Television

Call for Papers: Multiplicities: Cycles, Sequels, Remakes and Reboots in Film & Television

I wanted to use this space to promote an anthology I will be putting together with R. Barton Palmer, a wonderful scholar and colleague who I met back in the Spring of 2011, when he gave talk at ECU. If you are reading this post (Hello, YOU!) and you know of anyone who might like to submit an abstract (due August 30, 2012), please pass along the information below.

Multiplicities: Cycles, Sequels, Remakes and Reboots in Film & Television (working title)

Project Overview:

Like film genres, film cycles are a series of films associated with each other due to shared images, characters, settings, plots, or themes. But while film genres are primarily defined by the repetition of key images (their semantics) and themes (their syntax), film cycles are primarily defined by how they are used (their pragmatics). In other words, the formation and longevity of film cycles are a direct result of their immediate financial viability as well as the public discourses circulating around them. And because they are so dependent on audience desires, film cycles are also subject to defined time constraints: most film cycles are financially viable for only five to ten years. The contemporaneity of the film cycle—which is made to capitalize on a trend before audience interest wanes—has contributed to its marginalized status, linking it with “low culture” and the masses.

As a result of their timeliness (as opposed to timelessness), film cycles remain a critically under examined area of inquiry in the field of film and media studies, despite the significant role film cycles have played in the history of American and international film production. This collection of essays seeks to remedy that gap by providing a wide-ranging examination of film cycles, sequels, franchises, remakes and reboots in both American and international cinema. Submissions should investigate the relationship between audience, industry and culture in relation to individual production cycles. We are also soliciting essays that examine how production cycles in the television industry are tied to audience, culture, and production trends in other media.

Possible topics include, but are not limited to:

-sequels, trilogies, and franchises as cycles

-the relationship between film cycles and subcultures

-the relationship between film cycles and political and social movements

-analyses of intrageneric cycles (film cycles within larger film genres) such as teen-targeted musicals (High School Musical, Save the Last Dance, You Got Served) or torture porn horror films (Saw, Hostel, Touristas)

-analyses of intergeneric film cycles (stand-alone film cycles) like disaster films (The Day After Tomorrow, Poseidon, 2012) or mumblecore (Baghead, Cyrus, Tiny Furniture)

-the transmedia nature of cycles (the relationship between Harry Potter books, films, toys, video games, fan fiction, vids, etc.)

-the relationships between cycles in television, music, and film, like the appearance of fairytale television shows (Once Upon a Time, Grimm) and films (Snow White and the Huntsman, Mirror, Mirror) in 2011-2012

-production cycles found within television (television musicals, comedy verite, etc.)

– essays that explore the (dis)connections between film cycles, on the one hand, and remakes, sequels, adaptations, and appropriations on the other

Submission Guidelines:

Please submit your abstracts of 400 words and a brief (1-page) CV via email to both of the editors by August 30, 2012. Finished essays should be approximately 6,000 to 7,000 words in length, including footnotes. Acceptance of essays will be contingent upon the contributors’ ability to deliver an essay that conforms to the work proposed by the submitted abstract. We will notify contributors by November 2012.

Please email your abstract and CV to both editors:

R. Barton Palmer: PPALMER@clemson.edu

Amanda Ann Klein: kleina@ecu.edu

I am also happy to answer any questions you might have about this project over email.

Reconsidering GIRLS

A month ago I participated in a blogathon devoted to the new HBO program Girls. The impetus for the blogathon was a series of discussions I was having with some media studies scholars (primarily Kristen Warner and Jennifer Jones) about the hype leading up to the show’s April 15th premiere. The public discourses surrounding the Girls premiere — in commercials created by HBO, interviews with the press, and reviews by critics who received advanced copies of the first three episodes — primarily stuck to the same theme: Girls is an authentic portrait of what it is like to be a twentysomething female today. Had the show simply been promoted as a new quirky portrait of a pirvileged, highly-educated but emotionally immature young woman’s struggles to make it as an artist in New York City, I am not sure our blogathon would have taken place at all. But the show’s generic title, which implies a universality (even as it mocks the maturity of its protagonists), coupled with the ecstatic reviews lauding the program’s authenticity, bumped up against the program’s rather rigid white, heterosexual, upper-class cast in an unpleasant way. Thus, the blogathon was our attempt to ask: do we take a television series to task for claiming to provide an authentic female bildungsroman when its “authenticity” is limited to one vision of female life?

One thing I did not say in my original post about the show, and which I think needs to be said, is that I do not blame Lena Dunham, the show’s creator, head writer, and star, for the way HBO advertised her show or the way television critics made her show, before a single episode ever aired, into a text that “speaks” for all of today’s young women. Dunham did not, for example, ever claim that her show was “FUBU” (for us, by us). That unfortunate statement came from a glowing preview written by television critic Emily Nussbaum. I enjoy Nussbaum’s work, particularly the way she writes about female characters on TV, but this was an absurd thing to write (well, to be fair, she was quoting her colleague). In addition to the problem of appropriating the phrase “for us, by us,” which was first used by Daymond John for his 1992 clothing line, FUBU (made by and for African American clientele), the claim that Girls was written for “us” by “us” implies that the white, heterosexual, upper class experience is generalizable to all women.

I suppose I understand why Nussbaum would include this statement in her review of Girls. Sometimes when I watch a film or television show, a moment rings so true that I wonder, briefly, if the creator has somehow read my diary. Knowing that this is impossible — I burned all of my diaries! — I then wonder if perhaps this truthful moment is something “universal.” That is an exhilarating feeling — that a private, personal experience is actually an experience linking me to a larger group of individuals. Indeed, you can feel Nussbaum’s excitement and her joy as she writes about Girls — the show clearly tapped into something personal and true for her. I too had moments like that when I watched Girls this season. But, I am also aware that I will have many more moments of personal recognition than, say, a white woman who had to pay her own way through college, or an African American woman who is looking at the screen and seeing no black faces, or a lesbian who is thinking “Seriously ladies, this is one of the reasons why I don’t date men.” To call Girls a show “for us, by us” implies that all of those other “us-es” don’t count.

My reactions to the Girls pilot probably seems nitpicky. “Okay fine,” you might be thinking,”so you’re mad about the way the show was promoted. But what about the show itself? Isn’t it important to judge it on its own merits?” Yes, hypothetical, puzzled reader, you are right. Let’s talk about the show itself: in my original post about the pilot, I was critical of the show’s tone. I felt that Girls was playing coy with its politics. It felt like Dunham was adding a “first world problems” hashtag (complete with air quotes) to the pilot, rather than actually grappling with these issues head on. I wrote:

…the show is awash in its own privilege. It winks and nods, but then dismisses it as if to say “I acknowledged this okay? Can we move on to what I want to talk about now?” If you have the critical fortitude to acknowledge privilege, like when Hannah’s friend scoffs at her for whining about having to pay her own bills (reminding her that he has $50,000 in student loans), then you better well deal with it.

I was honestly confused about what, exactly, Lena Dunham was trying to tell us about her character, Hannah Horvath. Are we supposed to genuinely sympathize with her “plight” or are we supposed to view her existential struggle to become the “voice of her generation” (or “a voice of a generation”) as the whiny complaints of a young woman whose biggest dilemma is that her ex-boyfriend from college has finally come out of the closet? Or that her shirtless, douchebag lover doesn’t text her enough? Or that her best friend is dating a man with, to quote Hannah’s diary, “a vagina”? If, according to Jason Mittell, the goal of a pilot is “to educate viewers on what the show is, and inspire us to keep watching,” then I do think Girls failed in one of its primary jobs — to let us know what the series’ tone will be. Is it a serious drama with sympathetic characters (Parenthood) ? A broad comedy in which characters are built for punchlines (Big Bang Theory)? A world filled with unlikable characters who do awful things and it’s funny (Curb Your Enthusiasm)? A world filled with unlikable characters who do awful things and it FREAKS YOU OUT (Sopranos)?

The Girls pilot did not make its tone clear. If you take that ambiguous tone, couple it with the show’s overblown hype and claims to authenticity, and then look at the blinding whiteness of its cast, then that is the best way to explain why I (and so many others) did not react favorably to the pilot. But I feel differently now, which is why I am writing this follow up post. I think the tone of the series became crystal clear partway through episode 2, “Vagina Panic,” when Hannah decides to get tested for STDs. The scene opens with Hannah wearing one of those flimsy hospital gowns that open in the back, a piece of clothing that is engineered to make patients feel humiliated and therefore, pliant. As Hannah lays back on the examination table, feet in stirrups, she begins to ramble. I want to pause for a moment and point out that generally I hate the way movies and television depict the “foot in the stirrups” scenario because it is usually played for drama — “My God, Mrs. Smith, you’re seven months pregnant!” — or for comedy — “My God, Mrs. Smith, I’ve found your car keys!”

Instead, this scene reveals the pelvic exam, that necessary female rite of passage, for what it is — very, very, very uncomfortable. I don’t care how old I get, I will never be comfortable having a doctor slide her gloved hand into an area which is normally pretty selective about who may enter it, insert a cold metal instrument inside of me so as to make that personal opening wider, and then have a perfectly casual conversation about my summer travel plans as she examines my holy of holies like a miner digging for diamonds. The pelvic exam is one of the few scenarios in which a woman must act like she is totally cool with a stranger rummaging around in her vagina, not for the purposes of generating an orgasm, but to figure out if there is anything “wrong with it.” So I found Hannah’s verbal diarrhea in this scene to be completely appropriate (even if the content of her ramblings was not). This was my “universal moment,” in which I saw a genuinely frustrating experience from my own life recreated accurately on screen.

The tone of the series also became clear to me here because Hannah, in her attempt to fill the air with conversation, launches into a ludicrous monologue about AIDS. I will quote it at length because it must be read to be believed:

The thing is that, these days if you are diagnosed with AIDS, it’s actually not a death sentence. There are so many good drugs and people live a long time. Also, if you have AIDS, there’s a lot of stuff people aren’t going to bother you about. Like, for example, no one is going to call you on the phone and say ‘Did you get a job?’ or ‘Did you paid your rent?,’ or ‘Are you taking an HMTL course yet?’ because all they’re going to say is ‘Congratulations on not being dead.’ You know, it’s also a really good excuse to be mad at a guy. It’s not just something dumb like, ‘You didn’t text me back,’ it’s like ‘You gave me AIDS. So deal with that. Forever.’ Maybe I’m actually not scared of AIDS. Maybe I thought I was scared of AIDS, but really what I am is… wanting AIDS.

What the hell, Hannah?

A nice recap of the episode over at Press Play compares this scene to a scene in the pilot episode of My So Called Life (1994) in which Angela Chase (Claire Danes) tells her English teacher, during a discussion of The Diary of Anne Frank, that Anne Frank was “lucky.” Angela’s teacher is horrified by her response: “Is that suppsosed to be funny? How on earth could you make a statement like that?” she asks. Angela, who has been mooning over her first real crush, Jordan Catalano (Jared Leto), suddenly snaps out of her reverie. After her teacher prods her again, Angela begrudgingly clarifies her response: “I don’t know. Because she was trapped for three years in an attic with this guy she really liked?” If you’d like to watch this scene, start at the 3.30 minute mark on the video below:

This scene is the epitome of that oft-used term “First World Problems.” Only a young woman who is well fed, well loved, and generally provided for would look at the plight of a little Jewish girl forced into hiding during the Holocaust and be jealous of her. Angela is so caught in the throes of her own teenage crush that she is only capable of viewing the world in terms of young women who get to be with their crushes and young women who are kept apart from them. Even something as large as the Holocaust becomes invisible in this world view. If my daughter said something like that I would be forced to give her a lengthy lecture on the nature of “real problems” even as I know that I possibly said something similarly awful at age 15. Indeed, this moment appears in the My So Called Life to tell us almost everything we need to know about the series’ protagonist, Angela: she is privileged; she is uncomfortable in her own skin; she misunderstands and is misunderstood by the adults in her life; and most importantly, she is desperately in love (or what she believes to be love) with Jordan Catalano. This is all that matters to Angela Chase and so her skewed (and horrifying) analysis of The Diary of Anne Frank makes perfect sense in this context. The audience is not expected to identify with Angela here (unless she is also a privileged 15-year-old in love, in which case, she might) but to understand that this scene is telling us what we need to know about Angela as we move forward through this series.

In the same way, Hannah’s infuriating rant about AIDS is a wonderful crystallization of her character. Only a young woman with no “real problems” would fantasize about having a really real problem. Hannah feels that having AIDS would somehow be simpler and more desirable than having to find a job or a boyfriend just as Angela can only see the benefits of being hunted down by blood-thirsty Nazis. As I listened to Hannah blather on I wanted to chastise her for saying such obnoxious things. But then her gynecologist did it for me. She looked at Hannah and said, with the utmost sympathy, “You couldn’t pay me to be 24 again.” This moment acknowledged Hannah’s self centeredness, her privilege and her ignorance about her own privilege, and then, very carefully, cut her some slack. Hannah is, after all, 23. And if I learned anything from Blink-182, it is that “nobody likes you when you’re 23”:

In fact, people in their early twenties are really no better than people in their early teens. In many ways they are worse because they are now equipped with college degrees that lead them to believe that they “understand” things about “the world.” A recent roundtable discussion in Slate, called “Girls on Girls,” offered this perspective on Hannah’s age:

Isn’t that funny arrogance and vulnerability the special purview of the 22, 23, and 24 year old? You are confused, on the low end of the work totem pole or still trying to prove yourself (unless you’re Mark Zuckerberg), and yet you also are young. You’re the next thing. You’ve left your parents’ home and are free to reject all the posters and accoutrements and funny habits and small town-ness of their lives.

A 23-year-old is like a very independent, very entitled toddler who can drive a car and is legally allowed to drink. We say and do very, very dumb things when we are in our early twenties, and that seems to be what Girls is about.

So as this season of Girls draws to a close, I find myself in an uncomfortable situation. On the one hand, I am really enjoying this series. Not every scene or character works (I could completely do without Shoshannah [Zosia Mamet]), but every episode contains at least one scene that I would characterize as “sublime.” And yes, I am using sublime in the Kantian sense of the word, meaning an overwhelming experience that generates awe and respect. I felt this way when Charlie (Christopher Abbott) serenaded his girlfriend, Marnie (Allison Williams), with excerpts from Hannah’s stolen diary that document their relationship from her cynical and judgmental perspective.

When Charlie gets on stage and announces that his next song was wrriten for his girlfriend, Marnie looks pleased (even though we know she does not truly love Charlie). Then, looking Marnie right in the eye, Charlie sings:

What is Marnie thinking

she needs to know what’s out there

how does it feel to date a man with a vagina.

As I watched this slow-moving car crash I was overwhelmed with a confusing mixture of sadness, humiliation, and awkward triumph. To watch Charlie completely abase himself — to throw himself onto his own sensitive-boyfriend-sword — in order to drive home the point that he deserves to be treated with respect, was truly beautiful. Sublime. As Charlie tells Marnie in a follow up episode, he just wants to be treated “like my life is real.” His song did that. This is the kind of scene that makes me happy that I study film and television for a living.

But still, I keep coming back to my original problem with this show — it makes whiteness and it attendant privilege the default setting (and as John Scalzi recently pointed out, “white” is the lowest difficulty setting in the game of life). Why am I picking on Girls for doing what just about every single TV show currently on the air does? Because Girls is written and produced by an extremely smart and talented young woman and if she can’t find a way to make non-white characters, non-straight characters, or non-wealthy characters the default setting, then who is going to do this? Cord Jefferson’s piece in Gawker really nails this issue:

One of the reasons Girls seems to be so adored is that its depiction of upper-middle class, Urban Outfitters ennui reads as more true than most everything before it, as if, at long last, there is finally a team of young people that “gets it.” Many sub-30, post-college men and women look at the show and nod their heads in agreement with every abortion joke, drug reference, and unfortunate sex scene. This stuff is indeed happening in Ivy League pockets throughout the United States, the only difference is it’s happening to black, Latino, and Asian people as well, not just Dunham and her trio of white friends.

There is currently not a single leading character on Girls that couldn’t be played honestly and convincingly by a black actor or a Pakistani actor or a Taiwanese actor. It may come as a surprise to some Americans, but there are women of all races who freeload off their wealthy parents and work in tony art galleries.

Jefferson concludes his piece with this heart-breaking statement:

The guys begging for money look like us. The mad black chicks telling white ladies to stay away from their families look like us. Always a gangster, never a rich kid whose parents are both college professors. After a while, the disparity between our affinity for these shows and their lack of affinity towards us puts reality into stark relief: When we look at Lena Dunham and Jerry Seinfeld, we see people with whom we have a lot in common. When they look at us, they see strangers.

Like the fictional Charlie, the very real Jefferson wants for television to acknowledge that his life is “real.” Like Charlie, he is tired of sleeping over at the white folks’ apartments all the time and hanging out with their friends. He likes them and all, but he wants them to meet some of his other friends. Like Charlie, Jefferson (and every audience member whose world view is routinely hidden from mainstream television) has his own apartment, filled with cleverly constructed shelving units and lofted beds. But like Marnie, white audiences won’t ever know this until we take the time to visit this apartment and look around. So no, Girls is not unique in its erasure of all that is not white, straight and middle to upper-class. But I wish that it were.

For another reconsideration of the series by one of my fellow blogathoners, check out Jennifer Jones’ “GIRLS at the Half.”

Blogging GIRLS: Reactions to the Pilot

Full disclosure: I am an upper-middle class, highly educated (I have a PhD!), white woman. So when the protagonist of Girls, Hannah (played by the show’s writer/producer/director Lena Dunham), admits to her emotionally distant, sometime-lover Adam (Adam Driver), that her parents have cut her off financially at age 24, and then adds, sheepishly, “Do you hate me?” her mixture of white privilege and liberal guilt reverberated with me. It was a moment of resonance, a particular feeling generated by a particular situation, and I experienced it as a “real” moment.

My guess is that Girls will create lots of resonant moments for many viewers for a variety of reasons. I imagine that some will relate to Marnie (Allison Williams) and her mixed feelings about her too-nice boyfriend or Jessa (Jemima Kirk) and her desire to travel in order to avoid impending adulthood. These are interesting characters. They are messy and imperfect, which is almost always preferable to neat and perfect characters. And I like that Hannah is slightly overweight, or as her fuck buddy assures her “You’re not that fat anymore.” I daresay that this is one of the most radical aspects of Girls: the very ordinariness of its protagonist. As I watched Hannah move across the screen, examining her for an inkling of physical charisma, I was both frustrated and elated. I was frustrated because I am so accustomed to looking at perfectly formed women on TV, with tiny waistlines and flat-ironed hair, that looking at a normal one was a little bit of a let down. But I was also elated by Hannah’s ordinariness and the radicalness of placing a slightly frumpy, slightly average-looking female character at the center of a television series about young women. Jenny Jones offers up a lovely analysis of Hannah’s appetites in her own response to the pilot:

The shot opens with Hannah in close-up but off-center, shoved into the bottom right corner of the shot, breathlessly stuffing spaghetti into her mouth. As the scene continues, she and her father voraciously shovel down food while Hannah’s mother encourages them to slow down. From the start this positions Hannah against her mother and toward her father, an issue which springs up later when her mother is also the instigator for stopping Hannah’s money flow. Hannah is portrayed as consuming carelessly–including sex, drugs, and money–and food does seem to be a primary way that’s characterized. Eating a cupcake in the shower seems to be the ultimate example of this.

I, too, loved seeing Hannah shoveling food into her mouth because I also eat this way and I know it is disgusting. It’s also unusual for a not-stick-thin actress to eat heartily on camera and not make it into a schtick (as Bridesmaids did with Melissa McCarthy’s character). As I watched I asked myself: what if every model and every actress was as average-looking as Lena Dunham? Note that I did not say “ugly” or “fat” (she is neither of these things). She’s just…plain. If film and television were populated with ordinary women would I feel less critical of my own aging body? Would my 5-year-old daughter be less likely to tell me, as she examines her perfectly perfect little body in the mirror,”This shirt makes me look fat”? (True story).

Why is it so rare and exceptional to have an ordinary-looking female protagonist? Ordinary male protagonists are ubiquitous, of course, but for some reason a female character can’t just be smart or powerful or deadly with a broadsword. She has to be fuckable. I don’t want to my 5-year-old to think she has to be fuckable. And the media are working against me and my attempts to bolster her self esteem. And that sucks.

But even as I praise Girls for these praiseworthy elements, it must be acknowledged that there is a wide swath of audience who will have difficulty finding an entryway into this show. As Francie Latour wrote in a recent editorial for the Boston Globe:

It’s a zeitgeist so glaring and grounded in statistical reality that Hollywood has to will itself not to see it: America is transforming into a majority-minority nation faster than experts could have predicted, yet the most racially and ethnically diverse metropolis in America is delivered to us again and again on the small screen as a virtual sea of white. The census may tell us that blacks, Latinos and Asians together make up 64.4 percent of New York City’s population.

Latour’s observations are not in any way surprising. Films and television series are usually not made with a non-white, non-middle class viewer in mind. And when television shows do feature, for example, an all African American cast, it is rare that these shows are allowed to explore the subtle realities of their character’s lives. These shows tend instead to be broad comedies or exploitative reality shows. So no, I’m not surprised that there were no brown faces (no poor faces, no queer faces) in the pilot episode of Girls. But I am disappointed.

No show can (or should) offer to represent all possible identities since this is both impossible and by nature unsatisfactory. But Girls is a specific kind of show. It is a show that aims for verisimilitude — with its focus on the plastic retainer Marnie sleeps in, the scene in which Jessa talks to Marnie while taking a dump and wiping herself (gross, but okay, there was some realism there) and the spartan decor in struggling actor Adam’s apartment. If this show takes the time and care to present the realities of life in New York City for this group of young women in their early twenties, then I do expect to see some homosexuals and some African Americans and definitely some Spanish-speaking characters. It’s New York City for crying out loud! It’s telling that the only person of color to speak a line of dialogue in the entire pilot is a crazy, homeless, African American man who makes a pass at Hannah as she leaves her parent’s hotel room. I mean, seriously, HBO? That’s the role you decided to give to the black guy? [note: I forgot about Hannah’s Asian coworker who asked for the Luna bar and the Smart Water and the Vitamin water. So that’s two POC]. They found a way to bring a British woman onto the show (she’s that Mamet girl’s “British cousin” of course!) so couldn’t an Indian girl be Hannah’s old friend from the weight loss camp her parents made her go to as a tween (I just made up that backstory, by the way)? Couldn’t an African American guy be an actor friend of Hannah’s fuck buddy? There are ways to do this that do not stretch the credibility of this program. And that would make the show more real because I just don’t buy that a girl like Hannah would only interact with straight white people when living in Brooklyn. I do not buy it. And by the way, saying that you wish you could have done this doesn’t count. Consider the following exchange from an interview with Dunham in The Huffington Post:

Are you concerned that people might just think “Girls” is another example of white people problems?

Definitely. We really tried to be aware and bring in characters whose job it was to go “Hashtag white people problems, guys.” I think that’s really important to be aware of. Because it can seem really rarified. When I get a tweet from a girl who’s like, “I’d love to watch the show, but I wish there were more women of color.” You know what? I do, too, and if we have the opportunity to do a second season, I’ll address that.

What? Why could you not do that this season? As the show’s closing credits inform us, you run this show, Ms. Dunham. If your hands are tied, you’re the one who’s tied them.

So is identification necessary to the pleasures offered by Girls? I would argue yes. It is a program that aims to create “real” moments, such as Hannah awkwardly trying to maintain a sexy bondage position while her doltish lover looks for lube and condoms. We are meant to watch this scene and think “Ah yes, I remember having an awkward sexual encounter like that!” And this is not to say that a gay man or a black woman cannot identify with a straight white woman and her awkward, somewhat humiliating sexual experiences. Of course they can. But I don’t think the show is cultivating that identification. I believe this show is zeroed in on a particular kind of viewer, a viewer who is like Dunham: white, middle- to upper-middle class, educated, and liberal. A viewer like me.

Why do I think this? Because the show is awash in its own privilege. It winks and nods, but then dismisses it as if to say “I acknowledged this okay? Can we move on to what I want to talk about now?” If you have the critical fortitude to acknowledge privilege, like when Hannah’s friend scoffs at her for whining about having to pay her own bills (reminding her that he has $50,000 in student loans), then you better well deal with it. Kristen Warner addresses this nicely in her post on the pilot:

White womanhood holds in its grasp innocence. They are the only ones who can truly be innocent. The only ones who can truly and sincerely have a conversation about why working at McDonalds is not an option while waiting on a cup of opium with Jay-Z playing in the background without remotely considering the juxtaposition of all these um…ideas. And the way that the main character, Hannah, and her girlfriends deploy that innocence (in sometimes successful but mostly unsuccessful ways) reveals the invisibility and instability of whiteness.

To offer up a counterexample, the current season of Mad Men is finally starting to do a respectable job of acknowledging its insulated whiteness. In the past Roger Sterling (John Slattery) has been a likable cad, making skirt-chasing, cheating on your wife, and getting drunk at lunch almost (almost) seem charming. But this season Roger has become a dinosaur, an artifact of the white male patriarchy. He is no longer charming. He can’t bring in new clients because he can’t understand that the world is changing. Instead he sits in his office and stews, getting drunker and hazier as the days goes by. In the meantime, Peggy (Elisabeth Moss) puts her feet up on her desk, wears ties, and extorts money from her desperate boss. She is going to replace Roger because she at least understands, in a limited way, that the culture around her is changing. Roger just puts his head in the sand and this will be his downfall.

But Girls does not really address its privilege in a satisfactory way (meaning, I was not satisfied). When Hannah steals the housekeeper’s money we cut to her walking on the street (being harassed by the craaaazy black man) and smirking a small smirk of triumph. What did I need after that scene? I needed a 30 second scene depicting the housekeeper walking into the hotel room, instinctively looking around for her tip, and then muttering something about “cheap motherfuckers” before stripping the bed. That’s all I needed. Just a moment of consequence. Instead, Hannah gets to commit her selfish act in a vacuum and whoosh, it’s gone. Invisible. Quirky.

Am I being picky? A little. Can you judge an entire series based on its pilot? No. But let me explain myself through a teaching analogy: when I am grading essays I tend to be harder on my best writers. I challenge them more on their ideas, get more annoyed at their grammatical errors, and more outraged at their lazy arguments. “I know you are capable of better work than this” I might write at the end of a perfectly respectable essay. If you have the ability and the intelligence, then why create something subpar? I’m taking the same critical eye to my study of Girls. Dunham is a great writer and a pretty good actress with an ear for smart dialogue, and I know she can do better. Do better, Dunham, you are capable of better work than this. I give you a B. I know you can get an A.

For more reactions to Girls, I encourage you to check out our Facebook group, which is the hub of our Girls blogathon.

THE WONDER YEARS, Involuntary Memory, and Mourning

In 1988 I was 12 years old. I was a 6th grader at the Susquehanna Township Middle School. I lived in the suburbs. I had never kissed a boy. I wore giant Sally Jesse Raphael-style glasses and every day was a bad hair day. In other words, I was a pretty typical 12-year-old kid.

Therefore, despite our gender differences, I felt a strong kinship with Kevin Arnold (Fred Savage), the protagonist of The Wonder Years. Kevin was also a typical 12-year-old kid: he was alternately moral and selfish, brave and cowardly, kind and cruel. He knew better than to question his parents and teachers, but he did it anyway, and suffered the consequences. He had an older brother who tortured him and a father who worked a lot and said very little. He was grappling with an adult world he only partially understood, but felt its ramifications as strongly as any adult. Kevin was me, only in a boy’s body.

If you are unfamiliar with this program for some reason, The Wonder Years was a 30 minute comedy/drama that ran on ABC from 1988-1993. The series opens in 1968, when protagonist Kevin Arnold (Fred Savage) is starting junior high. Throughout the series Kevin’s personal coming-of-age story runs parallel with America’s very different, public coming-of-age story. As Kevin becomes more of an adult, America is also coming to terms with a new kind of adulthood: Vietnam, 2nd wave feminism, the Black Power movement, hippies, free love, a man on the moon, you get the picture. In episode 4, “Angel,” Kevin’s older sister, Karen (Olivia D’Abo), introduces the family to her radical boyfriend, Louis (played by a very young, very handsome John Corbett). Kevin takes an instant dislike to Louis because he makes out with his sister on his parents’ lawn (gross!) and because, as Kevin’s voice over explains: “I don’t know what it was about Louis that I didn’t like. Guess there was something about him I didn’t understand.” Here we catch a glimpse of Louis’ spray-painted VW van, with the words “Somethings Happening” scrawled on the door. To Kevin, those words were ciphers, shorthand for a movement that he was too young to comprehend. Louis and his leather vest and VW van were something, to use Kevin’s words “that [were]…taking my sister away from us.”

When I watched this episode at age 12, those words were also meaningless to me. A spray-painted van and long hair signified “hippie,” but I didn’t actually know what a hippie was. To me, “hippie” was a costume worn at Halloween rather than a representative of a political movement. What I didn’t know then is that in 1968, a younger generation was beginning to question the way the world worked. They saw their parents as sleep walkers, as drones who had yet to be enlightened about “what’s going on.” For example, in the same episode Louis has dinner with Kevin and the rest of the Arnold family. When Norma (Alley Mills), Kevin’s mother, mentions that the son of a family friend was recently killed in Vietnam, a heated conversation ensues. I am quoting this scene at length because it is a testament to both the pitch-perfect writing of this series and the respect it has for its characters. No one is a caricature and no one is a “symbol” of his or her generation:

NORMA: One of the boys on our block was killed in Vietnam several weeks ago.

LOUIS: Oh, I know. I mean, uh, Karen told me. Another meaningless death.

JACK: I beg you pardon?

LOUIS: I just meant that…it’s just a shame, uh…a kid has to die for basically no reason.

NORMA: More broccoli, anyone?

JACK: I don’t think it’s meaningless when a young man dies for freedom and for his country.

LOUIS: I just have a little trouble…justifying dying for a government that systematically represses its citizens.

NORMA: Oh, honey. Try the potatoes – I put grated cheese on them.

JACK: What the hell is that supposed to mean?

KAREN: It means the United States government is responsible…For the oppression of blacks, women, free speech…

JACK: Well perhaps, little lady, you’d like to go live in Russia for a little while…

LOUIS: Oh, uh…I think what Karen is saying is that –

JACK : Look, buster! I happen to believe that freedom and democracy have certain advantages that Communist dictatorships don’t, and that is what Vietnam is all about!

LOUIS : No, man, that’s what they brainwash you to believe it’s all about.

JACK: So…you think I’ve been brainwashed, do you, Louis?

LOUIS: No. No. Look… I think anyone…who supports the American war effort in Vietnam…[shrugs]…is having the wool pulled over his eyes.

JACK: I see…

LOUIS : Just like they did with Korea.

JACK: [getting angry] What the hell do you know about Korea? I was in Korea. I lost a lot of good friends there.

KAREN: Daddy, that doesn’t have anything to do with what we’re saying.

JACK : And they weren’t brainwashed! They were brave men who weren’t afraid to fight for what they believed in. Now if you’re afraid to fight – why don’t you just say so?! Why don’t you just admit you’re chicken?

LOUIS: You’re damned right! I am chicken. I don’t want to die like your friends! What do you think that you achieved over there? Hmm? Do you think that those people are free? They’re not free, man.

JACK: That’s crap!

LOUIS : You were used, man, and your friends were used.

JACK : That’s crap!

KAREN : Daddy, you never listen to what we say! Some of what we say is true!

LOUIS: Don’t accept all this death and then justify it. It is wrong! Your friends should be alive – they should be…[gestures]…enjoying dinner, and arguing with their kids, just like you are.

JACK: What do you know about it?! Who the hell are you to say that?!

When I watched this scene in 1988, I don’t think I understood the nuances of the argument. I saw it much the same way that Kevin sees it: one more fight in a long string of fights that he has witnessed between his sister and his parents.

But recently my husband and I began rewatching this series (it’s streaming on Netflix RIGHT NOW) and I was struck by the honesty of this scene. It would have been easy to make Jack an out-of-touch defender of the old guard holding on to his ideals, even as he sees them crumbling around him. Yet, Jack is sympathetic here and so is his point of view: He fought in Korea. He served his country. Now he is enjoying his reward (or trying to): a comfortable home in the suburbs with his wife and children. When Louis, who could also come off as a radical caricature but doesn’t, begins to poke holes in Jack’s worldview, there is a sadness there. Louis is not enjoying this argument. You can feel that Louis is angry, which we expect, but what I love about this scene is that it also legitimizes Jack’s anger. When he snaps, “What do you know about it?! Who the hell are you to say that?!” you can feel the rage and betrayal of Jack’s generation. How does this hippie know anything about the way the world works? Where is his authority to speak? And why is his hair so damn long?

This scene was just one of many that has resonated with me in new ways since I began rewatching The Wonder Years, some 24 years after it first aired. This experience has resulted in a doubled viewing position. On the one hand, I am watching as a 35-year-old and so the historical and cultural touchstones that I missed when I was 12 (the changing meaning of the suburbs in America in the 1960s; the anti-war movement; the students protests of 1968; The Feminine Mystique) are suddenly visible and significant. But at the same time, as I watch, I am still watching as a 12 year old.

When I sat down to watch the pilot episode a few days ago, and the opening credits began to play, I felt crushed, not by nostalgia, but by the weight of being 12. Those credits, a faux-scratchy home movie of Kevin Arnold and his family enjoying their last days of innocence, were etched onto my brain so that each frame was a surprise and a memory.

This experience was like reliving entire pieces of my adolescence (complete with the attendant emotions) while simultaneously having the ability to contemplate these pieces of my youth from the detached perspective of an adult. When I was 12 I so strongly identified with Kevin Arnold that when Winnie Cooper walks up to the bus stop in the pilot episode, having shed her pigtails and glasses for pink fishnet stockings and white go-go boots, I too, fell madly in love with her. Even at 35 I was hit by that excruciating longing and terror so characteristic of 12-year-old desire. I was in the past and the present at the same time. Here is the scene below (start watching at the 1.30 mark):

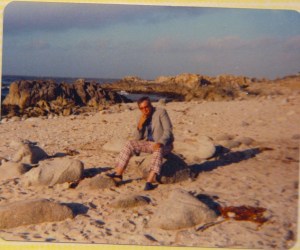

Because of this doubled viewing position, revisiting The Wonder Years has been therapeutic for me. You see, almost three months ago, my father died. I will not say that he “passed away” since this term implies a softness, like falling asleep or slowly vanishing. Death can be like this, but this was not my experience of it. And when I returned to my regular life, after the funeral and the sad faces and the conversations I didn’t want to be having, I encountered a steady stream of condolence notes, tentative e-mails, and awkward conversations with well-meaning colleagues about my winter break. One condolence note in particular stood out to me. Here is what it said:

“My Dad died when I was 30. I remember being surprised at how his death could make me feel like a child again.”

This note made me think about my experiences sitting in my father’s beige hospital room with my mother and brother. As we sat there together I realized that it had been almost a decade since the four of us had been alone together; no spouses, no children, no reminders of the lives that we had built apart from the original family unit. Whether we liked it or not, the three of us were transported back to an earlier time in our lives and into roles we had long since abandoned. I was once again a daughter and a sister rather than a wife and mother. I suddenly felt like a child again.

Perhaps this is why, some three months later, I have been finding so much comfort in the past: looking through old photo albums, creating Pinterest boards chronicling my youth, and yes, rewatching shows from my childhood, like The Wonder Years. This choice is fitting, in a lot of ways, since almost every episode of The Wonder Years contains a shot, or an entire scene, that focuses on the Arnold family watching television. These scenes focus on iconic TV moments, of course, such as when Kevin and his family watch the crew of the Apollo 8 orbit the moon:

But we also see the family in more mundane television-viewing scenarios. The TV is a way for the family to bond and a way for them to escape from each other. In the pilot Kevin even addresses the primacy of television after experiencing one of the most important landmarks of his adolescence: his first kiss:

“It was the first kiss for both of us. We never really talked about it afterward. But I think about the events of that day again and again. And somehow I know that Winnie does too, whenever some blowhard starts talking about the anonymity of the suburbs or the mindlessness of the TV generation. Because we know that inside each one of those identical boxes, with its Dodge parked out front and its white bread on the table and its TV set glowing blue in the falling dusk, there were people with stories, there were families bound together in the pain and the struggle of love. There were moments that made us cry with laughter, and there were moments, like that one, of sorrow and wonder.”

These words are a defense of suburban life with its “little boxes made of ticky tacky,” but they are also a defense of television watching itself. Kevin argues that although his generation seems to be living in identical houses and watching indentical shows on their indentical TV sets, that doesn’t mean that their experiences of the world aren’t unique, meaningful, and real. For Kevin, TV doesn’t detract from his reality. It is a meaningful part of his reality. Mine too.

***

When people write about a moment in the present sending them back in time, they almost always cite Marcel Prousts’ seven volume novel, Remembrance of Things Past (1913-1927). There’s a reason for the ubiquity of Proust quotes in writings about memory: the dude nails it. So here’s Proust talking about how eating a madeleine cookie and a hot cup of tea generated an “involuntary memory”:

“No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory – this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. I had ceased now to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I sensed that it was connected with the taste of the tea and the cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savours, could, no, indeed, be of the same nature. Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it?…”

Rewatching The Wonder Years is performing the same spell on me as Proust’s madeleine did on him. Take for an example, the episode, “My Father’s Office,” in which Kevin attempts to understand why his father is so tired and grumpy when he comes from working his job as a middle-management drone in an ominous sounding place called NORCOM. After asking his father a few questions and receiving only unsatisfactory answers, Kevin agrees to go to work with him for the day. He sees that his dad has a lot of power, which makes him proud, but that he must also answer to a needling boss, which embarrasses him slightly. Over the course of the day, Kevin comes to understand that the trials his father endures everyday have nothing to do with being his father. He also learns that his father once wished to be a ship’s captain, navigating his vessel by watching the stars. This blows Kevin’s mind.

The episode concludes with Kevin joining his father in their yard to look at the stars. Up until this point, star-gazing had been something Kevin’s father did alone, when he was angry or frustrated. Kevin often watched him do this through the window with a mixture of curiosity and fear. But at the end of this episode, Kevin joins his father and they share this experience while strains of “Blackbird” play on the soundtrack.

Of course, as Kevin points out, understanding comes with a price: “That night my father stood there, looking up at the sky the way he always did. But suddenly I realized I wasn’t afraid of him in quite the same way anymore. The funny thing is, I felt like I lost something.” I’ll admit that at age 12 I did not quite understand the meaning of Kevin’s epiphany (he always concluded the episode with an epiphany well beyond his young age). I, too, had a hard time seeing my father as a “real person” but I didn’t see why such an understanding would also be a loss. In fact, it has only been in the last few years, as I’ve watched my father’s body deteriorate and his attendant anger and humiliation, that I understood what Kevin Arnold meant. He meant that when we are able to see our parents as something other than a servant of our needs, our relationship with them changes. Once we realize that our parents have feelings and desires that have nothing to do with us, we understand them better. They become people, rather than parents. But we also lose a piece of our childhood once we gain that understanding. This is a loss that needs to be mourned. And sure enough, as the credits rolled on “My Father’s Office,” I cried.

Over the last few months, I have been stumbling through my own grief. I thought it would move in a straight line, but it moves in circles, disappearing and returning. When the grief moves away, I enjoy the freedom and respite. But when it circles close I try to grab it and confront it. It may sound strange, but the involuntary memories evoked by The Wonder Years are helping me to work through my grief and bring it close. Proust writes:

“But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.”

The Wonder Years is filled with such remembrances, structures of feelings I have long forgotten and which I doubt I could access in any other way. We all mourn in our own ways and in our own time. For now, I think, I’ll take my mourning in 30 minute journeys to my past, when my parents were both still my “parents” and when I had not yet become a parent myself. For some, nostalgia can be toxic and overwhelming but for me, right now, it is as comforting as a plate of madeleines, a cup of hot tea, and a seat on the couch in front of the glowing box.

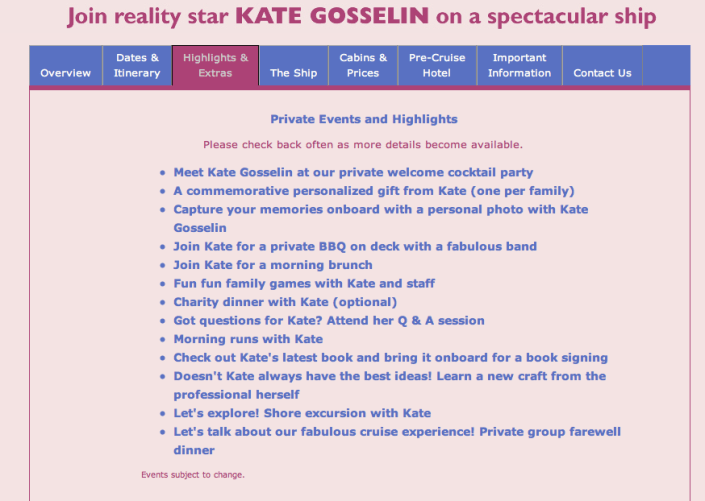

Nota Bene #3: Cruising with Kate Gosselin

This is real, dear readers. Kate Gosselin, former star of Jon & Kate Plus 8, and more recent star of the “Celebrity Plastic Surgery Gone Wrong” section of your favorite tabloid, is partnering with Royal Caribbean to give vacationers the cruise experience of a lifetime! The cheapest cabin on this cruise is $3,000 and the priciest is $5,500. That doesn’t include the roundtrip airfare to the port of embarkation, 7 days worth of booze, and mandatory tips for the various staff who will be shoving complimentary ice cream sundaes in your face 24-hours a day. And you’ll need someone to watch your cat while you’re gone. That’s gonna cost you too. Especially when your cat finds out why you’ve abandoned her for 7 days and 7 nights (hint: pee in shoes).

It’s not that I doubt that there are people out there who would like to meet Kate Gosselin, or at least see her in person. If Kate Gosselin was coming to the Greenville Olive Garden, I would most definitely drive across town to see her. I’m a gawker by nature. I might even wait in a line to see her. Especially if there was the promise of endless breadsticks and salad afterwards.

What I doubt is that there are enough people to fill a cruise ship who have 1. the desire to meet Kate Gosselin and 2. several thousand dollars of disposable income. But clearly some vacant-eyed minion in Kate Gosselin’s employ must have gotten on the blower, done some canvassing, and found out that YES! there are in fact at least 3,000 people willing spend a lot of money to “learn a new craft” with Kate Gosselin somewhere in the Caribbean. Kate makes amazing crafts.

Who might these people be? I imagine these are people who have worked very hard to create a nice nest egg for themselves, one that they’ve been squirreling away for a big splurge. They are willing to spend this money on a worthwhile venture — something the whole family can enjoy. I imagine a mother of three young children, a woman who still believes that Kate Gosselin is her former self, a domestic super hero who manages to “do it all.” She does not see Kate Gosselin’s current self: a strung out fame addict making due with celebrity cruise ship gigs (which, if you didn’t already know, are the methadone of fame fixes, followed only by state fair appearances). I believe this target consumer is a generous, good-hearted woman. She thinks that Kate Gosselin got an unfair shake when her marriage to fell apart in front of the reality TV cameras and what was poor Kate to do but scramble for more TV gigs in order to make ends meet while her lazy, good-for-nothing ex-husband shopped for Ed Hardy T-shirts and had sex with young women who should know better? Lancaster county private schools don’t pay for themselves. And neither do unlimited sessions at The Sunshine Factory.

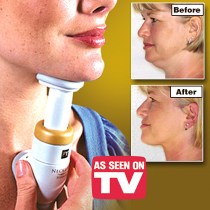

Yes, the ideal passenger on the Kate Gosselin cruise is a woman who doesn’t like to gossip, but enjoys reading gossip rags. When the cover of US Weekly proclaims “Angie is Pregnant!” she believes them and wishes the best for Angie. She owns several products featuring the “As Seen on TV” sticker. They have to work. Why would Ron Popeil lie?

This woman sees the Kate Gosselin cruise as a chance to play “fun family games with Kate and staff,” no doubt envisioning being tethered to Kate in the 3-legged race or possibly depositing an egg, ever-so-gingerly, onto Kate’s awaiting spoon. I imagine this mother has twins, just like Kate, or possibly triplets or quadruplets (but definitely not sextuplets because then this woman would also have her own show), and that’s why she identifies with Kate in the first place. She understands why Kate was so frazzled — why she barked at her children and needled her husband. She’s done that too. Having multiples is tough.

This woman might be a stay at home mom (but only temporarily, just until the twins are old enough for school) and the days are long. Some days she wonders why she keeps wiping crumbs off of the counter top after breakfast, knowing that they’ll reappear again, like magic, after lunch. She wonders why she bothers changing her clothes before loading the triplets into the minivan and heading to the grocery store. After all, she’ll be wearing her winter coat — no one will see the dribbles of coffee on her chest or the dried rice cereal clinging to the cuffs of her sleeves. But there’s always the chance. She brushes her hair, too, and puts on a little lipstick even when she knows she’ll be at home all day, just her and the quadruplets. Grooming’s important. Because you just never know who might show up at the door while you’re sitting there, not wearing any lipstick. She and Kate understand this.

She’s sympathetic to Kate and her Botox and her hair extensions and her tummy tucks. She wouldn’t mind getting a tummy tuck herself. Who wouldn’t? She plans to tell Kate all of this at that “private BBQ on deck with Kate and a fabulous band.” She’s thinking that “private” sounds nice. Maybe she and Kate will share their birth stories. Hers is a real doozy — 40 hours, no epidural. Not even a valium. She practiced her visualization and guided imagery ahead of time, thinking of her uterus as a flower slowly opening, just as her Bradley method teacher instructed. Not many women can do that. Maybe they’ll stand together at the railing, this target consumer and Kate, looking out at the ocean, quoting Titanic (“I’m king of the world!”). “Yes,” she thinks, “this could be the family’s summer vacation. Pricey, yes. But we can swing it.” And won’t it be nice to get a “A commemorative personalized gift from Kate” (one per family)? The gift will be personal because Kate understands her, just as she understands Kate.

I understand this woman, too, because part of her is me. And I think this woman deserves better. She deserves to use that $5,000 nest egg on something real and tangible — not a staged photograph with a curt former reality TV star. But she enters her credit card information. She understands the ticket is non-refundable. She’s going to meet Kate Gosselin. It’s worth it.

The Myth of the Ugly Duckling

Last year I wrote a blog post detailing my biggest television pet peeves because TV shows are filled with conventions that are used and reused until they drive their audiences nuts. Repetition is part of popular culture. There’s even an entire website devoted to annoying, overused TV tropes. Sure, we must accept the easy shorthand of the TV trope if we are going to watch TV, but ever since I started seeing ads for Zooey Deschanel’s new comedy, New Girl , I’ve been thinking a lot about one particular trope that I’ve always hated. It goes by many names, but for the purposes of this post, let’s call it “the myth of the ugly duckling.” You all read “The Ugly Duckling” when you were a kid, right? First published in 1843 (thanks Wikipedia!), Hans Christian Andersen’s famous story is about an unattractive baby duck who is abused by all who meet him until finally, one glorious day, he realizes that he is actually a beautiful swan! Here’s how Andersen’s story concludes:

He had been persecuted and despised for his ugliness, and now he heard them say he was the most beautiful of all the birds. Even the elder-tree bent down its bows into the water before him, and the sun shone warm and bright. Then he rustled his feathers, curved his slender neck, and cried joyfully, from the depths of his heart, “I never dreamed of such happiness as this, while I was an ugly duckling.”

The lessons in this classic tale are clear: If people bully you based on something you cannot control, such as the fact that you are “ugly,” don’t worry. Eventually, you will be accepted by a group of much better looking people. These people will embrace you and love you based on something else you cannot control, the fact that you are now “beautiful” and look just like them. Good for you, little duck!

Obviously, this message of “beauty as transcendence” is problematic and highly damaging to the psyches of young children and insecure adults alike. But that’s not why I dislike the myth of the ugly duckling. I dislike it, and its many iterations in popular culture, because the ugly duckling is not “ugly.” I mean, have you seen a baby duck (or a baby swan) before? Let me refresh your memory:

Obviously, this message of “beauty as transcendence” is problematic and highly damaging to the psyches of young children and insecure adults alike. But that’s not why I dislike the myth of the ugly duckling. I dislike it, and its many iterations in popular culture, because the ugly duckling is not “ugly.” I mean, have you seen a baby duck (or a baby swan) before? Let me refresh your memory:

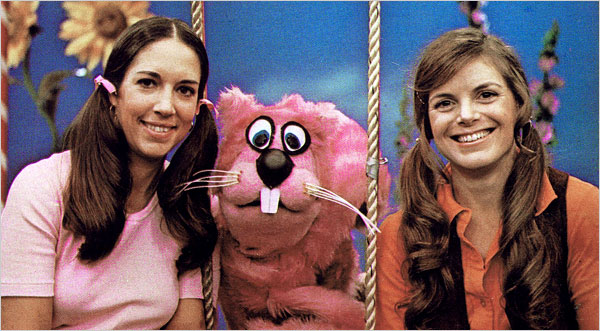

And that’s pretty much the problem I have with the myth of the ugly duckling when it is translated into a film or TV show. It’s simply untrue. Don’t tell me someone is ugly when they are so clearly NOT ugly. My first exposure to this myth, as applied to women, occurred when I was about 6-years-old and watching my favorite channel, MTV:

Thank goodness “Goody Two Shoes” was in heavy rotation in 1982; it communicates so many important lessons about beauty, sexuality, and male-female relationships. The most important lesson Mr. Ant taught me is that women who wear suits, buns, and glasses are highly unattractive. Even when they are so clearly hot. This was upsetting to me because at the time I wore a large pair of glasses, quite similar to the pair worn by the woman featured in the video, and I often wore my hair pulled back. Also, I did not drink or smoke. “Shit,” my 6-year-old self noted, “I’m ugly!”

But not to worry. According to this video, it is easy to capture the attention of the wily Adam Ant. All you need to do is shake your bun out and remove those giant glases. Viola! Ant Ant is totally going to screw your brains out in that hotel room while his horny butler watches through the keyhole. I should also note this video’s plot, about an uptight looking woman who appears to be interviewing Adam Ant, and then decides to let her hair down (literally) and make sweet love to the rockstar, has very little to do with the song’s lyrics. The lyrics themselves (you can read them here), seem to be a critique of image and stardom and of the very transformation the woman makes. But my 6-year-old self was not listening to the lyrics. I was watching the video. And taking copious mental notes.

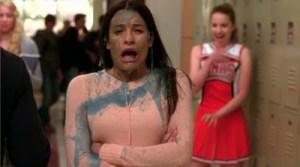

Fast forward a few years to one of my all-time favorite films, The Breakfast Club (1985, John Hughes). I did not see this film in the theater, but by the time I was in junior high it seemed to be playing on TBS every single Saturday afternoon. Like most kids of my generation, everything I thought I knew about being a teenager came from this film (or some other John Hughes film). Some of the film’s many lessons include: bad boys are sexy, girls who don’t like to make out are prudes, Claire is a “fat girl’s name,” detention is wicked awesome, and, most importantly, if you want cute boys like Emilio Estevez to think you are pretty, stop being so weird and interesting and let the popular girl give you a make over. Ally Sheedy, I am talking to you.

Even as an insecure preteen I noted with dismay that the pre-makeover Allison was actually very, very pretty. After all, she’s played by Ally Sheedy! Ally Sheedy is a fox! Her “make over” doesn’t alter her appearance in any kind of radical way, much as the removal of a bun and glasses doesn’t change much about the goody two shoes in the Adam Ant video. Both of these women were beautiful from the start and the only people who insisted on their physical unattractiveness were the creators of these texts. In other words, almost every ugly duckling I have encountered, dating all the way back to Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, have never truly been “ugly.” Their ugliness is an artifice I have been asked to believe so that the beautiful, swanlike transformation that inevitably follows can happen. Time and again, beautiful women are cast in the role of the “awkward,” “drab,” “dorky,” or “ugly” girl. And all it takes to make them “ugly” is a pair of glasses, a disinterest in fashion, or a quirky hobby.

At this point you might be thinking: so what? Who cares if film and TV audiences are repeatedly asked to view highly attractive women as “ugly”? I guess my problem with all of this is that in these films and television shows I am told, over and over, that certain key signifiers make attractive women into unattractive or undesirable women. These signifiers include but are not limited to:

Being a tomboy and an awesome drummer:

Being poor:

Being Aaron Spelling’s daughter:

Wanting to be an artist:

Having musical talent that far outstrips that of your peers:

Being smart and wearing glasses:

In every case, the decision to be studious or artistic or slightly different from everyone else transforms a woman who would normally have more suitors than an alley cat in heat into a lonely spinster. So the message is: ugly women are screwed. And pretty women who value something other than being pretty are screwed. And if you are ugly and you like to read? Well, start collecting cats and Hummel figurines now because you have a lonely life ahead of you, spinster.

And that is why I could not bring myself to watch the premiere of New Girl. I just could not stand the way that Zooey Deschanel’s character, Jess, was repeatedly described as being “dorky” and “awkward” in press releases and in early reviews. I don’t care how big her glasses are or how often she bursts into song at inopportune times. Zooey Deschanel is not a “dork.” She’s hot. Can a woman who is that beautiful really and truly be a “dork”?Now I’m not saying that hot chicks don’t get dumped, as Deschanel’s character does in the show’s premiere. And I’m not saying that hot chicks don’t find themselves feeling awkward or acting the fool. I am sure they do. But it’s hard to buy a woman like Zooey Deschanel as a true awkward dork. You know who plays good dorks? Kristen Wiig. Someone else? Charlyne Yi. I believe her.

Just not another hot chick in glasses.

It’s time for film and TV to get a new trope. Make a character a social outcast because she’s a bully or because she’s too judgmental. Not because she wears glasses or reads books or carries a big purse. After all, you need a big purse to carry all those books. And you need glasses to read those books. Just sayin.

Premiere Week 2011!

This might come as a shock to those of you who regularly read this blog, but … I love TV. And although the “fall television season” is not what it used to be now that so many television series premiere in the winter and even the summer, there are still plenty of new shows to be excited about. That’s why I volunteered to write some short reviews of two particularly exciting series premieres, The CW’s Ringer and NBC’s Up All Night, over at Antenna.

My short reviews of Ringer (click here) and Up All Night (click here) are live now. If you are simply too lazy to read these 300 word reviews (and I can appreciate that kind of laziness), I will summarize for you: Ringer is a Sarah Michelle Gellar vehicle about twins, mirrors, and identity theft (meh) and Up All Night is a surprising funny comedy about how babies ruin your otherwise super-awesome life (check it out!). There are no vampires in either program. Yep, that bummed me out too.

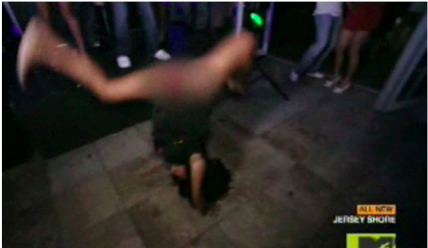

Performing Gender and Ethnicity on the JERSEY SHORE

This summer I had the good fortune of being accepted to the “Gender Politics and Reality TV” conference hosted by University College Dublin. I knew it would be difficult to attend this conference–it coincided with the first week of classes at the university where I work–and I knew it would be expensive. But I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to attend a small conference that was entirely focused on reality television. I am starting a new research project on MTV-produced reality shows and I thought this conference would help to kickstart my writing and research. So I planned well: I applied for and was awarded an international travel grant to help pay for the expensive trip, I enlisted two wonderful colleagues to teach my first week of classes for me, and I finished my paper and visual presentation a full week ahead of schedule. The night before I was set to fly to Dublin, I was finishing up my packing and it was only then that I thought to take a look at my passport. I had not flown out of the country since 2006 and I had no recollection of when the document was set to expire. It expired in 2008. Ooops.

I won’t describe the panic that followed this realization. I will just say that it took me about 2 hours of phone calls and internet research to conclusively determine that there was absolutely no way for me to get an updated passport in 24 hours (surprise!). I was going to have to cancel my trip to Dublin. I would like to offer a good explanation for why I purchased an international power adapter two weeks before my departure but only thought about my passport — the only way to legally leave my country — 24 hours before my departure. But I don’t have one. To a Type A personality like me, such an oversight is unthinkable. Like Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) in Memento (2000, Christopher Nolan), I have constructed a series of elaborate tricks to ensure that I remember to complete the many tasks required of a full-time working mother of two: alerts on my phone, copious notes in my planner, lists, lists and more lists. But this time, my system failed. Where was my Polaroid photograph? Where was the tattoo, written backwards across my chest, reading “GET PASSPORT RENEWED 4-6 WEEKS BEFORE DEPARTURE“?

There are many reasons why missing this trip was devastating to me: the expensive plane ticket, the embarrassment of contacting the conference organizer (a woman I greatly admire) and explaining what had happened, the loss of a much-needed vacation from my children (I love them, but sometimes Mama needs to get away), the chance to meet and talk shop with reality TV scholars in the context of a small, intimate conference, and the lost opportunity to present my work-in-progess to these experts and get their much-needed feedback. I can’t do much about the first four things, but I can, in fact, do something about the fifth. Although a friend attending the conference offered to read my paper for me and thus ensure that my mistake did not derail my panel (Thanks Jon!), I won’t be there for the conversation that follows. So I’ve decided to post my entire paper here on my blog (minus the clips, because I have yet to upgrade my blog so that I can upload my own clips). If you have an interest in subcultures, gender studies, or reality television, please read my paper below and offer me some feedback. While you do this I’ll be drinking a green beer and dreaming of Ireland…

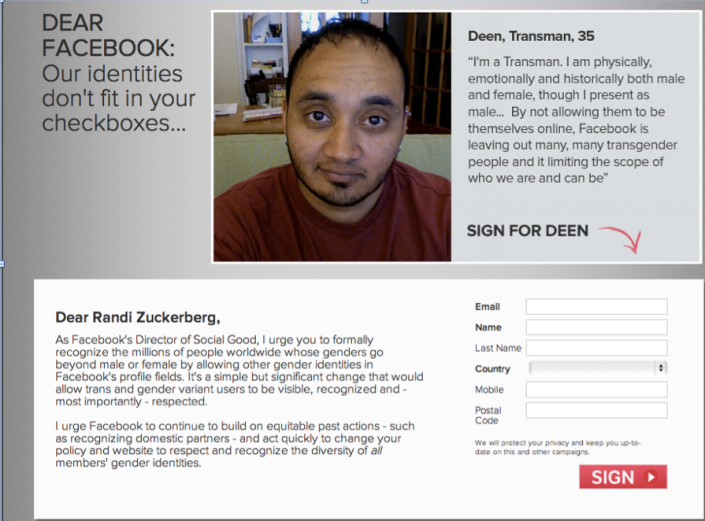

Over the last few weeks an open letter to Randi Zuckerberg, the manager of marketing initiatives at Facebook, was circulated around various social media sites. The letter urges Zuckerbeg to “formally recognize the millions of people worldwide whose genders go beyond male or female by allowing other gender identities in Facebook’s profile fields.” The letter, which also serves as a petition, includes a series of testimonials from Facebook users who believe that the terms “male” and “female” do not accurately reflect their personal experience of gender, where gender is, to quote Robyn R. Warhol, “a process, a performance, an effect of cultural patterning that has always had some relationship to the subject’s ‘sex’ but never a predictable or fixed one” (4).

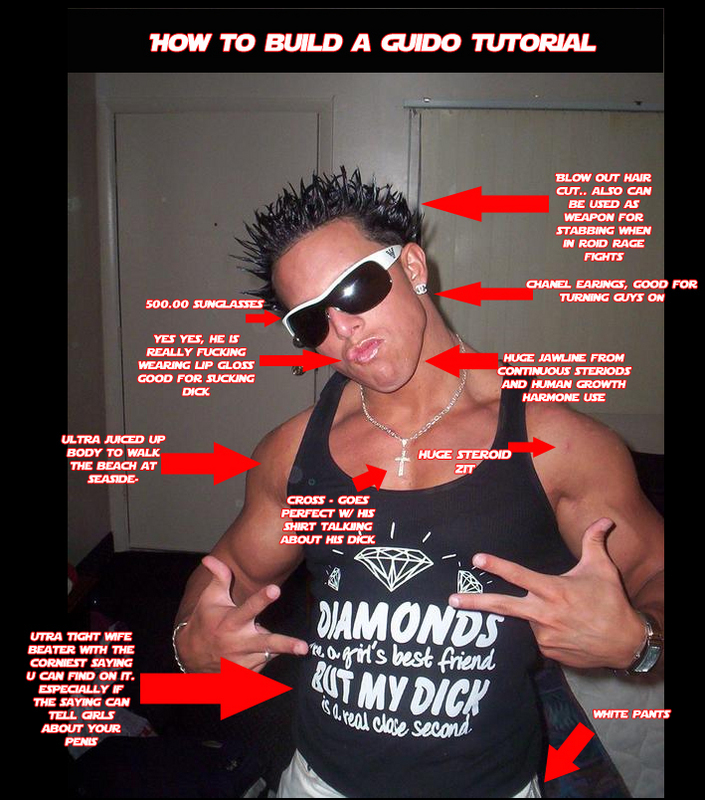

As I read through these testimonials, my mind drifted to MTV’s top-rated reality series, Jersey Shore, as I could imagine one its stars, Pauly D, submitting his own testimonial. If he did, it might go something like this:

“I am a heterosexual man who proudly spends 25 minutes styling my hair. I have earrings in both of my ears and have been known to wear lipgloss. I do not fit into Facebook’s limited gender categories.”

Okay, so Pauly D probably would not write a testimonial about his fluid understanding of gender, but he should. In this paper I argue that the guido identities celebrated in Jersey Shore reconfigure the way gender performs within the context of this Italian American subculture. When men like Pauly D adopt the styles, behaviors, and interests that U.S. culture has enforced as appropriate to women’s bodies, they, paradoxically, feel more like masculine men. In other words, Jersey Shore, for all its misogyny and ethnic stereotyping, actually highlights the performative nature of gender, and how it must be understood as a contingent and multiple process, rather than as a preexisting category (Warhol 5).

Before I go any further, I want to acknowledge that the term “guido” has a troubled history; some factions of the Italian American population see the term as offensive and view Jersey Shore’s cast members as minstrel-show caricatures (Brooks). Other Italian-Americans have reclaimed and reappropriated the moniker as a source of ethnic pride. Still other groups acknowledge that the term exists and therefore seek to understand and unpack its meanings.

My use of the term is neither an endorsement nor a rejection of any of these points-of-view. Instead, I deploy the term “guido” as a way to reference the ethnic subculture that is showcased, celebrated, and derided on Jersey Shore and in the process I hope that I do not cause any offense.

The term guido refers to a specific subcultural identity signified by a series of distinctive clothing styles, music preferences, behavioral patterns, and choices in language and peer groups. This label provides coherence and a solid ethnic character to a set of stylistic choices — including a preference for big muscles, gelled hair and tanned skin — selected by this particular youth subculture. Sociologist Donald Tricarico argues that the term guido denotes a way of being Italian that is linked to an ensemble of youth culture signifiers. He writes: “To this extent, ethnicity also draws boundaries intended to include some and exclude others. It establishes parameters for stylized performances in the competition for scarce youth culture rewards” (“Youth Culture” 38). In addition to the usual rewards of peer acceptance and recognition as a member of the subculture, embracing the signifiers of the guido subculture provides the Jersey Shore’s cast members with fame, money, and lucrative business opportunities. And because MTV provides such powerful incentives for Jersey Shore cast members to perform their ethnicity on national television, MTV’s cameras artificially inflate the signifiers of the subculture. Thus, Jersey Shore becomes a unique opportunity to analyze the performative nature of gender within the framework of an ethnic subculture. In this context “performative” does not just refer to gender as a performance; I am also using the term as a way of understanding, to quote Warhol again, “the body not as the location where gender and affect are expressed, but rather as the medium through which they come into being” (10). In Jersey Shore, gender performs in a unique way in that behaviors typically coded as effeminate actually constitute—rather than negate—masculinity.

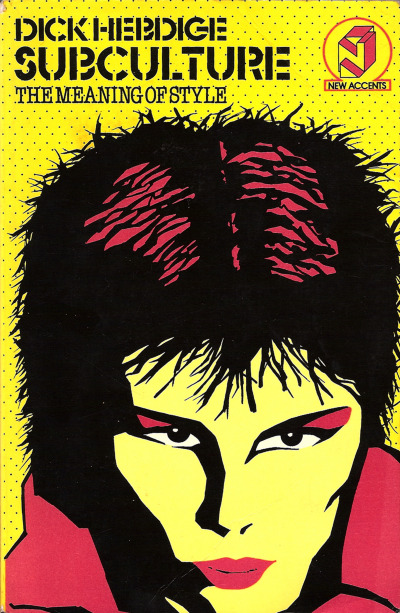

According to Dick Hebdige, every youth subculture represents “a different handling of the ‘raw material of social existence’” (80). While subcultures represent countercurrents within the larger hegemonic structures of society, they are nevertheless “magical solutions” to lived contradictions. In other words, although subcultures initially pose a “symbolic challenge to a symbolic order,” these subcultures are inevitably, almost instantaneously, recuperated into the very system they are supposedly challenging (Grossberg 29). According to Tricarico, the guido “neither embraces traditional Italian culture nor repudiates ethnicity in identifying with American culture. Rather it reconciles ethnic Italian ancestry with popular American culture by elaborating a youth style that is an interplay of ethnicity and youth cultural meanings” (“Guido” 42). Because Italian Americans have the ability to pass for a range of ethnic identities in America, including Jewish, Latino, or Greek, self-identified guidos use the signifiers of their subculture as a way to make their ethnic identity visible and unambiguous to those outside of the subculture. Thus, guidos are different from many other ethnic subcultures in that style is used to highlight and emphasize ethnic differences, rather than to escape from their presumed constraints (Thornton).

The guido subculture in its current form can be traced back to various Italian American street gangs from the 1950s and 1960s, such as the Golden Guineas, Fordham Baldies, Pigtown Boys, Italian Sand Street Angels, and the Corona Dukes, among others, who hailed from the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn (Tricarico “Youth Culture” 49). Many of these gangs were under the tutelage of the local Mafia, who organized youth into crews and put them to work. However, much like the 1970s African American, urban, youth gangs that sublimated some of the more violent aspects of their subculture into prosocial avenues such as rapping, break dancing, and graffiti art, over time the violent activities of Italian American youth gangs were translated into purely stylistic concerns (Tricarico “Guido” 48).

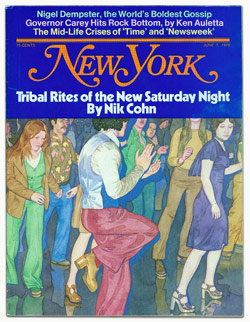

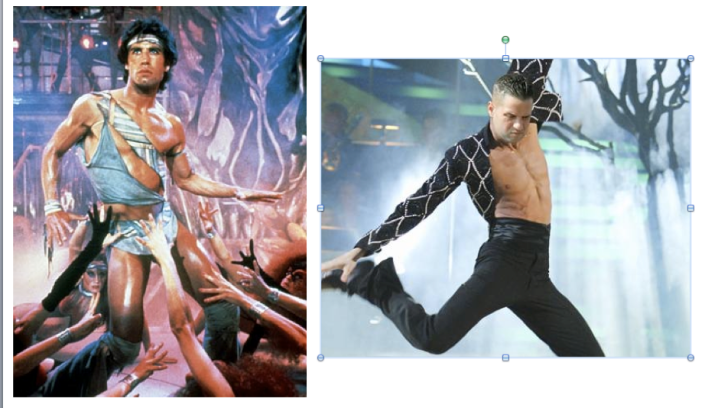

Then, in 1976, British rock journalist Nick Cohn published “Tribal Rights of the New Saturday Night” in New York Magazine. The article follows a young Italian American named Vincent who spends his days working a “9 to 5 job” in a hardware store and his Saturday nights in the disco clubs of New York City. Cohn describes the regimented life of Vincent and his peers in the following way: “graduates, looks for a job, saves and plans. Endures. And once a week, on Saturday night, its one great moment of release, it explodes.”

The article, which was the inspiration for the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, serves as the origin myth for the modern guido subculture. The article and film showcased how working class Italian American youths escaped the tedium of their cramped apartments and restricted finances by participating in the glamorous, fantasy world of Manhatttan’s disco clubs.What is most fascinating about this elaborate origin myth is that 20 years later Nik Cohn admitted that, facing pressure to come up with a story about American discos–he made his story up. He based Vincent not on any actual Italian American but on a Mod he knew back in England (Sternbergh).

Indeed, like the Mods of 1960s England, American guidos generally hail from the working classes, and are preoccupied with fashion, music, dancing, and consumerism. Within the Mod subculture, it was acceptable, even mandatory, for men to be fastidious and vain about their clothing — usually expensive, well-tailored suits — and hair (Hebdige 54). In fact, these stereotypically “feminine” interests became “masculine” within the context of the Mod subculture. Similarly, the signifiers of the male guido—gelled hair, earrings, decorative, form-fitting T-shirts and jeans, and even lip gloss—are gendered as masculine, not feminine, within the confines of their subculture.