Academia

GHOSTBUSTERS as Neoliberal AltAc Fantasy

http://www.vulture.com

Normally, I’m not a big fan of rewatching films I’ve already seen. I have to do so much rewatching for my classes and for my research that in my free time my goal is to see new stuff. Nevertheless, over the last few months I’ve been rewatching some favorite films from my childhood, like Home Alone (1990 Chris Columbus), Mrs. Doubtfire (1993, Chris Columbus), Teen Wolf (1985, Rod Daniel), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986, John Hughes), Karate Kid (1994, John G. Alvidsen), and Footloose (1984, Herbert Ross), with my own children and I’ve been surprised by how much I’ve (mis)remembered those films. When I rewatched Mrs. Doubtfire, for example, I was shocked by how my memories of that film were so conditioned by its theatrical trailer. The scenes that I found myself remembering before they happened — Robin Williams asking Harvey Fierstein to make him a woman, Robin Williams throwing a piece of fruit at Pierce Brosnan’s head, Robin Williams’ rubber breasts on fire — were the scenes that were featured in the film’s trailer:

As a child of the 1980s, I grew up with commercials, with flow, and I watched these commercials over and over, even when I didn’t actively watch them (because I was fighting with my brother or gabbing on my sweet cordless phone). These scenes travelled through my brain repeatedly, wearing a groove, making themselves at home. Robin Williams’ burning rubber breasts are a permanent part of my memories.

But it wasn’t just frequent exposure to trailers that shaped my memories of these films — my memories have also been shaped by the way I watched movies as a child, that is, by my child-self’s attention span. A few weeks ago we decided to screen Footloose for our kids, reasoning that its numerous dance scenes would make up for its snoozer of a plot about an uptight preacher (John Lithgow) who won’t just let those kids dance! But my husband and I misremembered the film — there aren’t that many dance scenes in the film. And when those kids aren’t dancing? Well, the film is pretty boring. Our kids (and our neighbor’s kid) were antsy throughout, only pepping up when a dance number came on. Then they would leap off the couch and dance furiously until the narrative started up again. So perhaps they, too, will misremember the film when they’re old like me, filing away the “good stuff,” the dancing and the Kevin Bacon, and forgetting the boring stuff.

What I’d like to talk about in this blog post, though, is my experience of rewatching a beloved film from my childhood and realizing that the film my child’s brain watched is very different from the one I watched as an adult. I’m talking about Ghostbusters (1984, Ivan Reitman). I remember being 8-years-old and actively anticipating the release of Ghostbusters, a movie which was most certainly a must-see for the elementary school set. Like most kids my age, I was obsessed: I watched the sequel and the Saturday morning cartoon, ate my Slimer candy, and of course I drank my fair share of Ecto Cooler .

This past Saturday we rented Ghostbusters, made some popcorn, and invited another couple and their son to watch it with us (at this point my child-free readers might be asking themselves: is this what Saturday night looks like when you have young children? Yes it does, child-free friends, so please, practice safe sex). As we all sat down to watch the movie, the first thing I remembered about the film, or rather what I had forgotten about the film, is that before they become “Ghostbusters,” saviors of New York City (and by extension, the entire world), Peter Venkman (Bill Murray), Raymond Stantz (Dan Ackroyd) and Egon Spengler (Harold Ramis) are actually professors at Columbia University, studying the paranormal.

Image source:

ghostbusters.wikia.com

I had completely forgotten this but the moment the film cuts from a frightened librarian to the interior of a Columbia lab where Bill Murray flirts with a student participanting in his ESP tests, I turned to my children and declared “The heroes of this movie are professors, kids, just like Mommy!” The friends who were over are also professors, in Biology and Geology, so they were also excited for their son to see professors doing cool shit in a movie (this rarely happens, as you all know). After we watched the scene in which the professors are informed that their grant has been terminated, my daughter was confused “What just happened?” she asked. I explained, “It would be like if Beth’s boss took away her corn fields or if Eric’s boss took away his rocks.” Then my husband piped in “Or if someone said Mommy couldn’t watch movies.” Rocks and corn are not ghost busting, but they’re more tangible than the study of film. Nevertheless, this answer satisfied my daughter.

As I watched Venkman, Stantz, and Spengler pack up their offices and their life’s work and leave Columbia’s grand campus, I thought about the current state of academia and then, I began to watch Ghostbusters in a different way. Instead of watching the fun, comedy-horror-blockbuster of my youth, I found I was watching a vision of the future of academia, a fantasy of the Alternative-Academic career, one based wholly on the market value of the university professor’s research, rather than the broader, and somewhat less market-driven value of the professor’s ability to instruct students in that research and to engage the public in those findings.

Image source:

http://www.clearancebinreview.com/

When the professors leave academia they are not ghost busters. They’re just unemployed PhDs, which, as we all know, are a dime a dozen. What transforms these useless, unemployed academics into Ghostbusters? An ancient Sumerian god named Gozer the Gozerian, who wants to destroy New York City! These professors are literally the only people in the city who can do this job. They actually have ghost busting equipment: proton packs (for wrangling ghosts), ghost traps, and an Ecto containment unit on hand. I mean if there’s something strange in your neighborhood who are you gonna call? I don’t need the 1984 Ray Parker Jr. hit to answer that question, because the answer is, naturally: GHOSTBUSTERS! The university may not value these men, but the good people of New York certainly do. Their research will save the world! Does your research save the world? Mine sure doesn’t!

So you see, these professors have a real value. As soon as their first commercial airs, glimpsed (fortuitously) by beautiful Dana Stevens (Sigourney Weaver) just before she finds a demon in her fridge, the phone at Ghostbusters central never stops ringing. In fact, the Ghostbusters have so much business, they must hire a fourth ghost buster, Winston Zeddemore (Ernie Hudson). My childhood memories of this film have Hudson’s character, aka the “black Ghostbuster,” playing a much larger role, perhaps because he gets more screen time in the sequel? But during this viewing at least, I was surprised by how little screen time he gets. His character truly feels like an afterthought, like a producer said “You better get a black guy in there somewhere” and so they threw him in at the last minute. But I digress. All of this is just to say that business is booming at Ghostbusters and the men are finally getting the chance to prove the value — the real, incontrovertible value — of their life’s work. The market says so.

In this neoliberal (a term I use here to reference the broader trends toward the privatization of higher education) fantasy of higher education, academia within the walls of the academy is stifled and limited. But once professors are freed from the constraints of the Ivory Tower, with its navel-gazing and its pretentiousness, and are placed at the mercy of the market (aka, “the real world”), they can demonstrate the true value of their research and their pedagogy. Professors should be training our college graduates for real jobs in the real world. After all, isn’t the whole point of a university education to create future workers, future entrepreneurs, future moneymakers? Sure it is.

But what happens next? What interrupts our fairytale of flourishing academics? It’s the goddamn Environmental Protection Agency, that’s who! Walter Peck (William Atherton), the EPA representative, is the film’s heavy. I remember hating this character when I was a kid. “Why won’t he just let the Ghostbusters do their jobs? Doesn’t he realize the fate of the city is at stake? Regulation is the worst!” Peck wants to investigate the environmental impact of the Ecto containment unit, which, I have to admit, looks super shady. I wouldn’t want to live downstream from the Ecto containment unit, but if I had to choose between living with Gozer and living with Ecto in my water? Bring on the Ecto cooler! Screw the EPA! Regulation, boo, hiss!

In the final scene of Ghostbusters, all four men (yes, even Winston), are cheered by New York City residents who are grateful that they’ve been saved from the wrath of Gozer. I told my kids “Look, they’re cheering for the professors!” And then the four adults in the room laughed for a long time.

My kids laughed too. They were delighted by the film, just as I had been as a kid. But this time around, Ghostbusters gave me pause. The narrative hit a little too close to home because I am acutely aware of the market value of my degree and my profession. My Governor tells me my work is useless and elitist. So I’m waiting for the day when this dystopian future is upon us, when the key master finds the gate keeper, and we’re all packing up our offices, just waiting for a chance to prove our true worth.

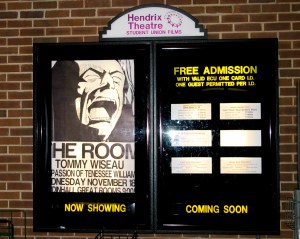

Screening THE ROOM: 2012

Note: I have been given permission by the students of ENGL4980 to use their images in this post.

Hey there, you. Yes, I’m talking to you, my dear reader. I know it’s been three months since my last post. That doesn’t mean that I forgot about you. In fact, there has been a blog-sized hole in my heart these last few months that I have been aching to fill with my gob-smacking insights into film and television. But now I’m back. And I’ve brought you chocolates and roses. Or rather, I’m bringing you a post about chocolates and roses and rain-slicked windows and “sexy” red dresses and lots and lots ham-fisted performances and green screens and unexplained establishing shots and tiny doggies and alley football. In other words, I’m bringing you a post about screening The Room...[insert dramatic music]…2012!

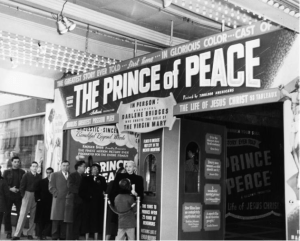

I came up with the idea of having my student run their own cult film screening when I first taught ENGL4980 “Topics in Film Aesthetics: Trash Cinema” in the Fall of 2009. The course objective was to examine the aesthetics of films which were notorious, not for their excellence, but for their terribleness. In “Esper, the Renunciator: Teaching ‘Bad’ Movies to Good Students,” Jeffrey Sconce argues: “beach blanket films, Elvis pictures, 1950s monster-movies — any film where history and technique remove students from the ‘effects’ of representation and plunge them headlong into the quagmire of signification itself” can be fruitful classroom texts (31). The polished Hollywood stalwarts that populate the syllabi of so many film studies courses — Casablanca (1942, Michael Curtiz), Citizen Kane (1941, Orson Welles), Vertigo (1958, Alfred Hitchcock) — are so seamlessly crafted and carry the weight of so much critical praise that it is often difficult for students to find a way to analyze their “invisible” style. Of course, I do teach these films in other classes (one film I will always teach in Intro to Film is Casablanca –always and forever). But I think it’s useful for film studies students to also look at films with a highly visible style — ideally one in which all of the seams are showing. Further, understanding how and why we classify popular culture as being in “good” or “bad” taste tells us a lot about how unnatural and constructed such categories can be. These are topics that can often be easily ignored when we only watched Ingrid Bergman framed in a beautifully lit close up.

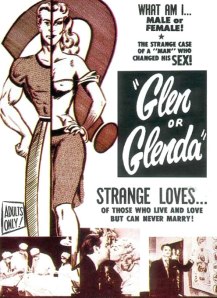

Throughout the semester my students and I have been studying American films that have been marginalized due to a variety of interrelated factors: their small budgets and chintzy set designs (Sins of the Fleshapoids [1965, Mike Kuchar]), their completely inept style (Glen or Glenda? [1953, Ed Wood, Jr]), their offensive subject matter (Pink Flamingos [1972, John Waters] and Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story [1987, Todd Haynes]), their violent or sexual imagery (2000 Maniacs [1964, Herschell Gordon Lewis] and Bad Girls Go to Hell [1965, Doris Wishman]) and their desire to place marginalized faces at the center of the screen (Freaks [1932, Tod Browning] and Blacula [1972, William Crain]). In addition to understanding why these films have historically been viewed as “trash” (we relied heavily on Pierre Bordieu’s pithy line “Taste classifies and classifies the classifier” to answer this question) we also sought to understand why moviegoers persist in watching these movies. This second question is, admittedly, harder to answer. Why did my students enjoy watching the blurry, overdubbed images of Todd Haynes’ Superstar or delight in the conclusion of Sins of the Fleshapoids when (SPOILER ALERT!) a female “fleshapoid” gives birth to her own baby toy robot?

Watch a fleshapoid give birth to the fruit of her forbidden robot love.

Enter The Room. I will admit now that the idea for this assignment was partially selfish: I had read about The Room and wanted to experience a live screening myself. Right here in my own town! Of course, beyond my desire to scream the holy words “YOU’RE TEARING ME APART, LISA!” with a crowd of rambunctious moviegoers, I also felt that this assignment would be an inventive way of having my students learn by doing. The fancy word for that is “praxis.” You’re impressed now, aren’t you?

I had a few goals with this class project:

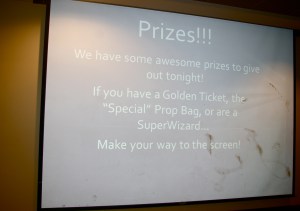

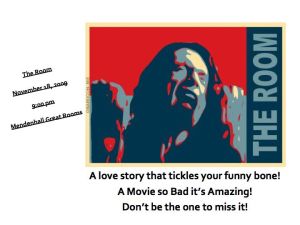

1. To teach students about the importance of “ballyhoo”

Eric Schaefer defines ballyhoo as “that noisy, vulgar spiel that drew audiences to circuses and sideshows…a hyperbolic excess of words and images that sparked the imagination” (103). Ballyhoo promises audiences something—an image, an experience or a reaction (“This movie will make you puke!”)—that it does not always fulfill. This unfulfilled promise is a convention of exploitation advertising. I encouraged my students to think of their advertising in this way — as an exaggeration or complete misrepresentation of the experience of attending The Room. Say whatever you need to say to fill the theater seats.

I told the students that their grade for this project would be partially determined by the amount of people in the audience and the level of enthusiasm emanating from the audience during the screening. Just as exploiteers like Kroger Babb and David Friedman endeavored to fill as many theater seats as possible because their livelihoods depended on it, my students had to fill the theater or risk a low grade. The students were given the duration of the semester to design and distribute posters, create a buzz in various forms of media, and prepare the venue for the night of the screening — just as their exploiteer ancestors did.

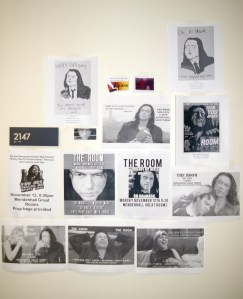

They made a variety of posters and flyers:

They created a Facebook event page and posted regular reminders extolling the virtues of The Room:

They created a series of “Golden Tickets” which they planted around campus. Students who located the tickets and attended the screening received a “special” prize which I believe was just a ring pop. But you see: that’s exploitation!

The students also convinced the school paper, The East Carolinian, to write an article about our event and called the campus radio station to plug the screening after the Presidential election. Overall, I found their ballyhoo to be creative and persistent, which is key to the successful exploitation of a film. Indeed, about 15 minutes before the start of the screening, when it appeared as if they would not fill the theater, several of my students ran outside the venue to harass students as they walked by: “Don’t you want to come and watch The Room? It’s the greatest movie ever! We’ll give you spoons!” That’s exploitation too! Lesson learned, students. Lesson learned.

2. To teach students about how cult film audiences are created and nurtured

This was the trickiest aspect of the class project because a cult audience is defined by its almost spontaneous nature. A cult is created by the audience, not by a group of students hoping to score an A in the film studies class that they’re taking to fulfill their Writing Intensive requirement for graduation. We watched The Room during our first full week of class and the campus-wide screening did not take place until the 13th week of class, so by the night of the screening I think my students were legitimate enthusiasts. But what of the audience members who had been lured into the theater on a Monday night, through false promises that the event would be the screening event of a lifetime or because their friends in the class had begged them to or because they were promised special prizes?

Could a group of students (the majority of whom had never seen The Room prior to enrolling in my course) create a cult film audience out of sheer force of will? I think they did.

It was the students’ responsibility to prepare the audience for the evening’s events through their promotional efforts and also by presenting a brief introduction to the film. Ostensibly motivated by the desire to educate, exploiteers would often bring in “experts” (or actors dressed as doctors and nurses) to speak to audiences who came to watch their sex hygiene or drug films. But of course, this was titillation in the guise of education, further adding to the experience of watching the film (which started the moment an audience member saw the first advertisement in the local paper). We attempted to replicate this environment by having one of the students serve as an emcee. She provided the audience with insight into the cult of The Room and a demonstration of key rituals. Our emcee cracked jokes and interacted with the audience throughout her introduction, which prepped the audience for the film to come.

The students were also tasked with assembling prop bags for the audience and deciding on what rituals they wanted the audience to perform (again, a seemingly antithetical concept in the world of interactive screenings). They repeated some of the most basic rituals of The Room — the throwing of spoons, the shouting of “Because you’re a woman!” every time Lisa offered up an excuse for her duplicitous behavior, and the calling out of “Hi Denny! Bye Denny!” — but they also added a few new rituals. First, during each of the film’s lengthy and grotesque lovemaking scenes, my students wandered through the audience with bunches of fake red roses (because the film’s protagonist, Johnny, and his fiance, Lisa, make love on a pile of roses). They would tap an audience member on the shoulder and whisper “Welcome to the sex scene. Please accept this rose.” It’s already uncomfortable watching Johnny make love to Lisa’s belly button but to have someone offer you a rose during such an awkward scene heightens those feelings. The second ritual they added was to release several garbage bags worth of balloons during the film’s climactic (and lengthy) party scene. Once the balloons were released, the audience began to bat them around (they would pop after hitting the ceiling), thus bringing the on-screen party into the audience:

On a side note, I should add that the students also purchased a small pack of glowing, LED-filled balloons, which they thought would be a fun addition to this ritual. However, upon reading the instructions the students discovered that these balloons were potentially dangerous when popped and had to be safely “detonated” after use. This added a little, personalized thrill to the screening for me as every time I heard a popping noise I wondered if I might lose my job because a student had just been blinded. That’s exploitation too! Way to go, students!

3. To teach students about the joys (and frustrations) of a class project

In the classes I teach there is rarely a good reason to assign a class project. However, this screening assignment afforded me a truly useful reason to force my students to work together — to create an environment in which it is safe for me to hurl curses at a screen for 100 glorious minutes. As I mentioned, part of the students’ grades for this project was going to be determined by the amount of people they could convince to attend the screening as well as the enthusiasm of the audience (after all, a cult film audience who sits silently is no kind of cult film audience at all). This meant that if the event was a bust, the grades were a bust too. In the weeks leading up to the screening, I witnessed more and more cohesion among my 14 students. They conferred before and after class, collecting in corners of the classroom to share flyers and advertising ideas. Indeed, on the night of the event I noticed a change in the dynamic of the group. I stood back and watched as they arranged prop bags, fiddled with their power point, psyched up the event’s emcee, and of course, fretted over whether or not the evening would be a success. True, I felt a little like the judge, jury and executioner throughout all of this — in the hour leading up to the screening I caught students eyeing me nervously — but I also felt very proud of them. Moments before the event started we gathered for a class huddle and shouted “YOU’RE TEARING ME APART LISA!”

In short, I was delighted with the results of this student project. I think students learned — first hand — what it would be like to be an exploiteer whose livelihood depended on generating enough ballyhoo to fill a theater. I think they also learned about the joys and rewards of cult viewership even if the viewership they created was highly constructed and mediated through the lens of a class project.

Below I would love to hear about any successes (or failures) you’ve had in attempting to implement class projects into the film or media studies classroom. Were these projects simply “busywork” or do you think they helped your students to gain a greater understanding of the course material?

Works Cited

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Trans. Richard Nice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Schaefer, Eric. “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!”: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

Sconce, Jeffrey. “Esper, the Renunciator: Teaching ‘Bad’ Movies to Good Students.” Defining Cult Films: The Cultural Politics of Oppositional Taste. Eds. Mark Jancovich, Antonio Lazaro Reboll, Julian Stringer, and Andy Willis. Manchester: Machester University Press, 2003. 14-34.

Work, Study and Scholarship as an Academic Parent, Part II: Parenting on the Job

A few weeks ago I published Part 1 of a two-part post entitled “Work, Study and Scholarship as an Academic Parent, Part I: Grad School Babies.” This post covered the presentations and discussions that took place during a workshop that I chaired at this year’s Console-ing Passions: A Conference on Television, Audio, Video, New Media, and Feminism, hosted by Suffolk University, entitled “Work, Study and Scholarship as an Academic Parent.” This post discussed the challenges and rewards of having a child while still in graduate school. I was pleased to see how many people engaged in this conversation — in the comments section of this blog, on Facebook, and on Twitter. I often feel self conscious whenever I link up my roles as parent and professor since acknowledging that one role might impact the other implies a weakness. It makes me a less desirable employee than my child-free counterpart. Thus, the first rule of being an academic parent is don’t talk about being an academic parent. I also worry about alienating ,or at least annoying, my child-free friends and colleagues with posts like these — I don’t want anyone to “un-baby” my blog. Wait, you’re doing it right now, aren’t you? Okay fine. Here’s a picture of a kitten:

In all seriousness, I think these conversations are important for all academics to have, even those who never plan to have children. We all need to work together, after all, and we need to find ways to accomodate each other and create policies that help us all to be the best scholars, teachers, and yes, committee-members, we can be. As my lovely colleague, Anna Froula put it:

“I want the colleagues I work with to be happy at work (so they’ll keep working with me), so it’s a quality of life issue. The reason I defer to [colleagues with children when] scheduling meetings is because, simply put, you have more humans in your family that depend on you to balance work and home life. My time is more flexible because I don’t have kids. If one of us had an ill parent or some other pressing issue to deal with, it would be the same thing. We should want to take care of each other so we can enjoy working together and do so efficiently.”

Like Anna, I want us all to enjoy working together. To that end, this post will replace all cute baby pictures with cute animal pictures. But be warned: my Facebook page remains fully babyfied.

*****

“The ‘Child Friendly’ Department: Definitions and Expectations”

In this post I’ll be summarizing the portions of the workshop that covered parenting after graduate school. In many ways, the life of a college instructor is ideally suited to the rhythms of parenting. We have the option to take our summers “off” (though for me, “taking the summer off” means I don’t teach but I do continue to research, write, and work on my fall syllabi and course plans). Most teaching schedules are confined to a Tuesday/Thursday or Monday/Wednesday/Friday schedule, which allows parents to work from home at least one or two days per week (unless they hold an administrative position). And most college courses are over by 4:00 pm or 5:00 pm, which allows parents to be home when their kids are finished with school for the day. Pretty sweet, right? Well, maybe not. In their article, “Care, Career, and Academe: Heeding the Calls of a New Professoriate,” Nikki C. Townsley and Kristin J. Broadfoot argue that “…short-term flexibility obfuscates the long term inflexibility of academia for faculty committed to both work and family.” Here are some examples:

* women who get TT job before having kids were less likely to become mothers or get married and were more likely to be divorced or separated.

* female academics were found to hold the highest rate of childlessness amongst professional women at 43%.

* the tenure track model supports a progressive, linear and seamless career model in that many TT jobs expect professors to teach full course loads, be on several committees and publish at least one book in the 1st 5 years on the job.

* in fact, TT job expectations are built on presumption that professor has a full-time home-based caregiver and homemaker. The university is not structured to accommodate dual career families.

These statistics beg the question: is being an academic parent harder for women than it is for men? In “Does it Take a Department to Raise a Child?” Bonnie J. Dow writes that lack of support for pre-tenure parenting negatively affects careers of female junior faculty more than male junior faculty. Here are some of her findings:

*12-14 years after obtaining PhD, males on the tenure track in the humanities & social sciences with “early babies” (babies born in the first 5 years after finishing the PhD) receive tenure at rate of 78%.

* 58% of women in same position receive tenure.

*women with “late babies” (babies born more than 5 years after the PhD) received tenure at a rate of 71%.

*47% of women reported great deal of tension and stress over parenting/work conflict versus 27% of men.

Dow’s findings indicate that many female professors are unable to fulfill the requirements of tenure while parenting a young child. The later women wait to have a baby, the better their chances for tenure. But male parents don’t face the same problems. They have an easier time having successful academic careers while having families. Indeed, Dow’s article mirrors many of the points made by Anne-Marie Slaughter in her hotly contested piece in The Atlantic from earlier this summer. In her article, entitled “Why Women Still Can’t Have it All,” Slaughter argues that women have a harder time being mother-workers than men do. I know there was a lot of blowback on this piece but Slaughter makes a lot of great points. For example, she writes:

“If women feel deeply that turning down a promotion that would involve more travel, for instance, is the right thing to do, then they will continue to do that. Ultimately, it is society that must change, coming to value choices to put family ahead of work just as much as those to put work ahead of family. If we really valued those choices, we would value the people who make them; if we valued the people who make them, we would do everything possible to hire and retain them; if we did everything possible to allow them to combine work and family equally over time, then the choices would get a lot easier.”

As I mentioned in my last post, graduate student mothers are told to hide the fact that they are mothers when going on the job market. As if being a parent is a liability. Academia needs to find a way to better bring together work and family.

Before we move on, though, why don’t we all enjoy a puppy picture?

Ahhhhhh.

Now I’d like to discuss some of the feedback I collected through my survey. First, a quick note on this survey. Although I did obtain IRB approval in order to conduct this survey and share the results publicly, I quickly discovered that I had no idea how to design a survey. I had an especially difficult time crafting multi-part questions. For example, I wanted to know how many of my respondents (which included tenure track faculty, fixed term faculty, independent scholars, and graduate students) were offered the option to stop their tenure clock after the birth of a child, who took that option and why. The data that resulted from my questions is confusing since the question was targeted only at those people on the tenure track, followed by those who had the option to stop the clock, followed by those who actually took that option. But I did get some useful data. In partIcular, I was intrigued by the responses to my question “What is your definition of a child friendly department?” I read through all of the responses and was able to sort these responses into 5 broad categories, which I will list below (along with some representative responses).

How Do Your Colleagues Define a “Child Friendly” Department?

1. Openness and Acceptance

“I would define it as a place where children are accepted and discussed as a normal thing, where I don’t have to feel like I might be looked down upon for having children, where I can speak freely about them without reservation. You know, like you’d talk about your dogs. No one is worried that they shouldn’t mention owning dogs because they might be judged or it might affect their academic work. Yet I feel like it’s easier to talk about pets than children.”

“Faculty, staff and graduate students would also not feel uncomfortable even *mentioning* children, which can happen among academics.”

“…parents feel comfortable revealing work/family conflict to chair in an effort to resolve them If possible”

“A department that accepts parenting as an appropriate activity for a professor and makes reasonable accommodations for it.”

“One that understands and accomodates faculty with children such that within reason, parents are allowed to be the kind of parents they would like to be. “

2. Flexibility… for Everyone, not Just Parents

“Rather than child friendly, perhaps family friendly or life friendly–a place which recognizes that humans have obligations to other humans that sometimes interrupt the ordinarily scheduled activities of a career. That said, I do think all department members should be thoughtful and respectful of their colleagues, recognizing that obligations come in lots of shapes and sizes–some of which are easier to talk about than others.”

“A department that recognizes that faculty AND staff are humans with human needs and issues including the care of children [and/or ill family members or elderly parents] with willingness to flexibly schedule committee meetings or to understand the need for occasional help arranging coverage of classes in emergencies (as with conferences and other professional demands) and to offer suggestions for newcomers on how to find effective childcare.”

“A ‘child friendly’ department alternates the times at which meetings and events (readings, workshops, etc.) are scheduled, so that not *everything* happens during a parent’s ‘second shift’ at home.”

“One that understands not to schedule events after 4:30 in the afternoon. One that understands that if you do schedule a lot of nightly events, then you won’t go. And one that makes public statements supporting why parents with young children are less able to participate in extracurricular events.”

3. Where Parents Aren’t Penalized for Being Parents

“A child friendly department is one that …promotes/recognizes employees based on their JOB performance, and doesn’t penalize or overlook employees based on their maternal obligations.”

“…a general respect for my decision to have children, where it is not looked at as a problem, or a road block on my tenure track.”

“A department that doesn’t force people to choose between a career and a family.”

“One that makes it easy for me to be an academic and a parent at the same time. As a grad student, I can’t afford day care, and I live away from my family, which means that since I have the more flexible schedule between me and my non-academic partner, I am the full-time caretake of my kids, as well as a full-time student, part-time teacher, union steward, committee member, etc. I don’t have the luxury of separating these out.”

“Provides parents with the same opportunities as non-parents. Does not give parents or non-parents an advantage over each other.”

4. Clearly Defined (& Fair) Parental Leave Policies, Including the Option to Stop Tenure Clock

“Gives teaching and graduate assistants maternity leave…”

“A department that provides parental leaves for both partners and in the case of a single parent a longer leave or reduced load including the leave. In addition, if a faculty member elects to stop the tenure clock then at the time of assessment one should not look at when s/he received his/her Ph.D.”

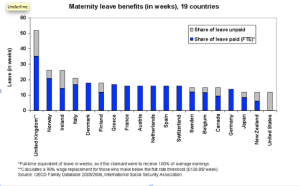

In “Why Maternity Leave is Important,” Meredith Melnick cites a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) that found: “Women with 3-month-old infants who worked full time reported feeling greater rates of depression, stress, poor health and overall family stress than mothers who were able to stay home (either because they didn’t have a job or because they were on maternity leave).” These results suggest that the transition back into employment immediately after childbirth is difficult for the average family. Mothers in particular get stressed and depressed when they must return to work too soon after the birth or adoption of a child. And a stressed/depressed mother has a negative impact on her children. Melnick quotes NBER researchers, Pinka Chatterji, Sara Markowitz and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, who found that “Numerous studies show that clinical depression in mothers as well as self-reported depressive symptoms, anxiety, and psychological distress, are important risk factors for adverse emotional and cognitive outcomes in their children, particularly during the first few years of life.” Despite the results of studies that demonstrate the necessity of some kind of paid parental leave for new parents, the U.S. is one of two developed economies in the world that do not provide some form of universal paid maternity leave (the other is Australia). This is the same country that produces senators like Rep. Todd Akin, the Republican nominee for Senate in Missouri, who believes the female body contains “biological defenses” that prevent it from getting pregnant during a “legitimate rape.” In other words, women shouldn’t abort their babies and they can’t take off work to care for them either. But I digress…

In terms of the folks I surveyed, 23% took an unpaid parental leave, 32% took a paid leave and 28% took no kind of leave after the birth/adoption of a child. Of those who did not take any time off, 15% said their departments did not offer paid leave, 9% worried it would affect their ability to keep their jobs, 6% worried it would impact their ability to get tenure, 12% (who were men) said that men do not normally take leave in their departments and 9% said they didn’t take leave because they didn’t want to. In general, it seems that the length of parental leaves (if they are offered at all) vary wildly from school to school. I was lucky to get a paid maternity leave of one full semester after the birth of my son. Since he was born, my university’s policy has been shortened from a full semester (15 weeks) to 12 weeks. I don’t see how this change saves the university much money (do we save money by having a professor teach 4 weeks of a 15 week course?) and since I am currently on my university’s Faculty Welfare Committee, I plan to address this change when we meet again this fall.

5. Your Question is Illogical!

4 of my 180 respondents responded to the question “How do you define a child friendly department” with something along the lines of “Girl, you crazy!”

“Why do we need a definition? An employee’s job is to work. Their outside responsibilities belong outside of the work environment. University employees are employees just like in a business. Business does not allow exceptions for parents with children-schedules or maternity leaves. Only in this environment would the employees be pandered to in this way.”

“I don’t have one. Why would other adults do favors for my children? My colleagues interact with me and I am not a child.”

“One of the problems to be considered when exploring the idea of ‘child friendly’ is a perceived disconnect between faculty expectations and the ‘real-world’ workplace. To put this another way, the public is unlikely to be supportive of expressions of concern about the absence of a child friendly culture when they have to do without it in their lives. Nor is the legislature likely to be supportive.”

These comments are not representative of the vast pool of responses I received, but I found them worth reporting because they address something important that academics need to consider: do we expect too much? After all, a parent working in a top law firm can’t expect meetings to be scheduled around her daycare schedule and an ER doctor can’t refuse to work nights because he wants to be able to put his baby to bed.

Bonnie J. Dow argues that lack of institutional support for colleagues with children ends up hurting the entire department: “…as long as family-friendly departments enable academic parents to rely on their colleagues’ informal support, they simultaneously enable institutions to forestall developing the structural solutions that would make that support less necessary.” She claims that when a faculty member agrees to cover a class after a colleague gives birth “…the unintended consequence of such short-term fixes is that institutions continue to rely upon them as ad hoc and interpersonal solutions to a structural problem.” Likewise, academic parents must be careful not to take advantage of colleagues. Dow offers 5 rules that academic parents should follow in a good faith effort to not take advantage of their child-free colleagues:

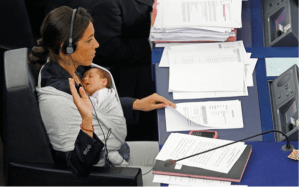

1. Don’t bring kids to the office

2. Don’t bring kids to meetings

3. Arrange for child care for meetings (NOT JUST TEACHING)

4. Department couples are not interchangeable—you both need to be present

5. Colleagues are not required to accommodate your parenting philosophy

I’m not sure that I agree with all of Dow’s suggestions. If your child is ill and you must get to campus to meet with a student, you might have to bring your kid with you, and that doesn’t seem like it should be a big deal. But Dow’s overarching point seems to be: remember that you are part of a department. Meetings, job candidate dinners, and the like, are all part of your work obligations and you should therefore have childcare available for those events. When you stop pulling your weight, your weight doesn’t vanish. It just appears in someone else’s “to do” pile. Colleagues should keep my precarious schedule in mind (if you want me to attend a weekly meeting, then try to schedule it during my kid’s day care hours) but my needs do not trump their needs. At some point every member of a given department is going to have a personal situation conflict with duties at work. As colleagues we need to be able to take up each other’s slack when needed and within reason.

How can we do this? Jason Mittell offered some great suggestions during our worksop. As chair of his department he has instituted and/or supported the following policies to make life easier for the humans who work there (and the humans who depend on them) :

* Make kids visible. By acknowledging that we’re parents & not trying to hide it in the workplace, we all can be more sensitive to various demands & conflicts that can emerge. This means both talking about our kids and making a welcome environment for them to be in the office when necessary.

* Fewer meetings. Whenever possible, we try to deal with things via email or ad-hoc rather than have frequent regular meetings, recognizing that the more flexible our schedules are, the better. Not all faculty members feel this is preferable, but to me, at least, it helps ensure that time spent in the office is more focused on what I need it to be, rather than the formalities of meetings.

* Sensitive scheduling of meetings. When we do have meetings, we try to schedule them during regular hours that coincide with school/daycare coverage (i.e. never later than 4:30, ideally on Friday afternoon or other times when nobody teaches).

* Sensitive scheduling of class times. For faculty with kids, we try to let them schedule the timing that works best for them. This includes screenings, which we allow to be scheduled concurrently to allow us to only be out one night each week.

* No “face time” expectations. For some faculty, there is frequently a culture of “face time,” where being around the office is an expectation & you’re judged by your presence. I’ve tried to push back against this, emphasizing that as long as you’re getting your work done & students/colleagues know how to get in touch with you, it doesn’t matter where you’re doing it. For staff, it’s a bit more complicated (and I’d love to hear ways to make things work better in this regard), but in general I hope that people feel our department is one where being away from your desk isn’t seen as a problem.

* Embrace flextime & telecommuting. When kids are sick, have events or appointments, or otherwise draw you away from the office, it’s not a big deal to work from home or shift your normal hours around, as long as students & colleagues who need to know are in the loop.

* Engage the conversation. When I shared this list with my colleagues, half of them expressed their appreciation that I had raised the issue. As one said, “I knew that the department embraced these ideas, but having them spelled out in an email from the chair makes it feel more validated and legitimate.”

Don’t you all wish Jason was your department chair?

*****

In the comments section I would love for readers to share their experiences — both good and bad — with being a post-grad academic parent. What policies have been the most helpful to you and why? What changes were you able to make to your department or university’s policies regarding parental leave, the tenure clock, on-site daycare centers, and/or scheduling needs? What changes were you unable to make? And for those academics without children — how have colleagues with children impacted your work life? How have you tried to accomodate them and, just as important, how have they tried to accomodate you? Keep in mind that if you feel uncomfortable having this conversation in a public forum (these are sensitive issues), you can feel free to use an alias. I won’t out you.

Works Cited

Dow, Bonnie J. “Does it Take a Department to Raise a Child?” Women’s Studies in Communication 31.2 (2008): 158-165.

Melnick, Meredith. “Study: Why Maternity Leave is Important.” Time 21 July 2011. <http://healthland.time.com/2011/07/21/study-why-maternity-leave-is-important/>.

Slaughter, Anne-Marie. “Why Women Still Can’t Have it All.” The Atlantic July/August 2012. <http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/07/why-women-still-cant-have-it-all/309020/>.

Townsley, Nikki C. & Kristin J. Broadfoot. “Care, Career, and Academe: Heeding the Calls of a New Professoriate.” Women’s Studies in Communication 31.2 (2008): 133-143.

Work, Study and Scholarship as an Academic Parent, Part I: Grad School Babies

On July 19-21 I attended the biennial conference, Console-ing Passions: A Conference on Television, Audio, Video, New Media, and Feminism, hosted by Suffolk University (on a side note, if you write about or study anything related to these themes, I strongly encourage you to apply to Console-ing Passions in 2o14. You won’t regret it). In addition to presenting a paper on Teen Mom (don’t you judge me), I also chaired a workshop entitled “Work, Study and Scholarship as an Academic Parent.” During this workshop, Eleanor Patterson, Jason Mittell, and Melissa Click, three media studies scholars at different points in their academic careers, candidly discussed the challenges and rewards, both personal and professional, related to being a parent in academia.

The reason I’m sharing what transpired during this workshop here is twofold. First, as anyone who has ever attended an academic conference knows, the turn out at individual panels and workshops is precarious. You could have 50 people in your audience or 5 (we had more than 5, less than 50). I thought the stories and advice that circulated during our 90-minute workshop would be useful reading for other parents who live and work in the Ivory Tower as well as those who are pondering whether or not to become parents. Second, for my part of the workshop I explored definitions of the “child friendly department” — and what academics with children have a right to expect (or not expect) from their employers, colleagues, and students — and conducted a survey to see how other folks in the academy defined this term. I am grateful that 180 busy parents agreed to participate in my survey. Since many of them told me they were curious about its findings, I wanted share the results here.

I will cover the workshop in two parts to make reading and sharing more manageable. In Part I I will be discussing the challenges and rewards of having a child while still in graduate school and in Part II I will address the challenges and rewards of post-doc life with children.

“Navigating Motherhood as a Media Studies Graduate Student”

During our workshop Eleanor Patterson, a doctoral student in the Media & Cultural Studies program at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, discussed her experiences being a parent while still in graduate school. I asked Eleanor if she would participate in this workshop after reading her smart, funny, and insightful post, “So You Want to be a Grad Student Mama.” Here are some (but not all) of the key points Eleanor addressed during our workshop, with additional commentary by me (because I just can’t help sharing my own war stories):

Parenting is a feminist issue

Eleanor began her presentation with this statement: “being a parent in academia is a site where power is literally exercised over the body, in how we reproduce and parent. As a grad student, our labor has less political and social power within academic institutions.” It is difficult to be a new parent in any context but when you become a new parent as a graduate student, the low man/woman on the academic totem pole, navigating the field becomes even more difficult. New parents often find themselves in situations where they must request “special considerations” (flexible scheduling, missing meetings to care for sick children, etc.) and asking for these considerations is daunting when you feel like you have no power or that the very act of asking could somehow tarnish your reputation as a “serious” scholar. You become paranoid, constantly wondering how your choice to have a child will impact how others see you. You become extra determined to not let being a parent impact the way you function professionally (which is impossible, by the way).

As the authors of “Making Space for Graduate Student Parents: Practice and Politics” point out, being a parent and being an academic are similar in many ways: “The intensity and reverence with which academics and parents undertake their respective ‘labors of love’ is undoubtedly similar. And certainly both vocations can be marked by constant self scrutiny and a nagging sense of incompletion and imperfection.” It’s true. Nevertheless…

Being a parent and a graduate student are two roles that frequently appear to be at odds

During our workshop, Eleanor rightly pointed out that unlike faculty parents, grad students must adjust to “the new demands of academia while simultaneously adjusting to the new life of parent.” Although very little research has been done on graduate student parents, what is known is that there is a lower attrition rate for graduate student moms. After citing this fact, Eleanor was quick to add “I don’t mean to suggest that grad students shouldn’t be moms, but I bring this up to say that being a grad parent is complicated and there are concrete, material incongruences with how academia is structured and being a grad parent.” To name just one example, graduate students often struggle financially as they are sandwiched between student loans stemming from college and a highly uncertain economic future. And new babies? Well, they cost a lot of money. They need clothing and diapers and constant visits to the doctor and toys that are made with lead-free paint. How can a grad student, who can barely pay her rent, support the life of another human being?

It should not be surprising then that the majority of graduate students decide to wait until after they finish their degrees, or later, to have children. According to Mary Ann Mason’s 2009 article in The Chronicle of Higher Education “Exact figures are elusive, but a study we did of doctoral students at the University of California indicated that about 13 percent become parents by the time they graduate.” This is a problem for female academics in particular since the median age for women to complete a doctoral degree is 33 and for most women, fertility begins to drop starting at age 30. In her aforementioned blog post on parenting as a grad student, Eleanor explains “I also believe that the general discourse that encourages women who want children to wait until they’ve completed their Ph.D. is part of a greater patriarchal discourse that disciplines our bodies. I think it is similar in many ways to the advice female faculty often receive to have their children over the summer. As if taming our biological reproduction to match the academic school calendar would make academia more amenable to parenting or mothering.”

After my husband and I got together in my early twenties, we began to have earnest conversations about when we could start having children. I was emotionally ready for kids, but I was terrified about how it would impact my academic career. How would I finish my degree with a child in the house? Would I ever get a job if I had a kid first? I asked some of the professors and older graduate students in my department for advice and received lots of conflicting opinions. One popular answer was to wait to start my family until I was awarded tenure. Allow me to explain why this is problematic logic: I started my Masters degree in the Fall of 1999 and finished my PhD in the summer of 2007. Other than taking one year off after my MA to work for AmeriCorps so that I didn’t start drawing symbols and formulas all over the windows of my Pittsburgh apartment, Beautiful Mind-style (a story for another time, perhaps), I moved relatively quickly through my degrees. Then I won the academic lottery by snagging a tenure track job for the fall of 2007. If all goes well and I am awarded tenure in the spring of 2013 (fingers crossed), I will be 36 years old.

If I had waited to have children until tenure, I would be trying for my first at age 36. I know many women who were able to get pregnant with healthy babies at age 36 and beyond. But I also know a lot of women my age and older who are suffering through the stress and financial burden (not to mention the heartache) of infertility. Simply put, it is more difficult (and expensive) to get pregnant in your mid-30s. So, for many female academics who want to start a family, having a child while still in graduate school is probably the only way to do both. As Mason points out “[Many women] can see their biological clocks running out before they achieve the golden ring of tenure.”

Grad students are urged to “hide” their pregnancies and/or babies when they go on the job market

Eleanor explains that “Graduate student mothers are not only confronted with logistical difficulties, limited support, and potentially constrained career paths; they must also contend with conflicting and powerful ideologies that surround academia and motherhood. I know this is an issue, because every professionalization workshop on job talks, and being on the job market, have emphasized that you should not discuss your position as a parent, or your partner, at all, unless once you have an offer, you might angle for a spousal hire.” I was given the same advice when I went on the academic job market in the winter of 2006. At the time, I was still breastfeeding my 7 month-old daughter, so keeping my status as a parent under wraps was challenging. Breast feeding mothers who are away from their babies need to pump every few hours or else they risk diminishing or losing their milk supply.

During my campus interviews I had to ask for a bathroom break every few hours so I could hide in a stall and pump, praying that no one would inquire about the weird “whoosh whoosh” sound of my battery-powered pump. I would emerge from the bathroom 20 minutes later, with a wrinkled suit and sweaty brow, pretending like nothing unusual had just occurred. When I finally gave up this exhausting ruse and told one of my future colleagues what I was up to (this was my third campus interview in the space of 2 weeks and I was just fed up with lying), he breathed a sigh of relief and said “Oh great, I’m glad you told me you have a kid. Now I can tell you about child friendly our department is!” How silly I felt for keeping it a secret. I’m not saying that all of you parents should out yourself during your job interviews this fall but a good question to ask yourself is this: do you want to spend the next 40 years working in a department that sees your children as a liability?

Grad students are inadvertently penalized for having kids

Part of being a graduate student is immersing yourself in your field. In addition to taking classes, teaching classes and writing, graduate students benefit from attending talks given by guest speakers, participating in colloquia, and (if you are a film studies scholar like myself), going to (or renting) movies with your fellow students. But when you are a parent, your time becomes limited. Once you have shelled out money to cover daycare while you go to class, teach and write, you are unlikely to have additional funds for a sitter so you can go to a talk, much less a movie. While your friends are having cocktails with Dr. Famous Scholar after her amazing, intellectually stimulating talk, you’re at home stacking blocks with your baby. Yes, your baby is wonderful, but you are definitely missing out on some key grad student experiences.

During her presentation Eleanor cited a study by the American Sociological Association that found that many crucial resources — including help with publishing, mentoring, effective teaching training, and fellowships — were less available to graduate student parents, particularly mothers, than to other students (Spalter-Roth & Kennelly, 2004). Graduate mothers are also less likely to be enrolled in higher ranking departments (Kennelly & Spalter-Roth, 2006). Furthermore, having a child in graduate school often comes with little to no support. Mason found that “Only 13 percent of institutions in the Association of American Universities (the 62 top-tanked research universities) offer paid maternity leave to doctoral students, and only 5 percent provide dependent health care for a child.”

What to do if you want to have a child while in graduate school:

Unless you have had a Doogie Howser-like educational trajectory and thus finished your Ph.D. in your mid-twenties, having a child while still in grad school may be the only option for women (and men) who want both an academic career and a family. Eleanor offered up some great questions to ask yourself before you make the decision to have a child while finishing up your graduate degree:

*How much university/departmental support is available for graduate students with children?

*Will you get paid parental leave and/or continuation of health insurance when you take parental leave?

*Will your health insurance cover dependents?

*Will your department “stop the clock” on your funding while you take parental leave?

*Is there an on-campus daycare (or any daycare) that you can afford?

*Are professors in your department willing to give you some leeway (in terms of paper extensions, missed classes, etc) after your child is born?

*How far along are you in your degree? The final years of dissertation work are often the most conducive to parenting since you no longer need to be on campus daily for classes.

Saranna Thornton outlines similar ways to make parenting more amenable to graduate students here.

It’s still hard

Finishing a Ph.D. is hard. Raising a child is hard. Putting those two jobs together? Very, very hard. Eleanor offers some of the highlights “To get things turned in on time, I have to plan my weeks out in advance, and no longer have the luxury of waiting for my muse to hit before I begin writing. I regularly have to write during my ‘free’ time between class/teaching to get stuff finished.” She also describes typing papers with a sleeping child on her lap. I have clear memories of breastfeeding my newborn daughter while simultaneously typing up my job application letters. I’m not sure that I would ever want to relive the year in which I had my first baby, completed my dissertation, taught two classes, and applied to 40 jobs. But what kept me going that year (and what continues to keep me going) is the realization that the pay off for all of that stress, the many sleepless nights, and endless hustle to write during the isolated gaps of my day (being a parent teaches you how to write any time), is a job that makes me happy when I am away from my children and a personal life that makes me happy when I am away from my job.

Of course, I should add that I had an ideal situation for having a baby during graduate school. My husband worked from home and made a good salary so that we could afford to hire a nanny for 25 hours each week. This gave me just enough time to finish my dissertation and apply to jobs (even though I still did a lot of this work while holding a baby in my lap). But even if you don’t have a partner with a great job, here are some reasons why having a child during graduate school can be a great choice:

* your schedule is far more flexible as a graduate student (especially an ABD) than it is as a full-time faculty member (remember a TT job involves research, teaching, service, and meetingsmeetingsmeetings)

* when things get crazy in the first years of the job, your child will be older and less likely to be keeping you up all night with his/her blood-curdling screams

*since most of your graduate student cohorts don’t have (and don’t plan to have) kids, you will have a built-in community of eager aunties and uncles who will genuinely enjoy taking a break from “the life of the mind” to play with your kid for a few hours while you work on dissertation revisions (or at least, this was my experience)

*the push to publish a book (or two) once you are on the tenure track often scares faculty away from having kids. I know several academics who fully intended to have children before landing their first job and who now say “Who has the time?”

I hope this section doesn’t come off as “this worked for me so it must work for everyone” advice. My point is that graduate students are often under the impression that they must put having children on hold until they finish their degrees or get tenure. I don’t think this is necessarily the best advice.

Embrace your choice

As Eleanor concluded her presentation she offered up a great piece of advice to graduate student parents: “perform legitimacy.” In other words, don’t apologize for your decision to have a child or hide this fact. The more visible student parents are, the better the environment will be for all graduate student parents. She also emphasized the importance of good mentors, both at the graduate student and at the faculty level.

I mentioned earlier in this piece that as a graduate student I was advised by many to wait until tenure to have children. However, I had one faculty mentor who gave me very different advice. She was one of the few professors in my department who brought her child to receptions and events and discussed the fact that she was a mother openly. As a graduate student I watched her do this and I mentally noted: “This is possible. This is okay.” One day I asked her to meet me for coffee and she told me about her experiences having a child in graduate school and why it was a great decision for her. I view this conversation as one of the most pivotal in my entire academic career and I will forever be grateful to this mentor. I hope to do the same for someone else some day.

*****

This post, as well as Eleanor’s workshop presentation, are based almost entirely on personal experiences. I would love for readers to share their experiences below. What kind of advice (if any) did you receive about having children in graduate school? If you ended up having kids as a student, what was the biggest challenge and the biggest benefit of this decision? What advice would you give to graduate students who are contemplating having kids right now? Although this post focused more on the experiences of female graduate student parents, it would be great to hear from all of the men out there who had children while in graduate school (we know it’s hard for you guys too). How did your experiences differ from those outlined in this post?

Works Cited (& further reading)

Collett, Jessica. “Navigating Graduate School as a (Single) Parent.” scatterplot 5 Apr 2010. <http://scatter.wordpress.com/2010/04/05/navigating-graduate-school-as-a-single-parent/>.

Kennelly, Ivy and Roberta M. Spalter-Roth. “Parents on the Job Market: Resources and Strategies that Help Sociologists Attain Tenure-Track Jobs.” The American Sociologist 37.4 (2006): 29-49.

Mason, Mary Ann. “Why So Few Doctoral-Student Parents?” The Chronicle of Higher Education. 21 Oct 2009. <http://chronicle.com/article/Why-So-Few-Doctoral-Student/48872/>.

Patterson, Eleanor. “So You Want to be a Grad Student Mama.” Antenna 2 Aug 2011. <http://blog.commarts.wisc.edu/2011/08/02/grad-student-mama/>.

Springer, Kristen W., Brenda K. Parker and Catherine Leviten-Reid. “Making Space for Graduate Student Parents: Practice and Politics.” Journal of Family Issues 30.4 (2009): 435-457.

Thornton, Saranna. “Faculty Forum: Making Graduate School More Parent Friendly.” Academe Online Nov 2005. <http://www.aaup.org/AAUP/pubsres/academe/2005/ND/Col/ff.htm>.

Me and My Twitter: Our Untold Love Story

This week I taught the film Wall*E (2008, Andrew Stanton ) in my Film Theory and Criticism course. I selected the film to complement the week’s topic on digital cinema. However, my students were far more interested in discussing the film’s post-apocalyptic vision of an Earth so overrun with consumer waste that it must be abandoned for a clean, automated, and digitized existence on the Axiom, a spaceship that caters to humankind’s every need. Robots take care of human locomotion (which is why these humans are no longer able to walk), food (lunch in a cup!), grooming (robot manicurists!) , and even decision-making:

My students were critical of these human characters: for their sloth, their apathy, and most importantly, because of their inability to form real human connections. “They only communicate with each other through screens!” they lamented. I then pointed out that the behaviors of the humans on the Axiom are not too different from the behaviors of the humans on our college campus. As I walk to and from my office I see students, heads bent, eyes averted, typing away on their smart phones. Those who aren’t typing on their phones are talking on their cell phones or listening to their I Pods. Eyes plugged, ears plugged, the students I see each day rarely commune with the real world around them. Like the humans on the Axiom, we are surrounded by screens and by virtual relationships. This realization seemed to depress my students.

But I’m not all that saddened by this vision of the future. No, I don’t want to become a rotund, infant-like drone, sucking my lunch out of a cup, but I am quite fond of the connectivity fostered by the internet and the proliferation of increasingly more affordable smart phones. In particular, I love Twitter. Man, do I love Twitter.

When I first joined Twitter in March 2009, I found it to be a lonely place. Gone were the hundreds of friendships I had accumulated on Facebook. Gone were those cute pictures of people’s babies and dogs (no really, I like seeing those). Gone was the instant validation I received when friends commented on my witty and hilarious status updates with their witty and hilarious rebuttals. Instead, I was faced with a long lists of 140 character statements, typed up by strangers, and addressed to no one in particular.

But over time I grew to understand the role of Twitter in my life. As many people have pointed out, Facebook is for connecting with the people I already know. Twitter, however, is for connecting with the people I would like to know. Sound creepy? Sure it does. But really it makes a lot of sense.

In my profession (higher education), networking with colleagues is key. In the past, such networking took place mostly at academic conferences. For example, imagine you are the editor of a film studies journal and you hear someone deliver a paper that sounds perfect for your next issue. You might approach the speaker at the end of the panel and ask her if she’d consider submitting her conference paper for publication in your journal. Or imagine you’re a graduate student and you need to find a scholar outside of your university to serve as a reader of your dissertation. You can approach one of your academic heroes at the bar later that evening, introduce yourself, and pop the question.

Yes, that’s all fine and good for the extroverts among us. But me, I’m an introvert. Or rather, I am the worst kind of introvert — an extroverted introvert. In other words, I love to socialize and meet new people, but I hate being the one who initiates the socializing and I hate introducing myself to new people. I don’t make a great first impression, but I make an excellent third impression. So up until the advent of Twitter, I was not able to meet many new people or forge important professional connections when I attended conferences. Instead, I mostly hung out with my (admittedly awesome) friends from graduate school, getting very drunk in the hotel bar.

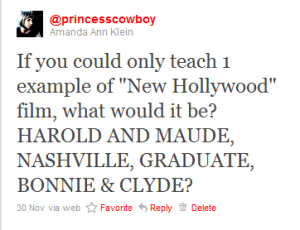

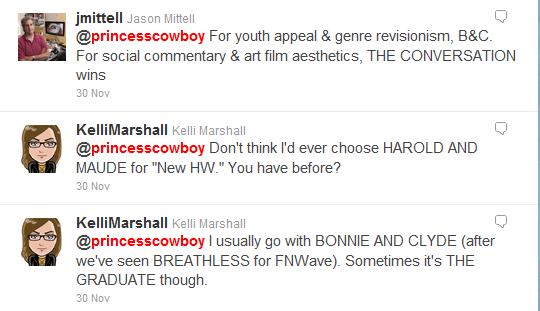

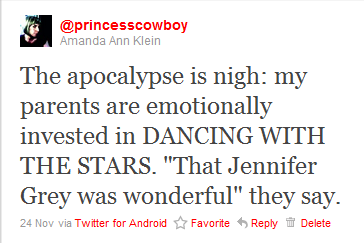

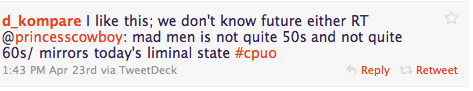

But all of this has changed because of Twitter. Not only has it allowed me to meet with loads of new and interesting film and media scholars at conferences, it has also allowed me to develop professional relationships with people I have yet to meet. Many of the people I follow on Twitter also teach film and media studies courses and, even though we have not personally met, are more than willing to offer advice. For example, I am currently developing a syllabus for a new course, American and International Film History (1945 to the Present) and was having a hard time selecting a film for my week on New Hollywood Cinema. What to choose? So, I posed to the question to the Twitterverse:

And here are some of the responses I received:

This kind of conversation is especially important for someone like me, who teaches at a university in which there are only a few film studies scholars (there are three of us to be exact). Twitter provides me with an opportunity to brainstorm syllabus ideas, to get research suggestions for upcoming projects, and even to receive feedback on works in progress (via this blog) with an unlimited, virtual community of colleagues. It’s pretty amazing when you think about it.

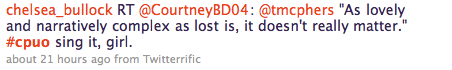

Another thing that I love about Twitter is that it assembles an ever-present virtual community who is willing to listen, or at least bear witness to, my daily grievances. Here’s a post from a few weeks ago:

There is nothing profound about this tweet. In fact, it’s the kind of banal statement that most people would cite as evidence of Twitter’s utter pointlessness. But when I wrote this, I was having a bad day. And the shoes that I had to wear during my long walk home in the rain were destroyed. So it felt good to send my annoyance out there into the Twitterverse. Even if no one read it, the Tweet exists, and that’s enough for me.

Twitter is also great for someone in my profession because much of my work is completed in solitude. Yes, I teach in front of large groups of students and yes I have to attend committee and department meetings, but by and large I work alone. Therefore, Twitter affords me the opportunity to drop in and out of ongoing conversations, to comment on someone else’s tweet, to read a recommended article, or to watch a clip of someone crying about a “double rainbow,” when the mood strikes.A few minutes here, a few minutes there. It’s just the break I need in order to remain productive and, oddly enough, focused on the task at hand. Twitter is like a virtual coffee house filled with hundreds of interesting, funny, and bizarre individuals, who can be tuned in or tuned out throughout the course of the day.

It’s true, Twitter has caused me to share more banal details about my life than Facebook ever did:

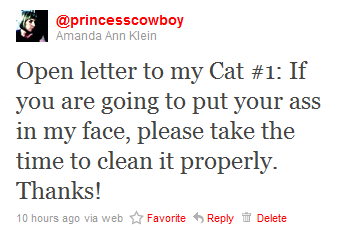

And no one really needed to know that my cat doesn’t clean his ass after he uses the litter box:

Nevertheless, Twitter has added real value to my life. When I got my very own smart phone almost two months ago, I joined the other screen-entranced zombies who shamble across the ECU campus. But it’s not so much that I’m tuning the real world out. I like to think that I’m bringing more of the world in.

If you’re interested in reading more about the impact of being “plugged in,” you may be interested in the much-discussed (at least in the Twitterverse) article by Virginia Heffernen, “The Attention-Span Myth,” as well as Michael Newman’s thoughts on her piece. Both were written with more time and care than this blog post. But that’s because I’m too busy tweeting, ya’ll.

BADLANDS: The Film I Always Find a Way to Teach

Whenever I meet new people and they discover that I teach film for a living, they invariably ask me: “So what’s your favorite movie?” I realize that this is polite, small talk kind of question. It’s the kind of question people think that they are supposed to ask me. But to someone who has devoted their livelihood to researching, analyzing, and teaching about moving images, the question is agonizing. Asking me what my favorite movie is is like asking me: “Which of your children do you love the most?” There is simply no way for me to answer this question in a satisfying, honest way. So I usually tap dance around the answer, trying all the while to not sound like a pretentious academic douchebag (which is what I am). “Oh it’s so hard for me to choose!” I say. When the asker looks sufficiently annoyed, I usually submit and say something expected like “Casablanca. Casablanca is my favorite movie” Then they leave me alone.

But the real answer to the question “What is your favorite movie?” is very complex for me. I love different movies for different reasons. I love Double Indemnity (1944, Billy Wilder) for its whipsmart, sexy dialogue. I love The Crowd (1928, King Vidor) for its winsome, bittersweet ending. I love Magnolia (1999, Paul Thomas Anderson) because it was the only movie to figure out the exact kind of role that Tom Cruise should play. I love The Breakfast Club (1985, John Hughes) because I watched it pretty much every Saturday afternoon on TBS when I was 12 and didn’t realize that they weren’t smoking cigarettes during that one scene in the library. I love American Movie for so many reasons but especially because of this scene:

And I love Terence Malick’s debut film (his DEBUT!), Badlands (1973), because it is, for lack of a better word, a perfect movie. Badlands is a movie that I never tire of watching. I get giddy about the opportunity to introduce it to new people. For that reason, I try to put Badlands on my syllabus whenever possible. In fact, this week I screened Badlands for my Film Theory and Criticism students for our unit on film sound. I love teaching this film because, as I mentioned, it’s perfect, and most students have not heard of it. Therefore, after the screening students generally exit the classroom with the same dazed, but happy, expression I had after I watched it for the first time.

So what makes Badlands a “perfect” movie?

Terence Malick’s Script

In the very first scene of the movie we see Holly, a 15-year-old girl (Spacek was 24 when she played the role) with red hair, freckles, and knobby knees. She is playing with her dog on her bed. It is a scene of innocence, of total girlhood joy. But this happy, carefree image contrasts with Holly’s vacant, flat, voice over, which informs us “My mother died of pneumonia when I was just a kid. My father kept their wedding cake in the freezer for ten whole years. After the funeral he gave it to the yard man. He tried to act cheerful but he could never be consoled by the little stranger he found in his house.” In four brief lines Holly aptly summarizes her childhood: she was an only child; her father was once a real romantic (he kept his wedding cake in the freezer for 10 years after all) but the untimely death of his wife deadened his heart (he gave the cake to the yard man after his wife’s funeral); Holly and her father are unable to connect emotionally (Holly knows that her father sees her as a “stranger”). Such is the mastery of Malick’s tight script — not a word is wasted.

Malick’s script is also admirable in that he was able to capture the rhythm and the texture of a teenage girl’s stream of consciousness. Holly doesn’t speak like an adult and she doesn’t speak like a child. After Kit kills Holly’s father he instructs her to grab her schoolbooks from her locker so that she won’t fall behind in her studies. Holly’s voice over then tells us “I could of snuck out the back or hid in the boiler room, I suppose, but I sensed that my destiny now lay with Kit, for better or for worse, and it was better to spend a week with one who loved me for what I was than years of loneliness.” If these words were in Holly’s diary they would probably be adorned with hearts over the i’s and little flowers scribbled in the margins.

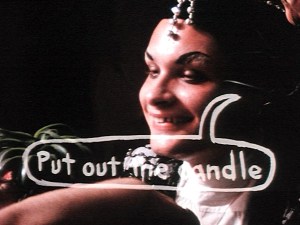

Holly’s Voice Over/The Stereopticon Scene

There are so many scenes I could point to that illustrate the genius of Sissy Spacek’s line readings in this film, but my favorite is the much-lauded stereopticon scene. After killing Holly’s father the couple flees to the woods and build themselves a Swiss Family Robinson-style tree house (though it is likely that the grandure of this house has been imagined by Holly). In the middle of this segment, Holly sits down to look at some “vistas” in her father’s stereopticon. This is the first time that Holly has mentioned her father since his murder and yet she still does not mention if his death bothers her. As Holly looks at travelogue images of Egypt and sepia-toned lovers, she waxes philosophical, in the self-involved way that only a 15-year-old girl can. As she looks at an image of a soldier kissing a morose young woman she wonders “What’s the man I’ll marry look like? What’s he doin’ right this minute? Is he thinking about me now by some coincidence, even though he doesn’t know me?” As the camera slowly zooms in on this particular image Holly asks, the excitement barely rising in her quiet voice “Does it show in his face?”” The non-diegetic music becomes more intense as the scene progresses. Holly is coming to an epiphany. She is just some girl, born in Texas, “with only so many years to live.” She is aware that her life is structured by a series of accidents (her mother’s death), and yet, that life is also fated (“What’s the man I’ll marry look like?”). This voice over indicates that Holly is able to see her role in the larger web of humanity, and yet, this same girl watches as her boyfriend shoots her father and random unfortunates who happen to cross their path. It is infuriating and chilling. In fact, every time I watch this scene I get chills.

Kit/ Martin Sheen