“To Dance Again!”: Affect, Genre, and the HARRY POTTER Franchise

This week I attended the annual Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Chicago. I decided to share the paper I presented there as part of the panel, “Affect in the Age of Transmedia Storytelling” on this blog in an effort to make research that was presented to just 20-25 people (not a bad turn out for one of the first panels of the 5 day conference!), available for a wider audience. My paper was originally titled “‘Falling in Love with Hermione Granger’: Affect, Genre, and the Harry Potter Franchise” but I ultimately did not have time to discuss the song, “Granger Danger” in this brief paper (a note that drew at at least one “Booooo!” from the audience when announced), so I changed the title for this post to reflect that omission.

To watch “Granger Danger” start at the 2 minute mark

Other than the title change and some added clips (yay internet!), the paper below is what I presented last Wednesday. I welcome any feedback.

********

“To Dance Again!”: Affect, Genre, and the Harry Potter Franchise

I want to begin this discussion of affect in the transmedia franchise by discussing a scene from A Very Potter Musical, a full length stage musical written, directed and performed by a group of University of Michigan performing arts students and recorded and broadcast online via YouTube in 2009. The show has 14 original numbers and over 9 million page views. The scene you are about to watch is a recreation of a significant moment from JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire –when Lord Voldemort finally reclaims a human body after more than 11 years of painful disembodiment. What is the first item on Voldemort’s evil agenda? Why, to dance of course!

Begin watching “To Dance Again!” at the 3 minute mark:

In this number Voldemort usefully describes how music can compel the body to dance, even when the brain rejects the idea:

“The other boys would laugh and jeer

But I’d catch em tappin their toes.

‘Cause when Id start to sway

they’d get carried away.

And oh, how the feeling grows…”

These lines—and the whole number for that matter, highlight the relationship between affect and music—how the compulsion to sing or dance is frequently pre-cognitive.

In “Serial Bodies,” Shane Denson defines affect as “the privileged but fleeting moments, when narrative continuity breaks down and the images on the screen resonate materially, unthinkingly, or pre-reflectively with the viewer’s autoaffective sensations.” Denson then goes on to cite Linda Williams’ famous essay on body genres, “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess,” in which she argues that when watching horror films, pornography or melodramas, “the body of the spectator is caught up in an almost involuntary mimicry of the emotion or sensation of the body onscreen” (144). Though Williams makes a passing reference to musicals in her list of potential body genres, the musical is rarely discussed in terms of its relationship to affect. However, the instinct to sing or dance to a catchy tune is frequently takes place just before our conscious mind reminds us that such an impulse could lead to public humiliation.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2012/oct/29/horror-movies-help-burn-calories

I am also using affect in this talk to reference the very real emotional connections between fans and the texts they love. In fact, the syntax of the musical favors emotion in that the genre’s most valued characters are those who sing and dance because they love it so much–because the pure bliss of performance cannot be resisted. Those characters who sing and dance purely for money or who overthink their art are usually proven to be villains, or at the very least, in need of reformation.

For example, in The Bandwagon (1953), Jeffrey Cordova (Jack Buchanan) is only able to create a successful show when he stops aiming for “high brow” status and just makes a show filled with music and dance:

So what does a singing and dancing Lord Voldemort have to do with transmedia franchises and affect, the subject of today’s panel? By translating key plot events from the Harry Potter franchise into musical numbers, I am arguing that A Very Potter Musical transforms the fantasy franchise’s key opposition between good and evil to the musical’s own preoccupation with joie de vivre over monetary gain. In her study of Roswell fandom and genre in fan discourse, Louisa Stein argues that fans “use generic codes as points of identification with story and character, making fictional narratives and characters personally meaningful or resonant through processes of genre personalization” (2.4). Likewise for fans of the musical, A Very Potter Musical offers an affective entry point into the vast narratological universe of Harry Potter, making the franchise more personally meaningful. This is not to say that Potter films and books don’t generate affect in their audiences, but rather that the structures of the musical create new opportunities for affect among Potter fans (and of course, for Potter fans who dislike musicals, AVPM will not provide any form of engagement because they won’t seek it out).

As a transmedia franchise that includes 7 novels, 8 blockbuster films, a Disney theme park, toys, videogames and countless other product tie-ins, Harry Potter fandom is necessarily broad, heterogeneous, and expressed through a range of media platforms: thousands of fan-created websites, newsletters, slash, conventions, a thriving genre of Harry Potter-themed rock music known as “wrock,” and even an activist group known as the Harry Potter Alliance. A Very Potter Musical, which seems to straddle the spaces between fan fiction, wrock, and possibly even filk, disguises its budget limitations with winking musical performances, self reflexivity, and the unabashed passion of its actors. Fan love fills in production gaps and adorns the visible seams of this otherwise amateur production. The lengths that fans will go to express their adoration for a beloved text have been well-documented by fan studies scholars like Henry Jenkins, who describes fan fiction as “a celebration of intense emotional commitments and the religious fervor that links fandom to its roots in fanaticism” (251). Thus for scholars of fan studies, AVPM is nothing new. However, for a scholar of film genres like myself, the show is quite useful for understanding the role that genre—specifically the musical–plays in the relationship between fandom, transmedia franchises and affect.

Watch Darren Criss (Harry Potter) and Joey Richter (Ron Weasley) perform “Goin Back to Hogwarts” with some fans. Note the moment when the fans chime in at the 55 second mark and Darren Criss’ reaction:

One way that AVPM creates an intimate relationship between fan and text is by transforming the multibillion dollar Harry Potter transmedia franchise—the ultimate form of mass culture–back into folk culture. Whereas folk art is an expression of the community who is also its audience, mass art is disseminated to its audience already made, articulating its values for them. However, as so many fan studies scholars have noted, fan fiction allows fans to convert mass culture back into folk culture. I would add that by explicitly relying on the syntax and semantics of the musical, AVPM is even more adept at creating the sense that mass art is folk art. Jane Feuer argues that: “In basing its value system on community, the producing and consuming functions served by the passage of musical entertainment from folk to popular to mass status are rejoined through the genre’s rhetoric” (3).

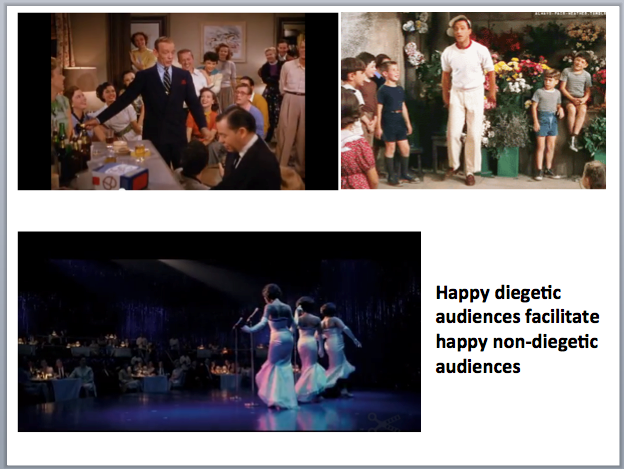

For example, film musicals often offer up images of the diegetic audience to compensate for the “lost liveness” of the stage, serving as a serving as a stand in for the film audience’s subjectivity (27). Many Hollywood musicals include a diegetic audience that cues the non-digetic audience in about how to feel about a performance—if they clap and cheer, the performance was successful. If they sit silently in their seats, the performance was a bust. A similar effect is created when watching the streaming video of the live stage performance of AVPM. As you heard in the “To Dance Again!” number, the laughter, applause, and hoots of appreciation stemming from the live, diegetic audience solidifies the non-diegetic audience’s understanding that these low budget performances are, in fact, successful — even when it is difficult to hear some of the actors’ lines and jokes are lost. This is especially important for something broadcast over the internet, since most viewers of AVPM are likely watching on their computer screens, alone. The diegetic audience thus serves as a viewing companion, reassuring us about when to laugh or applaud.

Likewise, Feuer argues that many musicals include characters who are not supposed to be professional singers and dancers but who instead sing and dance for the love of it. This use of “amateurs” gives us the feeling that stars are singing and dancing on screen because they love to, not because they are being paid to do so. By masking this professionalism, the musical’s performers are closer to us, the amateurs in the audience. AVPM offers a similar experience, only the performers we are watching really are amateurs in that the show itself is a labor of love rather than a profit-generating venture.

This feeling is bolstered by the show’s shoddy production values. For example, in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the evil Lord Voldemort attempts to revive his body by attaching what little remains of his soul to the simpering Professor Quirrell. In the book, and even more so in the film adaptation, this melding of two men—skull to skull–is a horrifying spectacle. However, in AVPM the inability to create a CGI monster and the need to improvise becomes one of the show’s best gags.

We marvel, not at Rowling’s fantastical prose nor at the wonders of CGI, but at the cleverness of the students who have put on this show.

Watch the big reveal here:

When watching AVPM the amateurish costumes and sets, the imperfect sound and image quality, and the occasional mistakes, lets us know we know we are watching Harry Potter fans who are just like us—rather than seasoned professionals. Such moments work, to quote Feuer again, to “pierce through the barrier of the screen” (1). So while AVPM is not spontaneous (clearly it was rehearsed and well though-out), its imperfections create the feeling of spontaneity, which is so central to the task of making mass art appear as folk art. Furthermore, Glen Creeber argues that the rawness of online video and the solitary viewing conditions it generates creates a sense of intimacy and authenticity not found in cinema or television. He argues that the “homemade” aesthetic of webcam images creates the “profound intimacy of the image” (598).

Watch Harry Potter face off with a Hungarian Horntail at the 1 minute mark:

In addition to creating intimacy between fan and text, A Very Potter Musical—due to the genre’s focus on the joys of song–creates an affective relationship between viewer and text. For example, in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Harry Potter’s participation in the Triwizard Tournament leads him to engage in battle with a Hungarian Horntail, a fierce breed of dragon. Harry ultimately defeats the Horntail with his exceptional broom-flying skills. And in the film adaptation, we get to see this fantastical scene come to life through the magic of CGI. However, in AVPM, Harry defeats the dragon by summoning his guitar, not his broom, and then by performing an emo ballad about the futility of hand-to-hand combat entitled “Hey Dragon”.

Watch the number here:

The song concludes with the lyrics:

“I can’t defeat thee

So please don’t eat me

All I can do

Is sing a song for you.”

The dragon is eventually lulled to sleep by Harry’s song. Harry thus relies on the power of music—rather than magic—to win a seemingly insurmountable challenge. So while this musical number is a practical way to disguise the absence of state of the art special effects, it also highlights the way that music can impact the body, turning a fierce dragon into a purring kitten. The consumption of spectacle is a pleasure central to the Potter franchise but in AVPM these are replaced with the pleasures of musical performance.

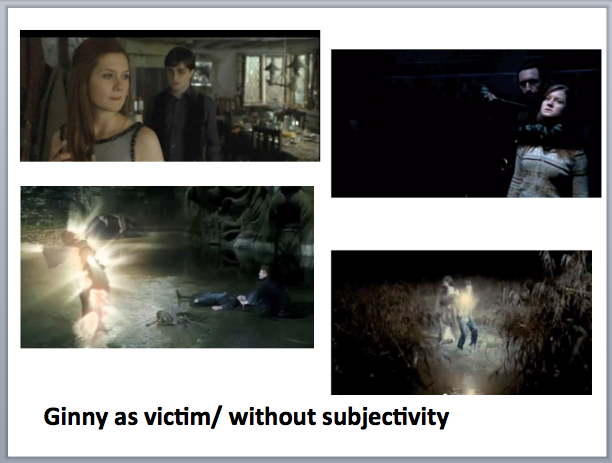

Like most examples of fan fiction, AVPM also highlights aspects of the Potterverse that may not be apparent in the novels, films and officially licensed paratexts, but which fans desire. For example, in the books, secondary character Ginny Weasley is defined almost entirely in relation to her older brother, Ron, and her love interest, Harry. Likewise, Ginny’s romantic relationship with Harry is primarily understood through Harry’s point of view. For example, in Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince, Rowling describes Harry’s budding feelings for Ginny in this way:

Likewise, the films cue us in to Harry’s desires via longing close ups or by frequently putting Ginny in a position to be rescued by Harry. This is such a prevalent plot twist, in fact, that wrock band Harry and the Potters wrote a song about it:

The fan knows little of Ginny’s interiority, other than through bits of dialogue or the occasional longing glance at Harry:

In AVPM, however, Ginny performs the torch song “Harry,” which puts a literal and metaphoric spotlight on what it feels like to be in love with the Boy Who Lived.

Watch “Harry” here, performed by Ginny Weasley (Jaime Lyn Beatty)

Ginny’s moving performance, in which she dances awkwardly with Harry’s guitar—a proxy for her absent love object—provides a renewed emotional connection with this secondary character. And Ginny’s performance—which is passionate but imperfect as she struggles to hit her big notes—creates an affective relationship with this character that may not have been possible when watching the Potter films. The goosebumps that appear on my arms as Ginny sings, are a testament to the way that music generates an affective viewing experience.

Here again we can see how the choice of genre—the musical—allows Potter fans an entry point into the transmedia franchise that is personal and intimate. Indeed, there are numerous covers of “Harry” on YouTube, a testament to the way that AVPM allows Potter fans a different, more embodied way, to express their fandom.

Watch my favorite fan covers of “Harry” here:

One thing all of these performances share is a nervous, almost giddy, sense of joy—we can trace the joy expressed in the original AVPM performance as it is then translated and transmuted through each fan video—a domino effect of pure love. Likewise, the comments on each video are generally supportive, with the Potter fan community coming together to support each new iteration of the original fan text.

In this way, AVPM fandom appears to mimic that of the wrock community. Suzanne Scott argues that wrock, unlike filk, “mimics a conventional performer/audience dialectic rather than a collective creative enterprise when performed.”

Although there is a separation between performer and audience here, I believe that the significance of AVPM lies in the affective relationships it facilitates between fan and text, even if the text’s various performers are performing online with one another, as opposed to face to face in a filk song circle.

In conclusion, A Very Potter Musical translates the fan’s love of the Harry Potter storyworld and its characters into a series of musical numbers that fans can then sing themselves. By depicting bodies that must express themselves through song and dance, A Very Potter Musical is an ideal venue for understanding the importance of affect in fan fiction. AVPM demonstrates the way that mass culture can be transmuted back into folk culture, thereby offering fans of the transmedia franchise a personalized, emotional engagement.

Works Consulted

Creeber, Glen. “It’s Not TV, it’s Online Drama: The Return of the Intimate Screen.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 14.6: (2011): 591-606

Denson, Shane. “Serial Bodies: Corporeal Engagement in Long-Form Serial Television.” Media Initiative 22 Feb 2013 http://medieninitiative.wordpress.com/2013/02/22/serial-bodies/

Feuer, Jane. The Hollywood Musical, 2nd Ed. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1993.

Jenkins, Henry. 2012. “‘Cultural Acupuncture’: Fan Activism and the Harry Potter Alliance.” In “Transformative Works and Fan Activism,” edited by Henry Jenkins and Sangita Shresthova, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 10. doi:10.3983/twc.2012.0305.

——-. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

———. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Rowling, JK. Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince. New York: Scholastic Inc., 2005.

Scott, Suzanne. “Revenge of the Fan Boy: Convergence Culture and the Politics of Incorporation.” Diss. University of Southern California, 2011. Online.

Stein, Louisa Ellen. 2008. “Emotions-Only” versus “Special People”: Genre in fan discourse. Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 1. http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/43.

Tatum, Melissa L. 2009. “Identity and authenticity in the filk community.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2009.0139.

Williams, Linda. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre and Excess.” The Film Genre Reader III. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003. 141-159.

March 12, 2013 at 10:33 am

Thanks for posting your SCMS talk, which I missed due to a snowstorm-related flight cancellation. So it was nice to be able to read it here. I hope more people will follow suit, as there were just too many concurrent panels at the conference, and so impossible to see everything of interest. Thanks also for the shout out to my paper on TV seriality and affect theory. And in case you missed it, I’ve posted my own SCMS paper (on post-cinematic affect) here:Thanks for posting this here. I missed hearing your talk at SCMS, so I’m happy to have the chance to read it here. Really an excellent paper!

In case you’re interested, I’ve posted my own SCMS talk here: http://wp.me/p1xJM8-pX

November 27, 2013 at 11:42 pm

It has been also been honored as ‘Las Vegas’ Best Production Show’.

This is not an impossible challenge, but a difficult one.

Bugsy had to negotiate and force his way into the Flamingo property.

June 10, 2014 at 12:03 pm

I am actually grateful to the holder of this web site who has shared this wonderful paragraph at at this place.