it turns out, walking away from one’s blog was relatively easy, given the surplus of competing screens.” And I suppose that that’s the first reason why I blog less frequently than I did 5 years ago. Back in 2009 it seemed that the internet was quite interested in the proto-scholarship offered up by the academic blog. There was an excitement there of seeing new scholarship take shape right before our eyes. And Michael Newman, a media studies professor writing about this same topic on his own personal (neglected) blog, zigzigger, explains:

People mixed personal and professional. They’d get first-persony and confessional even in efforts at engaging with intellectual concerns. They’d make the blog as much about process as product. No one was editing or reviewing your blog, so it had a raw immediacy missing from more formal writing.

Newman notes the rise of academic blog collectives (like Antenna), a move which has, for better or worse, worked to legitimize the process of academic blogging:

As blogs become more legitimate and serve these more official functions, they seem less appropriate for the more casual, sloppy, first-drafty ponderings that made the format seem vital in the first place.

This has certainly been true for me. I often find myself starting to write a post and then abandoning it for it’s lack of intellectual “rigor.” I second guess my posts more often now, worrying that they might be too frivolous, too self-indulgent, too weird. But of course, that’s what my blog has always been. It just seems like that sort of casual, stream-of-consciousness style writing is less acceptable now among academics. Or maybe everyone is just bored with it.

Justin Horton, an ABD who has been blogging since 2012, has noticed an overall decrease in the numbers of posts coming out of personal blogs. He tells me:

Personal blogs have been diminished by other web spaces (Antenna, etc), but there is still a place for them, and oddly, it seems be occupied by very young scholars (who haven’t gotten their names out there) and senior scholars whose names are widely known and have a built-in audience (I’m think of Bordwell, Steven Shaviro, and so forth).

Years ago it seemed like blogs represented the next wave of academic scholarship: short bursts of freeform thinking published immediately and set in dialogue with other robust online voices. But blogging has not yielded the legitimacy many of us hoped for. While I still put my blog in my tenure file, citing (what I believe to be) its value, I understand that my department’s personnel committee does not view it as a major component of my research, teaching or service (the holy trifecta of academic values), even though it has greatly contributed to all three. So without institutional legitimacy or scholarly engagement, what purpose does the academic blog hold today? Has its moment passed?

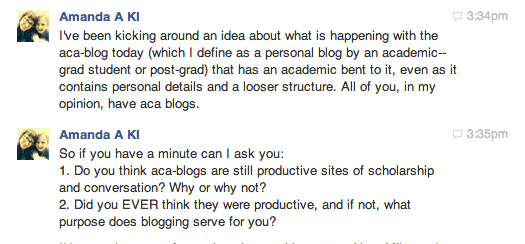

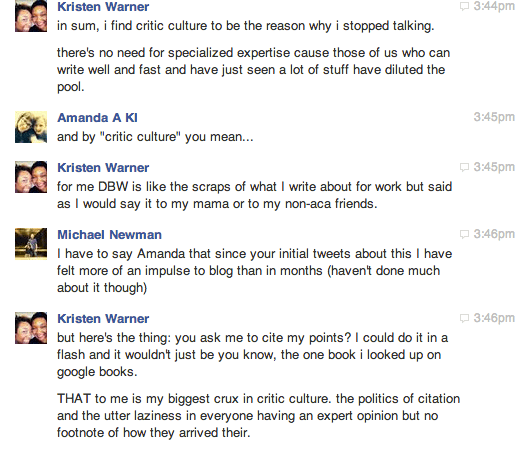

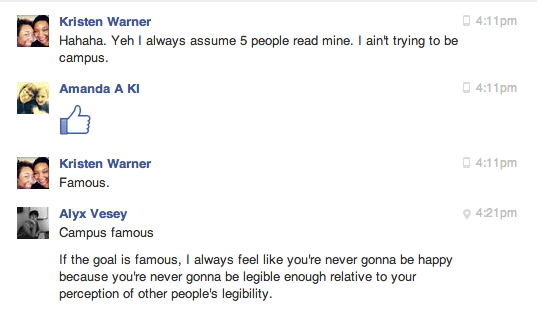

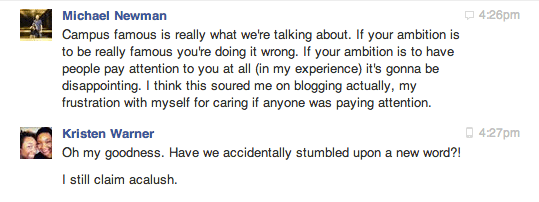

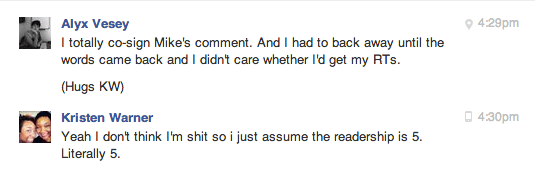

I had a chat, via Facebook message, with three fellow aca-bloggers — the aformentioned Michael Newman, Kristen Warner of Dear Black Woman, and Alyx Vesey, of Feminist Music Geek — to get some answers. I’ve pasted our discussion below:

Kristen started things off, by addressing the rise of the so-called “critic culture”:

Editor’s note: I really really love Google books.

Editors’s note: here is a link to Kristen’s post on Jessica Pare.

Editor’s Note: Alyx is referring to Myles McNutt, of Cultural Learnings (and the AV Club and my heart).

No, the slow disappearance of the personal aca-blog isn’t exactly a crisis — not like the academic job market crisis, or the humanities crisis, or the crisis in higher education. But the downtick in blogging in my field does give me pause because I see real value in the kind of intellectual work performed on blogs. Posts are loose, topical, and invite others to join in. They’re accessible in a way that academic journal articles usually are not. And unlike the think pieces and recaps I most frequently read online (and which I enjoy), personal blog posts are rarely subjected to the rabid feeding frenzy of misogyny, racism and obtuseness that characterizes so many comment sections these days. The personal blog affords a certain level of civility and respect. If we disagree with each other — and we often do, thank God — we’re not going to call each other cunts or trolls or worse. At least not in public for everyone to see. We’re…classy.

So while my blogging has slowed, I’m not quite ready to give up on the platform yet. I still think there’s value in this mode of intellectual exchange — in the informality, the speed with which ideas can be exchanged, and, of course, the gifs.

So, what do you think (all 10 readers who are still reading)? Is the aca-blog dead? Does it matter? Did you like my gifs? Comment below. And please don’t call me a cunt.

Teaching this Old Horse some New Teaching Tricks

(from fanpop.com)

This semester I have experimented a lot with my teaching and classroom policies. While implementing new policies certainly adds more work (and frustration) to an already busy semester, my hope is to find the right mix of assignments and policies so that ultimately, running my class is less work and less frustration. One policy I tried out was changing my approach to student absences. In the past my absence policy has been that students could miss 3 classes over the course of the semester with no penalty. After 3 absences, I deduct 10 points (aka, a full letter grade) from their final grades for each additional missed class. Though I think this policy is quite generous, it created a lot of headaches for me. Students would be cavalier about missing classes early in the semester (missing 3 within the first 6 weeks of the semester) and then, when cold/flu season hit the campus (and it always does), they would miss even more classes and then beg forgiveness. I once had a student show up in my class looking like the Crypt Keeper. When I asked her why she came to class when she was clearly very ill and contagious she said that she had used up all of her absences and didn’t want to fail my class. Another student showed up to class drunk (very drunk) for the same reason. This led me to become the “absence judge, jury and executioner”: I would have to determine how the student would make up the additional absences in a way that was fair to the students who did the work and showed up every day . I also had to determine which truant students would have an opportunity to make up their absences. Does a sick aunt warrant missing 3 additional classes? What about a really bad break up? A court date?

from liketotally80s.com

This process is exhausting to describe and, I assure you, even more exhausting when experienced in real life. I have so much to do with my job and policing absences made me cuckoo-bananas. So this semester, after consulting with many other professors, I came up with a new plan. Students were still allowed to miss 3 classes without penalty. But then, I added this paragraph to my syllabus:

Students may “make up” missed classes by turning in a 4 page paper that describes, in detail, what was discussed in class during the missed day. This requires obtaining the notes of at least 2 classmates and piecing together the missed lecture/class discussion from these notes and from discussions with classmates (i.e., NOT me). If the missed class is a Tuesday, the paper should also discuss the reading assignment. If the missed class is a Thursday, the paper must discuss the week’s assigned film. This paper MUST be turned in within 2 weeks of the missed class. This is the ONLY way to “make up” a missed class. You must take care of obtaining notes from classmates on your own. After 2 weeks, the absence will be counted. THERE ARE NO EXCEPTIONS TO THIS POLICY.

This semester I had approximately 30 students and in that entire group, only 2 students missed more than 3 classes. One of the students missed many classes early on and took it upon himself to withdraw from my class. He actually apologized for his truancy and then said he hoped to try to take my class again in the future. There was no whining or pleading (and there usually is in these situations). He took responsibility for absences and removed himself from my classroom. I was actually shocked by how maturely my student handled the situation — it was kind of like interacting with a real adult! The 2nd student, who missed 4 classes, just turned in his make up paper. Again, this student did not attempt to make excuses for the classes he missed. He just turned in his paper and that was that. I say this because I have never had a semester at East Carolina University where students have attended classes so regularly. I could attribute this to the fact that I taught 2 upper-level seminars filled almost entirely with film minors who were invested in the class and its material — that probably helped. But I also think that having an absence policy that removed the weight of policing student attendance from my shoulders to their shoulders may have also helped. I also think that I have been making the mistake of coddling my students a bit too much. If I start treating them more like independent adults, they will act that way. Or at least, that is how it went down this semester.

The other change I made this semester was to the way I managed the students’ reading assignments. I had been finding that even in classes filled with my best students, there was a reading problem. That is, students weren’t doing the weekly reading assignments.

It got so bad last semester that I finally just asked my students point-blank “Why aren’t you reading?” And they told me. They felt the reading assignments were either too long or they didn’t see the need or value in reading them on the days when I didn’t go over the reading in detail in class ( in my day we did 50 pages of reading for a class, the professor didn’t discuss it with us and WE LIKED IT! but I digress….). So I listened to this feedback and changed things up. This semester I taught shorter essays (10-20 pages tops) and I also required the students to compose 3 tweets about the week’s reading and post them to Twitter every Monday, using the course hashtag. Here is an excerpt from the assignment I handed out at the beginning of the semester:

Guidelines for Twitter Use in ENGL3901

General Requirements

-You must post at least 3 tweets each week by 5pm every Monday (the earliest you may post is AFTER 5pm on the previous Monday)

For example:

-you must read the following short pieces by Jan 22 [Geoffrey Nowell-Smith “After the War,” pp. 436-443; Geoffrey Nowell-Smith “Transformation of the Hollywood System,” pp. 443-451]

so the tweets about that reading are due anytime BETWEEN 5pm on Jan 15th and 5pm on Jan 22

-You may do all 3 tweets in one sitting or spread them out over the course of a week

-All tweets MUST include the hashtag #E3901 so that the class (and your professor) will be able to see them

-All tweets must contain at least one substantial piece of information on or about the week’s reading assignment

As with the adoption of any new technology, there was a learning curve involved in using Twitter for classroom credit. Over half the students had never used Twitter before and therefore were not accustomed to its 140 character limit. I also had to send out weekly reminders for the first few weeks of class. But by the end of the semester I was surprised to see that the students kept up with this assignment and that they were actually processing the reading in useful ways. Being forced to take a complex idea and express it in 140 characters forces the student to engage with the material more deeply than if s/he had simply read the assignment and then put it down (or not read it at all!). I also think that having to account for their reading labor (and it IS labor) publicly — to the professor and to classroom peers — made the students realize the value and importance of the weekly reading assignments.

I actually wrote about this experience — as well as my experiences using blogs in the classroom — in a new short piece over at MediaCommons. If you’d like to learn more about the value of social media in the media studies classroom, you can click the link below. Please comment!

Click here to read “Mind Expanders and Multimodal Students”

So while instituting new policies has been time-consuming — both in planning, executing and documenting — overall, I am really happy with the results. I have a tendency to “mother hen” my students. I check in and remind them of deadlines, I poke and prod, and ultimately I wear myself out. I think I must wear them out too. Both the new absence policy and the incorporation of Twitter to encourage reading in the classroom has shifted some of those burdens from my shoulders to my students’ shoulders (where it belongs). This was most apparent when I realized that no one had emailed me this semester to explain why s/he had missed class and why I should count a particular absence as “excused” (in my class there is no such thing as an “excused” absence, unless the university tells me so). I feel like students took more ownership of attendance and engagement with their reading assignments. When I teach a 100-person Introduction to Film course this fall (a course with a notoriously high absence rate and low reading engagement rate), I will be interested to see how these new policies work. Til then though, I am going to go ahead and give myself a soul clap: