Introducing Nota Bene # 1: FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS SERIES FINALE

I have a lot of respect for media studies bloggers who are able to supply a seemingly endless feed of quality content to their blogs. I am also envious of their industriousness. Although I would like to post more frequently to my blog other responsibilities, including: caring for and feeding the pet humans, torturing my students, completing committee work, meeting external writing deadlines, folding endless piles of laundry, caring for and feeding my pet animals, exercising, watching Top Chef: Texas, and occasionally exchanging communicative grunts with my husband (yes, in that order), usually keep me from doing so. Whenever a bright idea for a post (or what I think is a bright idea for a post) comes to mind, I scribble it down on a Post It note and begin mentally composing it as I wipe my toddler’s rear end or fold socks. But more often than not those Post It note ideas (and the long form posts I compose in my head) end up in the trash when I realize that a week has passed and no one will now care what I thought of the Boardwalk Empire season finale (I thought it was kickass, for the record).

So I think I’ve come up with a solution to the workingmotherblogger’s problem. In addition to my regular blog posts, which often range from 1,000 to 2,000 words, I am introducing a new feature to my blog: the Nota Bene. Nota bene is a Latin word meaning “note well.” In legal writing, the term is used to refer to a detail of the document that has been expanded or highlighted. It draws the reader’s attention away from the main topic in order to address a specific issue in greater depth. Very often my frantic Post It scribbles are little details I want to call to the attention of my readers. But during busy times I don’t have several hours to devote to a full-length blog post. So I write nothing. And when I write nothing, I get itchy. Like a sneeze that is about to happen but never does. Or an itch in between my shoulder blades that I just can’t reach. The Nota Bene will be my attempt to scratch those little itches and sneeze those little sneezes. I hope that these shorter, more frequent posts will generate discussion, amusement, or at the very least, a “Bless you, dear!” Below is my first Nota Bene. Consider my itch scratched:

I know that most die-hard fans of Friday Night Lights, the tear-jerking, sweet-but-never-too-sweet TV series about high school football in Texas, watched the final episode way back in February 2011 when it completed its run on Direct TV. Or they watched it when it completed its run on NBC back in April of 2011. OR, they watched it when the final season was released on DVD, also in April of 2011. But I’ve been busy (see the italicized introduction above for a sampling of my daily schedule). My husband and I finally got around to finishing Season 5 last week. And as my time with Coach Taylor drew to a close, I couldn’t help but think about some of the key truths of the series that were highlighted in the final season:

1. Coach Taylor is always right.

Think Coach Taylor’s 80s-style Oakley sunglasses are stupid? Wrong. They’re awesome. Think you’d rather smoke pot all day and dance to Grateful Dead music around camp fires, Hastings Ruckle? Wrong. You should be playing football for the East Dillon Lions (for more on this see Point 3 below). Think you should get to play in the last big game of the season just because you are the star quarterback of the East Dillon Lions, Vince Howard? Wrong. Sit on the bench and stop showboating. Think you can have sex with busty college freshmen just because you’re the “head TA” for History 101, Derek Bishop? Wrong. Get the hell off of Coach Taylor’s lawn before he does to your face what he just did to your car. And this is just in Season 5. Understand this: Coach is always right. He’s a pillar of moral certainty in an uncertain world. He is my reference point, my anchor. When faced with an ethical issue I ask myself “What would Coach do?” and then I put on my 80s-style Oakley sunglasses, pick up my football, and do the right thing.

2. Mrs. Coach is always up in your business.

Tami Taylor is one busy woman. She has a boy crazy teenage daughter, a toddler, and a husband who is always expecting her to show up to some football booster event in a purty dress and high-heeled cowboy boots. Sometimes she is the principal of a high school and sometimes she is a guidance counselor and sometimes she is a women’s volleyball coach. Eventually, she becomes the Dean of Admissions at FancyPants Liberal Arts College in FancyPants Philadelphia. So you might think that you can smoke cigarettes in the girl’s bathroom and eat Chee-tos for breakfast and have a destined-for-the-pole name like Epic, and Mrs. Coach won’t notice because she is too busy coaching volleyball or breastfeeding little Gracie Bell or making sure her hair always falls in those gorgeous, thick curls. But rest assured, troubled youth, Tami Taylor will find you and she will get up in your business. Don’t fight it. Just be grateful for her attention. She’s awesome.

3. Everyone loves football/ football makes you a better person.

Landry Clarke was a studious nerd who founded an alternarock band called Crucifictorious and mocked his best buddy, Matt Saracen, for trying out for the football team. Vince Howard was a petty criminal with no respect for authority and no discipline. Buddy Junior was a disaffected slacker who thought every activity, other than eating and getting drunk, was stupid (he’s right, by the way). But, if you put a football in the hands of these young men, they are suddenly converted into determined, authority-fearing, irony-deficient soldiers of Taylor. Football is that powerful, people.

4. Jason Street, whether he is on screen for 5 seconds or 50 minutes, will break your heart.

Jason Street was paralyzed in the first episode of Friday Night Lights. He left the series in season 3. But every time he returns for a cameo, however short, I cry. In fact, I teared up just searching for photos of Jason Street on Google. Why, Jason, why did it have to happen to you? You coulda been a contender!

5. Julie Taylor is boy crazy.

Julie Taylor has a loving, no-nonsense Daddy and a Mama who is always up in her business. But she also has giant boobs and very full, pouty lips that make Head TAs go cray-cray. Here’s hoping that boring Matt Saracen and his line drawings of hands and outrageously large studio apartment in Chicago can keep those pouty lips satisfied. But my bet is no. There are loads of horny Head TAs in Chicago.

6. Tim Riggins.

Tim Riggins had sex with his paralyzed best friend’s best girl and you forgave him. Tim Riggins drinks beer for breakfast. Tim Riggins has Daddy issues. Tim Riggins does not tell jokes. Tim Riggins will take you to Mexico for experimental spinal surgery. Tim Riggins squints his eyes and looks off into the middle distance better than any other character on television. Tim Riggins will have sex with older women. Tim Riggins will be a father figure to your fatherless son. Tim Riggins has Mommy issues. Tim Riggins will go to jail so that you can have a better life. Tim Riggins must always be addressed as either “Tim Riggins” or “Riggins.” “Who is Tim?” asks Tim Riggins. Tim Riggins will build his own house. Tim Riggins loves football and Texas. Tim Riggins might just love you if he met you. But Tim Riggins isn’t real. Tim Riggins is a character on Friday Night Lights. Pretend I didn’t just write that. Tim Riggins IS real. And I love Tim Riggins. And Tim Riggins loves me. Now leave me and Tim Riggins alone. We’re having beer for breakfast. Mmmm, Riggins.

So what am I missing? What other key truths have I missed? Discuss below.

I Can Haz Nyan Cat?

The other day I was reading an article a friend of mine (Melisser, this is ALL your fault) shared on Facebook. The article, “The 50 Greatest Internet Memes of 2011,” is, as you might imagine, a deep wormhole. Not only is the article long (it covers, in detail, 50 different internet memes), but it includes links to various iterations of these popular memes. It took me almost an hour to get through the first five. Afterwards I cursed myself for wasting precious grading time. When you pay other people to take care of your children so that you can work, wasting an hour on nonsense is unacceptable.

The real question here is not why did I spend a precious hour of my work day reviewing the top internet memes of 2011. Clearly, Hipster Cop and Paula Deen riding things are awesome. But why are they awesome?

Given the rampant popularity of internet memes, it should not be surprising that there is a growing body of work on the subject. Memes are not simply photoshopped images shared on social media and on Internet clip shows for the amusement of those of us who spend long periods of time sitting in front of a computer each day. They form our social and cultural networks. The term “meme” (short for “mimeme”) dates back to Richard Dawkin’s book The Selfish Gene (1976). He refers to memes as “units of cultural transmission.” For example, if I read an article detailing a new approach to say, the critical analysis of widgets, I might mention it to my colleague, an analytical widget specialist. She might then write about it in a paper that she plans to deliver at the National Association for the Critical Analysis of Widgets (aka, NACAW). In turn, people sitting in the NACAW audience, listening to my colleague deliver her paper, will hear that idea, putting it to other purposes, in a variety contexts. The idea spreads as it multiplies. In this way, Dawkins argues, memes are like viruses:

When you plant a fertile meme in my mind you literally parasitize my brain, turning it into a vehicle for the meme’s propagation in just the way that a virus may parasitize the genetic mechanism of a host cell. (192)

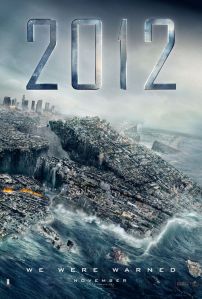

This sounds a little bit like the zombie apocalypse but you won’t need to worry about that for at least 3 more years. Let’s move on, shall we?

Like zombies, we shouldn’t think of memes simply as the innocuous debris of popular culture. As Karl Hodge explains in a article for The Guardian, written all the way back in 2000:

[Memes] are much more than just whispers being passed down a line. Religion and ritual are memes, as are fashions, political ideas and moral codes.

They are copied from one person to the next, planting fundamental beliefs and values that gain more authority with each new host. Memes are the very building blocks of culture. Not every meme is a big idea, but any meme with the right stuff can go global once it hits the internet.

In “‘ALL YOUR CHOCOLATE RAIN ARE BELONG TO US’?: Viral Video, YouTube and the Dynamics of Participatory Culture,” Jean Burgess argues that internet memes are “a medium of social connection.” The value of any particular meme is based on its ability to generate more content, that is, on its “spreadability.” Burgess explains:

…in order to endow the metaphors implied by terms like “memes,” “viruses,” and “spreadability‘ with any explanatory power, it is necessary to see videos as mediators of ideas that are taken up in practice within social networks, not as discrete texts that are produced in one place and then are later consumed somewhere else by isolated individuals or unwitting masses. These ideas are propagated by being taken up and used in new works, in new ways, and therefore are transformed on each iteration – a “copy the instructions,” rather than “copy the product” model of replication and variation.

Indeed, the Paula Deen Riding Things meme offers potential meme participants an actual template to use, promising “anyone can do it”:

For me, at least, community is a major part of the appeal of most internet memes. When I see Paula Deen riding the balloon from the “balloon boy” hoax of 2009, I am delighted because 1) the image itself is funny and 2) because I know that the author of that content also found that image to be funny. The creator and I are linked by our shared laugh over the image of a tipsy Paula Deen riding a tinfoil balloon. Or how about the person who dressed up as Paula Deen Riding Things for Halloween and then herself became an example of Paula Deen Riding Things? When I look at this image I am delighted to think that there are other people who laughed as hard at this image as I did. Just like film genres, internet memes create a sense of community.

But the point of this blog post is not to explain what memes are or how they work, since there are many superior scholars handling those questions (see Works Cited for a few). What I am interested in is why internet memes make me laugh. Dissecting humor is no fun but I am consistently amazed by how funny certain memes become for me and by their ability to make me laugh out loud when I’m sitting alone at my computer. That’s a weird feeling. The memes that make me laugh the most have a few recurring traits:

Recognizability

The majority of memes rely on the recognizability of the image or video that is transmitted from user to user. If you cannot instantly see the resemblance between the meme and its source text (whether that source is something “in real life” or another meme), then the humor won’t work. For example, the humor of the amazing Pepper Spray Cop meme was based primarily on the recognizability of its source: the horrific police brutality that took place at a peaceful UC Davis student protest. This story was all over the news — particularly online — and the various YouTube videos documenting the protest have racked of millions and millions of views.

This meme is particularly interesting because its source text is incredibly disturbing, revealing the casual way in which someone in power is able to use a weapon of suppression on a peaceful citizen. But the meme’s power relies precisely on the viewer’s ability to register all of this tragedy, to recognize the new environment into which Pepper Spray Cop has been inserted, and to find humor in the very incongruity of their meeting. For this reason, I think the best examples of this meme are those which have PSC spraying symbols of innocence or peace:

As the old saying goes: comedy = tragedy + time

Repetition

For all four years of college, I worked for the campus humor magazine. Often, in order to meet publisher deadlines, the staff would literally work all night: scanning images, laying out pages, and writing content. The last-minute content was almost always the product of delirium and repetition. What was not funny at 9 pm was very, very funny by 3 am. It’s all about the repetition: if say something unfunny often enough, eventually it will be funny. Even Henri Bergson knows that repetition is awesome, or so he says in his essay “Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of Comic.” He offers this example:

The same by-play occurs in the Malade Imaginaire. Through the mouth of Monsieur Purgon the outraged medical profession pours out its vials of wrath upon Argan, threatening him with every disease that flesh is heir to. And every time Argan rises from his seat, as though to silence Purgon, the latter disappears for a moment, being, as it were, thrust back into the wings; then, as though Impelled by a spring, he rebounds on to the stage with a fresh curse on his lips. The self-same exclamation: “Monsieur Purgon!” recurs at regular beats, and, as it were, marks the TEMPO of this little scene.

Let us scrutinise more closely the image of the spring which is bent, released, and bent again. Let us disentangle its central element, and we shall hit upon one of the usual processes of classic comedy–REPETITION.

I think, had Bergson has the opportunity to see the Nyan cat video, he would be using that as an example, rather than Moliere. Watch the following videos and I think you’ll agree. First, take a look at the original Nyan cat. You only need to watch it for about 30 seconds to get the point:

Then, there are Nyan cat videos which play with Nyan’s presumed ethnicity. This variation on the meme adds stereotypical signifiers of an identity — such as a turban and Bollywood music — to the source text:

There are versions of the Nyan cat meme that simply play with its addictive, seizure-inducing score:

Then there are the many Nyan cat videos that play with the Nyan cat’s presumed joie de vivre:

This one comes with an important warning “Eats Souls.” Please proceed with caution.

I had to stop watching this one around the 20 second mark:

And finally, Nyan IRL:

With every video I laugh harder until there are literally tears coming down my cheeks as I watch the still image of a cat with a pop tart tied to its back and a plastic rainbow placed next to its ass.

Cruelty

It is difficult to deny that part of the humor of many internet memes lies in mocking the source text. And it is always a relief to laugh at someone else since it means, for the time being, no one is laughing at you:

I don’t feel all that bad for celebrities who become memes or even “civilians” like Rebecca Black. I think if you put a video on YouTube in the hopes that it will make you famous, then you have to accept the consequences of “fame,” whatever form that fame might take. But I do feel bad for those unfortunate souls who did not intend to be on the internet but caught the snarky eye of a someone with access to Photoshop and WiFi (i.e., everyone):

This meme, Angry Vancouver Fan/Angry Asian Rioter, is particularly mean-spirited. I agree that rioting after a hockey game is stupid. Who watches hockey? But clearly the appeal of this image is who is doing the stupid rioting. Asians as well as Canadians are stereotyped as being mild-tempered pacifists (which is actually a stereotype worth embracing), and so this image appears especially outrageous. “How can this Asian Canadian young man have so much rage?” the internet wonders, “Let’s torture him for it!” Images like the one above remind me of a John Hughes movie: Angry Asian Rioter is Duckie and all of us on the internet are James Spader.

Self Loathing

Sometimes the source text being mocked is the person sitting in front of the computer. For example, the “first world problems” or “white whines” meme that was so popular throughout 2011 mocks the idea that anyone living in a first world country and/or anyone who is white would have a legitimate reason to complain about their life:

In particular, this meme mocks individuals who use social media like Twitter or Facebook to lament the small inconveniences in their otherwise cushy lives, like finding pickles on your sandwich after you said “no pickles.” On the one hand, this mockery is deserved — with so much suffering in the world, is it legitimate to curse your cable provider for creating a DVR incapable of consistently recording the TV shows you program it to record? Sure. But next to famine and oil spills, not so much. The snark is well-deserved and as someone guilty of complaining about many first world problems, I recognize myself in this meme. I especially enjoy cursing my cable provider (you know who are. YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE). This kind of meme serves a valuable social purpose — it forces many of us (or pretty much anyone who regularly consumes and distributes memes) to recognize our own privilege. The best humor holds up a mirror to society.

But let me add a brief sidenote to this “self loathing” aspect of memes. Consider the reaction to the consumer debacle that was Black Friday 2011. The image of people using pepper spray (pepper spray is having the best year EVER!) and guns in order to save a few dollars on their Christmas purchases, is disdainful. And memes like this one appeared:

And a non-comical one:

Both images paint the Black Friday shoppers as greedy, mindless consumers. And yet, should we really be shaming all of those people who stood in lines at midnight, hoping to snag a good deal? In America’s current, desperate economic climate, can we really mock those individuals who plot, plan and scheme to save money during what is the most expensive time of year? Sure, scrambling for a Barbie doll when little children (and adults and teenagers) in Africa are starving feels unreal. But for the unemployed and underemployed worried about putting a present under the tree, waiting on line for a cheap Barbie doesn’t seem so greedy or mindless.

But still, I mean, first world problems, people, first world problems.

Or Just Read this Flow Chart

Cracked.com also did an amazing job of explaining the humor of memes with this elaborate flow chart. I suppose you could have just clicked on this link and skipped my entire post. Yeah, sorry about that.

*****

So, what are some of your favorite memes and why do they make you laugh? I think you know what mine is, at least for this week:

Works Cited

Bergson, Henri. Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of Comic. Mineola: Dover Publications, 1911. http://www.authorama.com/laughter-1.html

Burgess, Jean. “‘ALL YOUR CHOCOLATE RAIN ARE BELONG TO US’?: Viral Video, YouTube and the Dynamics of Participatory Culture.” Video Vortex Reader: Responses to YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures. 101-109.

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

So, What’s Your Book About Anyway? (aka, Blatant Self Promotion)

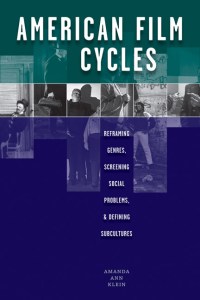

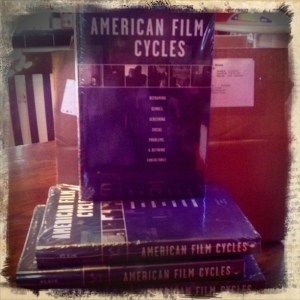

Late last month a small cardboard box arrived at my office at work. In it were ten shrink-wrapped copies of my very first book, American Film Cycles: Reframing Genres, Screening Social Problems, & Defining Subcultures. Long title, eh? (more on that later). I was so delighted by the arrival of this long-awaited package that I posted a picture to my Facebook account:

Throughout the long process of writing my book proposal, revising and cutting down a 400 + page dissertation to a 200 page book, compiling my own index (DON’T DO IT!), and checking my proofs, I would often post book-related status updates on Facebook. Therefore, when I posted the above image, most of my Facebook friends understood that this was the culmination of many years of hard work (seven years, if you count the years it took to write the dissertation). I received hearty congratulations and words of support. It felt wonderful, like being the Prom Queen. Or at least that’s how I imagine being the Prom Queen would feel.

However, it is an odd thing publishing an academic book. On the one hand, my colleagues at East Carolina University, my graduate school professors and friends, and the other academics I have met along the way have a very clear idea about how difficult it is to obtain a book contract with a university press, how this will be a boon to my tenure case (fingers crossed), and finally, how specialized the audience is for a book like this. In other words, although my mother has purchased copies of this book for each of my aunts and uncles, I am fairly certain that my aunts and uncles are going to stop reading my book around page 2. That is, if they even crack it open at all.

My aunts and uncles will stop reading not because my book is difficult to understand or filled with field-specific jargon. Quite the contrary, I try to write as I speak: simply and directly (minus the occasional curse words). I think my relatives will not read my book because academic books are peculiar creatures. Generally, academic books are a dissection of a very specific idea or question in a very specific field of study. And unless you are somewhat interested in that idea/question, you probably won’t enjoy reading an academic book. It has nothing to do with the intelligence of the reader or the accessibility of the book — if you aren’t interested in the subject, academic books can be … monotonous.

If my wonderful editor over at the University of Texas Press is reading this post right now, I am betting smoke is coming out of his ears “Why are you discouraging people from buying your book?!?” I guess my fear is that my dear friends and family, who only bought American Film Cycles because I wrote it (as opposed to an interest in the topic), will open it up and realize that they spent $55 on a pretty blue paperweight. Can you tell that I have a guilt complex?

In order to both combat this guilt and promote my book at the same time, I’ve decided to write a blog outlining the subject and purpose of American Film Cycles. Then, if you buy it and you’re bored it’s your fault, isn’t it? So below I offer some FAQs about my book (and by “Frequently Asked Questions” I mean, “the questions I just made up right now”):

FAQs about American Film Cycles

Why did you write this book?

The point of my book is to offer the first comprehensive discussion of the American film cycle.

What is a film cycle?

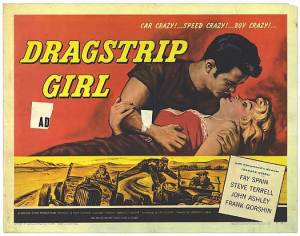

Film cycles are a series of films associated with each other due to shared images, characters, plots, or themes. Film cycles usually form based on the success of a single, originary film. The images, characters, plots, or themes of that successful film are replicated over and over until the audience is no longer paying to see these films. Then the studio producing these films has to either alter the original formula or abandon it all together.

That sounds a lot like a film genre. Say, what are you trying to pull here, lady?

I know, they do sound a lot alike. But they’re different. Trust me. Film genres and film cycles generally form for the same reasons: a particular combination of image and theme resonates with a particular audience. However, cycles differ from genres when it comes to a few things, which I’ll briefly discuss below:

1. topicality: A film cycle needs to repeat the same images and plots over and over within a relatively short period of time (most cycles only “live” for 5-10 years). A cycle must capitalize on the contemporary audience’s interest in a subject before it moves on to something else (for example, the torture porn cycle that was extremely popular just a few years ago). While individual films within a genre may be quite topical (see, for example, how the gangster genre has altered the ethnicity and race of its hero over the decades to fit America’s changing view on who or what is “the public enemy”), film cycles are defined by their topicality.

2. longevity: One major difference between film cycles and film genres is that genres can better withstand interludes of audience apathy, exhaustion, or annoyance. Westerns, to name one prominent example, enjoy periods of intense audience interest as well as more fallow periods when audience interest wanes. Why are they able to do this? Simply put, film genres are founded on a large corpus of films that have been existence for decades at a time. The basic syntax or themes of the most established genres address a profound psychological problem affecting their audiences, such as the way gangster films address the legacy and impossibility of the American Dream. Film cycles generally address something far more topical and time-bound.

3. stability: It’s best to quote the master of genre studies, Rick Altman, here:

“The Hollywood genres that have proven most durable are precisely those that have established the most coherent syntax (the Western, the musical); those that disappear the quickest depend on recurring semantic elements, never developing a stable syntax (reporter, catastrophe, and big-caper films to name a few” (39).

Cycles generally lack a stable syntax, or set of themes. They are too new and fleeting to remain stable. Therefore, while film genres are defined by the repetition of key images (their semantics) and themes (their syntax), film cycles are primarily defined by how they are used (their pragmatics).

Huh?

In other words, what separates cycles from genres is their intensely intimate relationship with their audiences and how audiences use them. The metaphor I use in my book is this: “If the relationship between audiences and genre films can be described as a long-term commitment with a protracted history and a deep sense of familiarity, then the audiences’ relationship with the film cycle is analogous to ‘love at first sight'” (11).

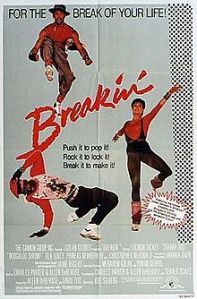

For example, in the 1950s, just as teenagers were starting to view themselves as “teenagers,” film studios tapped into this market by releasing a slew of films that exploited the newly emerging concepts of the teenager, juvenile delinquency, and rock n’ roll. But this relationship wasn’t one-sided. As much as studios exploited the teen subculture for profit, the teen subculture needed these films. Studios were integral to the definition and formation of this youth subculture, with their economic motivations acting as a catalyst, rather than a deterrent, for the growth of the subculture.

Why is your title so long?

I love short academic book titles.I think my all-time favorite title is by Richard Dyer: White: Essays on Race and Culture (the book itself is pretty damn amazing too). I wanted something similarly short and pithy for my book as well, because as we know, academic book titles and article titles can get out of control. However, after numerous back-and-forth e-mails with my infinitely patient editor, he convinced me that the more keywords that appear in my title, the easier it will be for interested readers to find my book. I think he’s right.

Okay, I understand. But so what?

In my book I argue that cycle studies offers an important compliment to traditional genre studies by questioning how generic structures have been researched, defined, and understood. Cycle studies’ focus on cinema’s use value—the way that filmmakers, audiences, film reviewers, advertisements, and cultural discourses interact with and impact the film text—offers a more pragmatic, localized approach to genre history in particular and film history in general. Cycle studies argue that films are significant not so much because of what they are, but because of why they were made, why studios believed that they were a smart investment, why audiences went to see them, and why they eventually stopped being produced. Any film or film cycle, no matter its budget or subject matter, has the potential to reveal a wealth of information about the studio that made it and the audience who went to see it. In my book I liken film cycles to fossils. Pressed on all sides by history/popular culture/audience desires/studio’s economic motivations/trends in fashion/trends in music/ etc. , film cycles serve as documents forever preserving a particular moment. In other words, if we examine film cycles (and film studies has, for the most part, entirely ignored this important production strategy), we can learn a lot about how audiences interact with films and how films interact with audiences.

In my book I argue that cycle studies offers an important compliment to traditional genre studies by questioning how generic structures have been researched, defined, and understood. Cycle studies’ focus on cinema’s use value—the way that filmmakers, audiences, film reviewers, advertisements, and cultural discourses interact with and impact the film text—offers a more pragmatic, localized approach to genre history in particular and film history in general. Cycle studies argue that films are significant not so much because of what they are, but because of why they were made, why studios believed that they were a smart investment, why audiences went to see them, and why they eventually stopped being produced. Any film or film cycle, no matter its budget or subject matter, has the potential to reveal a wealth of information about the studio that made it and the audience who went to see it. In my book I liken film cycles to fossils. Pressed on all sides by history/popular culture/audience desires/studio’s economic motivations/trends in fashion/trends in music/ etc. , film cycles serve as documents forever preserving a particular moment. In other words, if we examine film cycles (and film studies has, for the most part, entirely ignored this important production strategy), we can learn a lot about how audiences interact with films and how films interact with audiences.

On a practical level, cycle studies can answer a question I am so often asked by students and friends “Ugh, why do they keep making movies about [insert annoying film cycle subject here]?” Well, friends, after seven long years of research, writing, and revision, I think I can answer that.

So there you have it, folks. If you have read all of this and are still interested in my (AMAZING! GROUNDBREAKING! LIFE CHANGING!) book, you can purchase it here or here (it’s cheaper through the press). Or, you can order one for your university’s library. Or you can order 10 copies, sew them together, and make yourself a nice book coat. It’s cold out there — knowledge is warm.

Works Cited

Altman, Rick. “A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre.” Film Genre Reader III. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007. 27-41.

Klein, Amanda Ann. American Film Cycles:Reframing Genres, Screening Social Problems, & Defining Subcultures. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011.

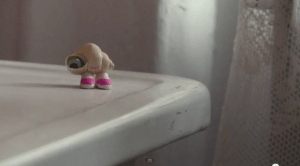

Why I Can’t Stop Watching “Marcel the Shell with Shoes On”

Although I had heard about Jenny Slate and Dean Fleischer-Camps’s stop-motion video, “Marcel the Shell with Shoes On,” over a year ago, it was only after the sequel, “Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, Two,” premiered on YouTube that I finally decided to watch it. Then I watched it again. Then I played it for my kids. Then I sent the video to friends. Then I began to quote it obsessively to myself. Of the two videos, the sequel is the superior text (due to it’s exploration of shell hardship), but both should be watched.

The Original:

Part Two:

The first thing that grabbed me about this video series is its format. Much like popular single-camera television comedies such as Arrested Development, The Office, Parks & Recreation, and Modern Family, “Marcel the Shell with Shoes On” is filmed as if Marcel is the subject of a documentary. Marcel addresses the camera directly, answering questions and pointing out items that appear in his home, such as a pet made out of lint. And like the subjects of The Office and Parks & Recreation, Marcel’s world is profoundly mundane. Nevertheless, Marcel immediately ingratiates himself with the audience because 1. he is an adorable shell wearing tiny adorable shoes and a single googly-eye and 2. Marcel has a nasaly, childlike (or should I say shell-like?) voice, courtesy of Jenny Slate. The fragility of Marcel’s shell body and single eye, combined with Slate’s spot-on voice work, make Marcel into an ideal subject for the smallness of the new comedy verité” genre. Like Parks & Recreation‘s Leslie Knope (Amy Poehler), Marcel is both aware of his inconsequentiality and yet, is still proud of who he is and how he lives his life. He is an eternal optimist.

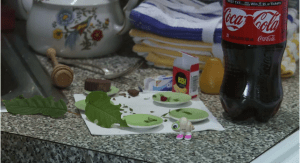

Most of the humor of the series is based on Marcel’s smallness and the way that smallness impacts his ability to function in a world built for large, resilient humans, not tiny shells. He often asks his off-screen interviewer questions that resemble the kind of jokes one five year old tells to another: “Guess what I use for a beanbag chair? A raisin” and “Guess what I do for adventure? I hang glide on a Dorito.” These jokes, silly as they are, paint a picture of Marcel’s tiny world. Furthermore, Marcel is usually filmed in such a way that we see the world from his small perspective. The camera films him at eye-level when he stands on a laptop or book and sits on the floor when Marcel scurries under the leg of chair to avoid his new puppy. This cinematography gives us a sense of how large the world must look to a small shell like Marcel.

However, Marcel seems gleeful, not discouraged, by the limitations of his smallness. His size forces him to be inventive, to tinker with the objects he finds around him and put them to new uses. For example, my favorite bit in the entire series revolves around Marcel’s primary mode of transportation — a bug:

“If you do drive a bug you have to be pretty easy-going because you’re only going to get to go where the bug wants to go. One week there was a maple sugar syrup spill in the kitchen and every time I would ride the bug, no matter where I wanted to go, I would just end up back in the kitchen.”

This anecdote reminds me of a Shel Silverstein poem I read often as a child:

One Inch Tall

If you were only one inch tall, you’d ride a worm to school.

The teardrop of a crying ant would be your swimming pool.

A crumb of cake would be a feast

And last you seven days at least,

A flea would be a frightening beast

If you were one inch tall.If you were only one inch tall, you’d walk beneath the door,

And it would take about a month to get down to the store.

A bit of fluff would be your bed,

You’d swing upon a spider’s thread,

And wear a thimble on your head

If you were one inch tall.You’d surf across the kitchen sink upon a stick of gum.

You couldn’t hug your mama, you’d just have to hug her thumb.

You’d run from people’s feet in fright,

To move a pen would take all night,

(This poem took fourteen years to write–

‘Cause I’m just one inch tall).

As I child I loved Shel Silverstein’s poetry because he managed to capture, in equal parts, the profound joy and the profound terror of being child. Silverstein understood that the child’s imagination is a gift and a burden. Imagination allows children to transport themselves to places that are exciting and wonderful and yet, because of the boundlessness of the imagination, these places can easily become scary. Sure, if you were one inch tall you could surf on a stick of chewing gum. But you would also find full-sized feet terrifying. As a child I always despaired over the line “You couldn’t hug your mama, you’d just have to hug her thumb.” One wonders if Marcel possesses the ability to hug: he has no arms and he’s a shell.

Marcel offers the same mixture of joy, terror, and sadness as any good Silverstein poem. For example, after the aforementioned bug anecdote, Marcel concludes “Really, what you just have to want to do is take a ride.” Here Marcel takes a situation that should be infuriating — a mode of locomotion that cannot be controlled — and makes it into something liberating. Riding a bug is about a willingness to have an adventure — not about reaching a predetermined destination. Likewise, Part Two concludes with the following exchange:

“Guess why I smile a lot?”

“Why?”

“Uh, ’cause it’s worth it.”

This statement would sound hokey in a different context (though I think Leslie Knope could also pull it off). But it is preceded by a shot of Marcel standing on a white countertop, looking offscreen towards a window, as chimes tinkle softly. He takes a deep breath and sighs, then turns to face the camera with this insight. Afterwards, he turns back to face the window, enjoying existence, mundane as it is.

Of course, life for a small shell isn’t all fun and games — it is also plagued with hazards. In Part One Marcel explains how he longs for a dog. In Part Two he gets his wish, though clearly even a small dog is too much for Marcel. In one scene Marcel runs off camera, screaming, after the dog jumps us to bark at the door. And in Part Two, Marcel explains that he once had a sister named Marissa. “What happened to her?” the interviewer asks. “Someone asked her to hold a balloon.” Marcel doesn’t elaborate on what happened after his sister took the balloon. Instead the camera cuts to a new scene in which Marcel discusses his dog’s proclivities (“Look at him: treats and snoozin’, snoozin’ and treats. That’s it”). The subject of Marissa comes up again later in the video, thus making it clear that her loss was not trivial: “It was pretty hard at the time but now I just think ‘Ohhh, you know, she’s travelling.'” Marcel is still mourning the loss of his sister. But he also understands that life is filled with difficulties and tragedies, especially when one is a shell, so it’s best to focus on the small things that bring us happiness. Like wearing lentil hats and having friends over for salad.

Life is hard for a shell. It’s easy to get carried away by a helium balloon, trampled by your own pet dog, or worst of all, ignored. But Marcel enjoys living his life — sleeping “eight to the muffin” in a fancy hotel and reading receipts for pleasure — despite it’s obvious complications. After I showed this video to my daughter this morning I asked her:

“Did you like it?”

“Yes”

“Was it funny?”

“Yes. But it was also sad.”

“Why was it sad?”

“It just was. But it was funny.”

I think this is why I am so captivated by “Marcel the Shell with Shoes On.” It’s difficult to make humor sad and sadness humorous. But Marcel walks that line perfectly. While wearing perfectly tiny pink shoes.

The Myth of the Ugly Duckling

Last year I wrote a blog post detailing my biggest television pet peeves because TV shows are filled with conventions that are used and reused until they drive their audiences nuts. Repetition is part of popular culture. There’s even an entire website devoted to annoying, overused TV tropes. Sure, we must accept the easy shorthand of the TV trope if we are going to watch TV, but ever since I started seeing ads for Zooey Deschanel’s new comedy, New Girl , I’ve been thinking a lot about one particular trope that I’ve always hated. It goes by many names, but for the purposes of this post, let’s call it “the myth of the ugly duckling.” You all read “The Ugly Duckling” when you were a kid, right? First published in 1843 (thanks Wikipedia!), Hans Christian Andersen’s famous story is about an unattractive baby duck who is abused by all who meet him until finally, one glorious day, he realizes that he is actually a beautiful swan! Here’s how Andersen’s story concludes:

He had been persecuted and despised for his ugliness, and now he heard them say he was the most beautiful of all the birds. Even the elder-tree bent down its bows into the water before him, and the sun shone warm and bright. Then he rustled his feathers, curved his slender neck, and cried joyfully, from the depths of his heart, “I never dreamed of such happiness as this, while I was an ugly duckling.”

The lessons in this classic tale are clear: If people bully you based on something you cannot control, such as the fact that you are “ugly,” don’t worry. Eventually, you will be accepted by a group of much better looking people. These people will embrace you and love you based on something else you cannot control, the fact that you are now “beautiful” and look just like them. Good for you, little duck!

Obviously, this message of “beauty as transcendence” is problematic and highly damaging to the psyches of young children and insecure adults alike. But that’s not why I dislike the myth of the ugly duckling. I dislike it, and its many iterations in popular culture, because the ugly duckling is not “ugly.” I mean, have you seen a baby duck (or a baby swan) before? Let me refresh your memory:

Obviously, this message of “beauty as transcendence” is problematic and highly damaging to the psyches of young children and insecure adults alike. But that’s not why I dislike the myth of the ugly duckling. I dislike it, and its many iterations in popular culture, because the ugly duckling is not “ugly.” I mean, have you seen a baby duck (or a baby swan) before? Let me refresh your memory:

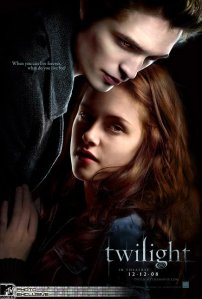

And that’s pretty much the problem I have with the myth of the ugly duckling when it is translated into a film or TV show. It’s simply untrue. Don’t tell me someone is ugly when they are so clearly NOT ugly. My first exposure to this myth, as applied to women, occurred when I was about 6-years-old and watching my favorite channel, MTV:

Thank goodness “Goody Two Shoes” was in heavy rotation in 1982; it communicates so many important lessons about beauty, sexuality, and male-female relationships. The most important lesson Mr. Ant taught me is that women who wear suits, buns, and glasses are highly unattractive. Even when they are so clearly hot. This was upsetting to me because at the time I wore a large pair of glasses, quite similar to the pair worn by the woman featured in the video, and I often wore my hair pulled back. Also, I did not drink or smoke. “Shit,” my 6-year-old self noted, “I’m ugly!”

But not to worry. According to this video, it is easy to capture the attention of the wily Adam Ant. All you need to do is shake your bun out and remove those giant glases. Viola! Ant Ant is totally going to screw your brains out in that hotel room while his horny butler watches through the keyhole. I should also note this video’s plot, about an uptight looking woman who appears to be interviewing Adam Ant, and then decides to let her hair down (literally) and make sweet love to the rockstar, has very little to do with the song’s lyrics. The lyrics themselves (you can read them here), seem to be a critique of image and stardom and of the very transformation the woman makes. But my 6-year-old self was not listening to the lyrics. I was watching the video. And taking copious mental notes.

Fast forward a few years to one of my all-time favorite films, The Breakfast Club (1985, John Hughes). I did not see this film in the theater, but by the time I was in junior high it seemed to be playing on TBS every single Saturday afternoon. Like most kids of my generation, everything I thought I knew about being a teenager came from this film (or some other John Hughes film). Some of the film’s many lessons include: bad boys are sexy, girls who don’t like to make out are prudes, Claire is a “fat girl’s name,” detention is wicked awesome, and, most importantly, if you want cute boys like Emilio Estevez to think you are pretty, stop being so weird and interesting and let the popular girl give you a make over. Ally Sheedy, I am talking to you.

Even as an insecure preteen I noted with dismay that the pre-makeover Allison was actually very, very pretty. After all, she’s played by Ally Sheedy! Ally Sheedy is a fox! Her “make over” doesn’t alter her appearance in any kind of radical way, much as the removal of a bun and glasses doesn’t change much about the goody two shoes in the Adam Ant video. Both of these women were beautiful from the start and the only people who insisted on their physical unattractiveness were the creators of these texts. In other words, almost every ugly duckling I have encountered, dating all the way back to Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, have never truly been “ugly.” Their ugliness is an artifice I have been asked to believe so that the beautiful, swanlike transformation that inevitably follows can happen. Time and again, beautiful women are cast in the role of the “awkward,” “drab,” “dorky,” or “ugly” girl. And all it takes to make them “ugly” is a pair of glasses, a disinterest in fashion, or a quirky hobby.

At this point you might be thinking: so what? Who cares if film and TV audiences are repeatedly asked to view highly attractive women as “ugly”? I guess my problem with all of this is that in these films and television shows I am told, over and over, that certain key signifiers make attractive women into unattractive or undesirable women. These signifiers include but are not limited to:

Being a tomboy and an awesome drummer:

Being poor:

Being Aaron Spelling’s daughter:

Wanting to be an artist:

Having musical talent that far outstrips that of your peers:

Being smart and wearing glasses:

In every case, the decision to be studious or artistic or slightly different from everyone else transforms a woman who would normally have more suitors than an alley cat in heat into a lonely spinster. So the message is: ugly women are screwed. And pretty women who value something other than being pretty are screwed. And if you are ugly and you like to read? Well, start collecting cats and Hummel figurines now because you have a lonely life ahead of you, spinster.

And that is why I could not bring myself to watch the premiere of New Girl. I just could not stand the way that Zooey Deschanel’s character, Jess, was repeatedly described as being “dorky” and “awkward” in press releases and in early reviews. I don’t care how big her glasses are or how often she bursts into song at inopportune times. Zooey Deschanel is not a “dork.” She’s hot. Can a woman who is that beautiful really and truly be a “dork”?Now I’m not saying that hot chicks don’t get dumped, as Deschanel’s character does in the show’s premiere. And I’m not saying that hot chicks don’t find themselves feeling awkward or acting the fool. I am sure they do. But it’s hard to buy a woman like Zooey Deschanel as a true awkward dork. You know who plays good dorks? Kristen Wiig. Someone else? Charlyne Yi. I believe her.

Just not another hot chick in glasses.

It’s time for film and TV to get a new trope. Make a character a social outcast because she’s a bully or because she’s too judgmental. Not because she wears glasses or reads books or carries a big purse. After all, you need a big purse to carry all those books. And you need glasses to read those books. Just sayin.

Premiere Week 2011!

This might come as a shock to those of you who regularly read this blog, but … I love TV. And although the “fall television season” is not what it used to be now that so many television series premiere in the winter and even the summer, there are still plenty of new shows to be excited about. That’s why I volunteered to write some short reviews of two particularly exciting series premieres, The CW’s Ringer and NBC’s Up All Night, over at Antenna.

My short reviews of Ringer (click here) and Up All Night (click here) are live now. If you are simply too lazy to read these 300 word reviews (and I can appreciate that kind of laziness), I will summarize for you: Ringer is a Sarah Michelle Gellar vehicle about twins, mirrors, and identity theft (meh) and Up All Night is a surprising funny comedy about how babies ruin your otherwise super-awesome life (check it out!). There are no vampires in either program. Yep, that bummed me out too.

Performing Gender and Ethnicity on the JERSEY SHORE

This summer I had the good fortune of being accepted to the “Gender Politics and Reality TV” conference hosted by University College Dublin. I knew it would be difficult to attend this conference–it coincided with the first week of classes at the university where I work–and I knew it would be expensive. But I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to attend a small conference that was entirely focused on reality television. I am starting a new research project on MTV-produced reality shows and I thought this conference would help to kickstart my writing and research. So I planned well: I applied for and was awarded an international travel grant to help pay for the expensive trip, I enlisted two wonderful colleagues to teach my first week of classes for me, and I finished my paper and visual presentation a full week ahead of schedule. The night before I was set to fly to Dublin, I was finishing up my packing and it was only then that I thought to take a look at my passport. I had not flown out of the country since 2006 and I had no recollection of when the document was set to expire. It expired in 2008. Ooops.

I won’t describe the panic that followed this realization. I will just say that it took me about 2 hours of phone calls and internet research to conclusively determine that there was absolutely no way for me to get an updated passport in 24 hours (surprise!). I was going to have to cancel my trip to Dublin. I would like to offer a good explanation for why I purchased an international power adapter two weeks before my departure but only thought about my passport — the only way to legally leave my country — 24 hours before my departure. But I don’t have one. To a Type A personality like me, such an oversight is unthinkable. Like Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) in Memento (2000, Christopher Nolan), I have constructed a series of elaborate tricks to ensure that I remember to complete the many tasks required of a full-time working mother of two: alerts on my phone, copious notes in my planner, lists, lists and more lists. But this time, my system failed. Where was my Polaroid photograph? Where was the tattoo, written backwards across my chest, reading “GET PASSPORT RENEWED 4-6 WEEKS BEFORE DEPARTURE“?

There are many reasons why missing this trip was devastating to me: the expensive plane ticket, the embarrassment of contacting the conference organizer (a woman I greatly admire) and explaining what had happened, the loss of a much-needed vacation from my children (I love them, but sometimes Mama needs to get away), the chance to meet and talk shop with reality TV scholars in the context of a small, intimate conference, and the lost opportunity to present my work-in-progess to these experts and get their much-needed feedback. I can’t do much about the first four things, but I can, in fact, do something about the fifth. Although a friend attending the conference offered to read my paper for me and thus ensure that my mistake did not derail my panel (Thanks Jon!), I won’t be there for the conversation that follows. So I’ve decided to post my entire paper here on my blog (minus the clips, because I have yet to upgrade my blog so that I can upload my own clips). If you have an interest in subcultures, gender studies, or reality television, please read my paper below and offer me some feedback. While you do this I’ll be drinking a green beer and dreaming of Ireland…

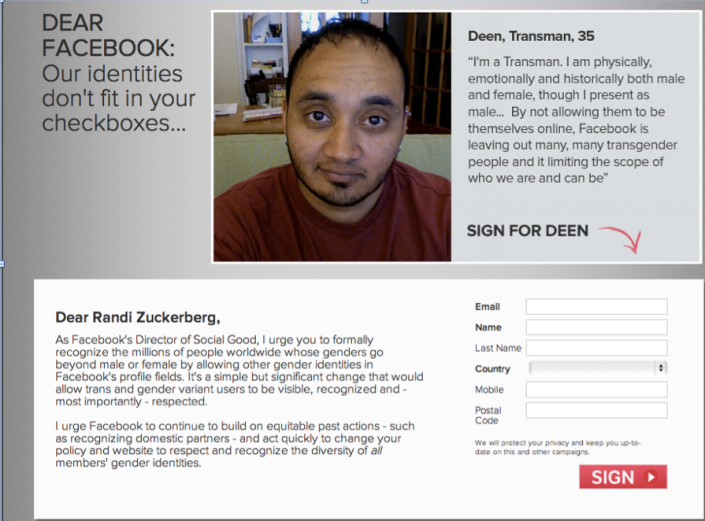

Over the last few weeks an open letter to Randi Zuckerberg, the manager of marketing initiatives at Facebook, was circulated around various social media sites. The letter urges Zuckerbeg to “formally recognize the millions of people worldwide whose genders go beyond male or female by allowing other gender identities in Facebook’s profile fields.” The letter, which also serves as a petition, includes a series of testimonials from Facebook users who believe that the terms “male” and “female” do not accurately reflect their personal experience of gender, where gender is, to quote Robyn R. Warhol, “a process, a performance, an effect of cultural patterning that has always had some relationship to the subject’s ‘sex’ but never a predictable or fixed one” (4).

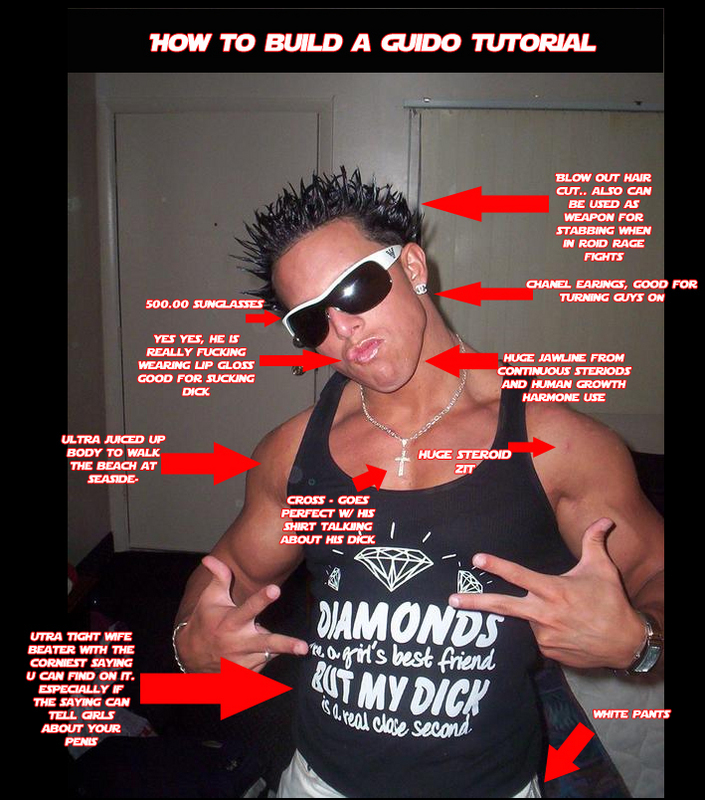

As I read through these testimonials, my mind drifted to MTV’s top-rated reality series, Jersey Shore, as I could imagine one its stars, Pauly D, submitting his own testimonial. If he did, it might go something like this:

“I am a heterosexual man who proudly spends 25 minutes styling my hair. I have earrings in both of my ears and have been known to wear lipgloss. I do not fit into Facebook’s limited gender categories.”

Okay, so Pauly D probably would not write a testimonial about his fluid understanding of gender, but he should. In this paper I argue that the guido identities celebrated in Jersey Shore reconfigure the way gender performs within the context of this Italian American subculture. When men like Pauly D adopt the styles, behaviors, and interests that U.S. culture has enforced as appropriate to women’s bodies, they, paradoxically, feel more like masculine men. In other words, Jersey Shore, for all its misogyny and ethnic stereotyping, actually highlights the performative nature of gender, and how it must be understood as a contingent and multiple process, rather than as a preexisting category (Warhol 5).

Before I go any further, I want to acknowledge that the term “guido” has a troubled history; some factions of the Italian American population see the term as offensive and view Jersey Shore’s cast members as minstrel-show caricatures (Brooks). Other Italian-Americans have reclaimed and reappropriated the moniker as a source of ethnic pride. Still other groups acknowledge that the term exists and therefore seek to understand and unpack its meanings.

My use of the term is neither an endorsement nor a rejection of any of these points-of-view. Instead, I deploy the term “guido” as a way to reference the ethnic subculture that is showcased, celebrated, and derided on Jersey Shore and in the process I hope that I do not cause any offense.

The term guido refers to a specific subcultural identity signified by a series of distinctive clothing styles, music preferences, behavioral patterns, and choices in language and peer groups. This label provides coherence and a solid ethnic character to a set of stylistic choices — including a preference for big muscles, gelled hair and tanned skin — selected by this particular youth subculture. Sociologist Donald Tricarico argues that the term guido denotes a way of being Italian that is linked to an ensemble of youth culture signifiers. He writes: “To this extent, ethnicity also draws boundaries intended to include some and exclude others. It establishes parameters for stylized performances in the competition for scarce youth culture rewards” (“Youth Culture” 38). In addition to the usual rewards of peer acceptance and recognition as a member of the subculture, embracing the signifiers of the guido subculture provides the Jersey Shore’s cast members with fame, money, and lucrative business opportunities. And because MTV provides such powerful incentives for Jersey Shore cast members to perform their ethnicity on national television, MTV’s cameras artificially inflate the signifiers of the subculture. Thus, Jersey Shore becomes a unique opportunity to analyze the performative nature of gender within the framework of an ethnic subculture. In this context “performative” does not just refer to gender as a performance; I am also using the term as a way of understanding, to quote Warhol again, “the body not as the location where gender and affect are expressed, but rather as the medium through which they come into being” (10). In Jersey Shore, gender performs in a unique way in that behaviors typically coded as effeminate actually constitute—rather than negate—masculinity.

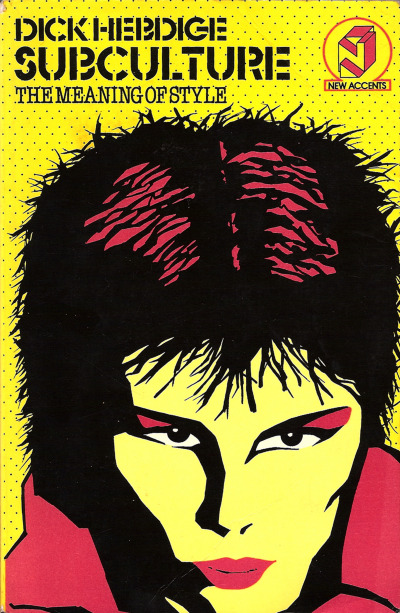

According to Dick Hebdige, every youth subculture represents “a different handling of the ‘raw material of social existence’” (80). While subcultures represent countercurrents within the larger hegemonic structures of society, they are nevertheless “magical solutions” to lived contradictions. In other words, although subcultures initially pose a “symbolic challenge to a symbolic order,” these subcultures are inevitably, almost instantaneously, recuperated into the very system they are supposedly challenging (Grossberg 29). According to Tricarico, the guido “neither embraces traditional Italian culture nor repudiates ethnicity in identifying with American culture. Rather it reconciles ethnic Italian ancestry with popular American culture by elaborating a youth style that is an interplay of ethnicity and youth cultural meanings” (“Guido” 42). Because Italian Americans have the ability to pass for a range of ethnic identities in America, including Jewish, Latino, or Greek, self-identified guidos use the signifiers of their subculture as a way to make their ethnic identity visible and unambiguous to those outside of the subculture. Thus, guidos are different from many other ethnic subcultures in that style is used to highlight and emphasize ethnic differences, rather than to escape from their presumed constraints (Thornton).

The guido subculture in its current form can be traced back to various Italian American street gangs from the 1950s and 1960s, such as the Golden Guineas, Fordham Baldies, Pigtown Boys, Italian Sand Street Angels, and the Corona Dukes, among others, who hailed from the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn (Tricarico “Youth Culture” 49). Many of these gangs were under the tutelage of the local Mafia, who organized youth into crews and put them to work. However, much like the 1970s African American, urban, youth gangs that sublimated some of the more violent aspects of their subculture into prosocial avenues such as rapping, break dancing, and graffiti art, over time the violent activities of Italian American youth gangs were translated into purely stylistic concerns (Tricarico “Guido” 48).

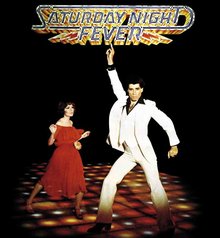

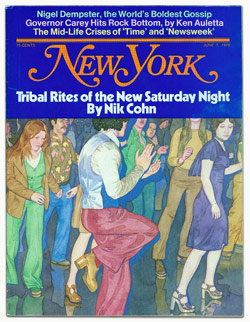

Then, in 1976, British rock journalist Nick Cohn published “Tribal Rights of the New Saturday Night” in New York Magazine. The article follows a young Italian American named Vincent who spends his days working a “9 to 5 job” in a hardware store and his Saturday nights in the disco clubs of New York City. Cohn describes the regimented life of Vincent and his peers in the following way: “graduates, looks for a job, saves and plans. Endures. And once a week, on Saturday night, its one great moment of release, it explodes.”

The article, which was the inspiration for the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, serves as the origin myth for the modern guido subculture. The article and film showcased how working class Italian American youths escaped the tedium of their cramped apartments and restricted finances by participating in the glamorous, fantasy world of Manhatttan’s disco clubs.What is most fascinating about this elaborate origin myth is that 20 years later Nik Cohn admitted that, facing pressure to come up with a story about American discos–he made his story up. He based Vincent not on any actual Italian American but on a Mod he knew back in England (Sternbergh).

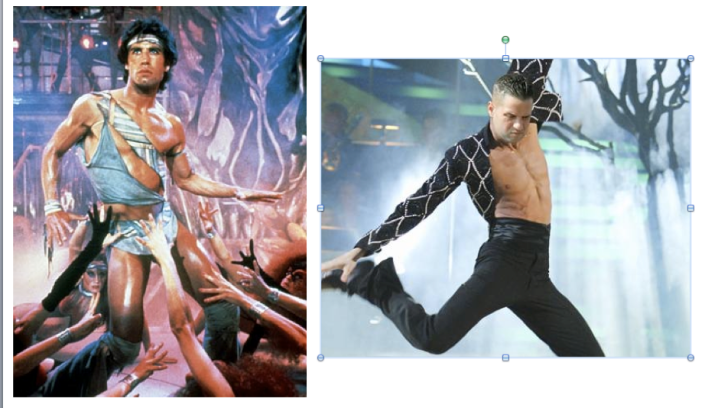

Indeed, like the Mods of 1960s England, American guidos generally hail from the working classes, and are preoccupied with fashion, music, dancing, and consumerism. Within the Mod subculture, it was acceptable, even mandatory, for men to be fastidious and vain about their clothing — usually expensive, well-tailored suits — and hair (Hebdige 54). In fact, these stereotypically “feminine” interests became “masculine” within the context of the Mod subculture. Similarly, the signifiers of the male guido—gelled hair, earrings, decorative, form-fitting T-shirts and jeans, and even lip gloss—are gendered as masculine, not feminine, within the confines of their subculture.

Pauly D’s elaborate hair regiment and Mike Sorrentino’s obsession with his abdominal muscles also accord with the Italian concept of “bella figura,” which refers to the practice of “peacocking” or “presenting the best possible appearance at all times and at any cost” (Wilkinson). Bella figura, a concept dating back to the 1400s, means making the best possible presentation of one’s self at all times in order to conceal whatever the individual may otherwise be lacking in looks, money, education, or experience. We can read the contemporary guido’s obsessions with grooming as the fulfillment of bella figura, and thus, as an inherently Italian practice. To spend 25 minutes on your hair is not feminine in Pauly D’s world; rather, it is a signifier of his Italian masculinity. The guido identity therefore allows Italian American males to engage in activities which would normally be coded as feminine, and therefore, off-limits.

Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino is a striking example of the bella figura legacy in the guido subculture. Several Jersey Shore episodes feature scenes in which the roommates must wait for Mike to complete his grooming before they can head out to the club. The editing of these scenes suggests that Mike spends far more time on his appearance than either his male or female roommates do. Mike has also built a reputation for codifying his daily toilette with formal titles, like “Gym, Tan, Laundry.” In addition to his GTL, Mike makes weekly trips to the barbershop for haircuts and eyebrow waxing, all in service of becoming “FTD” or “fresh to death.” The following Access Hollywood clip demonstrates the performative nature of gender within and outside of the guido subculture.

Click here to watch

For the viewing audience that is not a part of the guido subculture, this segment is played for laughs: the joke is that these two muscular, heterosexual men are enjoying “feminine” pleasures like facials and hand massages. These gender acts make them appear effeminate to those outside of their subculture. However, for Mike, Pauly D, and other members of their subculture, grooming is what makes them masculine. Judith Butler explains this more elegantly: “As performance which is performative, gender is an ‘act,’ broadly construed, which constructs the social fiction of its own psychological interiority” (399).

Vinny provides another useful example of gender performativity in Jersey Shore. In the series premiere, Vinny, who calls himself a “mama’s boy” and a “generational Italian,” immediately distances himself from the stylistic trappings of the guido subculture, explaining “The guys with the blow outs, the fake tans, that wear lip gloss and make up…those aren’t guidos, those are f**king retards!” Although he claims to prefer stereotypically masculine activities like playing pool and basketball over “GTL,” throughout Season 1 Vinny is coded as the least masculine male cast member in the house. While other male cast members regularly become embroiled in fistfights and bring home a new sexual conquest every night, Vinny distances himself from these stereotypically aggressive male behaviors. He is the resident “nice guy.”

This sensitive persona shifts markedly in Season 3, however, when Vinny is pressured by his male housemates to get both of his ears pierced with a pair of diamond studs. In the context of American culture, getting both ears pierced, especially with diamonds, is a style choice associated with women and femininity. However, the Jersey Shore cast equates this gender act with masculinity and treats the event itself as a male rite of passage. For example, when Vinny agrees to get his ears pierced, Pauly D exclaims “My boy’s becoming a man!” Later, in his confessional interview, Vinny explains that he endured the pain of the ear-piercing “like a G.” Thus, not only is double ear-piercing considered masculine within the guido subculture–withstanding the pain of this important ritual is equated with being a violent, cocksure gangster, the ultimate signifier of American masculinity. Once the piercing is complete, Pauly and Ronnie delight in the results like two proud parents. They even ask Vinny if he “feels different,” much as mothers ask their daughters if they “feel different” after getting their first menstrual period.

Vinny does not pierce his ears because he is a man; he becomes a man through the act of piecing his ears. In other words gender acts that are coded as feminine outside of the guido subculture actualize and activate Vinny’s sense of himself as a man within the subculture. The contradiction between the nature of these behaviors and the gender they perform highlights the contingent nature of gender itself. So how does Vinny act now that he has finally “become a man”? In addition to, in his own words, “walking with a gangster limp” and wearing his baseball cap at a “gangster lean,” his newly-pierced ears compel Vinny to go after women like a dog in heat. At the club that evening, the normally polite, somewhat shy reality TV star dismisses the women who approach him for not being attractive enough. Later, after his attempt at coitus with a woman from the club fails, Vinnie turns to Snooki, his roommate and occasional lover, for a quick tryst. When Snooki dismisses Vinny’s advances as offensive, the newly masculinized Vinny picks up his small conquest and attempts to drag her into his bedroom. Vinnie’s roommates marvel at his uncharacteristically aggressive behavior and tellingly attribute it to his new earrings. Here, subcultural style “empowers” Vinnie to indulge in the stereotypes of masculine behavior that he has previously avoided.

Earlier I mentioned that the male guido’s, obsession with grooming and style has come to stand in for the violence that this immigrant group once needed to deploy in order to survive. The male guido’s attention to his toilette, an affectation generally associated with effeminacy, stands in for the stereotypically masculine behaviors of fighting, killing, and defending one’s home turf that have been rendered superfluous in contemporary society. Thus, if being physically strong was once a prerequisite for membership in a street gang in order to defend oneself from outsider attacks, a muscular physique is now an end in itself; it is what makes Mike “feel like a real man.” But what creates femininity within this subculture? The answer to this question is more complicated. Certainly, the female guido style is codified: the women must wear their hair long (with the aid of highly flammable hair extensions), and usually dye it dark, in accord with their Italian heritage. Make up must be bright and noticeable, with an emphasis on the eyes, lips, and nails (Tricarico “Guido” 44).

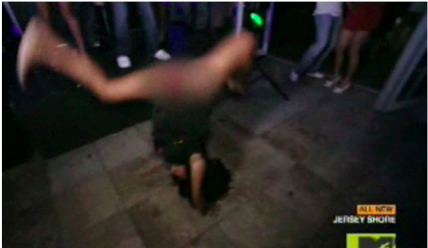

And while it is clear that Snooki, J Woww, Deena and Sammi spend a lot of time on their appearances (after all, Snooki’s pouff doesn’t do itself), far more screen time is devoted to the women’s defiance of femininity. In almost every episode female cast members belch loudly, urinate outside, or vomit on camera, behaviors that are often associated with masculinity or at least with the un-feminine. Deena often falls due to extreme intoxication and on several occasions Snooki has inadvertently exposed her genitals to MTV’s cameras. In other words, the women of the Jersey Shore house are lusty, hungry, messy, and quite comfortable with their own bodily functions.

Perhaps the strongest rejection of traditional female gender roles occurs in the handling of the all-important Sunday night meal. Several Jersey Shore episodes feature a scene in which the roommates sit down to an elaborate Sunday night dinner. In most Italian homes, the matriarch does the shopping, cooking, and cleaning for this traditional, multi-course meal. When, for example, Vinny’s mother visits the house in season one, Pauly D compares her to his own mother, whom he describes as an “old school Italian,” because she cleans the Jersey Shore house after fixing the roommates an extravagant lunch. Despite these defined roles, passed on from one generation of Italian American women to the next, the women of Jersey Shore either ignore or reject these gender expectations. Several scenes in the series are devoted to the women’s refusal to shop, cook or even clean up after house meals. In season 2, Jenni and Snooki agree to cook the Sunday dinner, not out of a sense of responsibility or a desire to nurture, but so that they can watch the men do the dishes afterwards. The two women struggle to shop for and then prepare the elaborate dinner, though ultimately they do serve their roommates a good meal. In Season 4, the result is different: Deena and Sammi express their desires to be “real Italian ladies cooking dinner,” however, they lack the knowledge and skills necessary to complete this domestic task. Sammi cannot tell the difference between scallions and garlic while Deena can’t run an automatic dishwasher. In a previous season Snooki claimed that “a true Italian woman” is one who wants to “please everyone else at the table. And then when everyone’s done eating, you clean up and then you eat by yourself.” Yet, Deena and Sammi reject this paradigm when they decide to treat themselves to a meal prepared at a restaurant as their male roommates sit at home, hungry and waiting for their promised meal. The scene cuts back and forth between the women enjoying a nice lunch while the men debate whether or not they should just start cooking the meal themselves. When the women finally arrive home, they are distraught to see that the men are already well into meal preparations; their attempts at becoming “real Italian ladies cooking dinner” has failed.

Dick Hebdige writes that “…spectacular subcultures express forbidden contents (consciousness of class, consciousness of difference) in forbidden forms (transgressions of sartorial and behavioral codes, law breaking, etc.). They are profane articulations, and they are often and significantly defined as ‘unnatural.’” (92). Like the Mods, the guido subculture offers participants an opportunity to embrace their ethnic identities while simultaneously reconfiguring the traditional gender expectations embedded in those ethnic identities. The subculture allows men like Mike and Pauly D to feel masculine because they apply lipgloss, cook dinner, and obsess about their hair. And, although the Jersey Shore women embrace the stylistic requirements of their subculture, they reject the domestic and social roles placed upon them by their male castmates: they will not submit to unwanted sexual advances, cook, clean, or police their own bodies. Thus, Jersey Shore, for all its exploitative showcasing of substance abuse, sexual promiscuity, and ethnic slurs, offers a fluid view of gender roles within a community that is otherwise marked by a conservative view of gender.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution.” The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. Ed. Amelia Jones. New York: Routledge, 2003. 392-401.

Brooks, Caryn. “Italian Americans and the G Word: Embrace or Reject?” Time 12 Dec. 2009.

Cohn, Nik. “Tribal Rights of the New Saturday Night.” The New York Magazine. 17 June 1976.

Grossberg, Lawrence. “The Political Status of Youth and Youth Culture.” Adolescents and Their Music: If It’s Too Loud, You’re Too Old. Ed. Jonathon S. Epstein. New York: Garland Publishers, 1994. 25-46.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Metheun, 1979.

Sternbergh, Adam. “Inside the Disco Inferno.” The New York Magazine. 25 June 2008.

Thornton, Sarah. Club Cultures. Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 1995.

Tricarico, Donald. “Guido: Fashioning an Italian-American Youth Style.” Journal of Ethnic Studies 19.1 (1991): 41-66.

Tricarico, Donald. “Youth Culture, Ethnic Choice, and the Identity Politics of Guido.” Voices in Italian Americana 18.1 (2007): 34-86.

Warhol, Robyn R. Having a Good Cry: Effeminate Feelings and Pop-Culture Forms. Colmbus: Ohio State University Press, 2003.

Wilkinson, Tracy. “Italy’s Beautiful Obsession.” LA Times. 4 Aug. 2003.

Happy 2nd Birthday, Little Blog!

I do not have time to write a blog post today. In exactly one week I board a plane for Dublin (!) for a sure-to-be-fantastic conference, Gender Politics & Reality TV, hosted by University College Dublin. In addition to preparing for this five-day trip and writing my conference paper on gender roles on Jersey Shore, I must prepare for the start of the Fall semester at ECU, complete a panel proposal for the 2012 SCMS conference, AND finish a 7,000 word article that is due September 1st. What?

So, if I have all of this to do, why oh why am I writing a blog post right now? Well, my friends, it was 2 years ago today that I wrote my very first blog post. And since I missed my blog’s 1st birthday last year (I was busy!), I realized I could not ignore her again. Blogs have feelings too. So in honor of my blog’s 2nd birthday (she’s such a big girl now!) I look back at the last two years of my blog’s life and what I’ve learned.

*******

Social media was the gateway drug. When I first joined Twitter in March of 2009, posting my thoughts about the shows and films I was watching felt weird. Like I was shouting into the void. Over time, however, I gathered a few followers, started discussing popular culture with them, and realized that I really enjoyed these virtual conversations. So it was at that point that I decided I would start my own blog. The timing was perfect. I turned the final draft of my book manuscript in to my editor at the University of Texas Press in mid-August and I had several months of waiting to hear about the fate of my life’s work ahead of me. Why not blog the anxiety away? And blog I did.

My very first blog post, which served as my mission statement, promised this:

My hope is that you can read this blog with your morning coffee. I hope that what I have to say will enhance your experience of what you’re watching now or encourage you to go out and see something new.

More than anything though, I hope to have a conversation with those of you out there who love watching movies and television, who aren’t ashamed of the deep emotional connection you feel when sitting in front of the screen. What made you laugh out loud? What broke your heart? Am I too emotionally invested in the well-being of Nicolette Grant (Chloë Sevigny)?

I want my water cooler. Can you make that happen for me?

Sure, this smacks of Tom Cruise’s motivational “Come with me!” speech from Jerry Maguire (1996, Cameron Crowe). But let me let you in on a little secret: I loved Jerry Maguire.

And like poor Jerry, no one actually came with me for a while. Not even fishy-faced old Renee Zellweger. But over time, I did build a small, faithful readership. My readership is still relatively small, but that’s okay. You see, I’ve learned a lot from this blogging experiment:

1. Blogging makes you a better writer.

Blogging has had a liberating effect on my writing style. Before, when it was time for me to start writing an essay, I would read and read and read. Then I might sketch out an outline (which I would completely ignore once I started writing). Then I would try to start writing. I would stare at the screen and bite my nails. But blogging has taught me to start with the writing. It doesn’t matter what you write — just write. And after writing for a while I would start to see what it was that I wanted to write about — what my argument was — and this would then guide my research. After two years of blogging, I compose faster and better than I ever have in an entire lifetime of writing.

2. Blogging teaches you that your words are not gold.

This is related to my previous point. Before I started blogging I had a hard time editing myself. I felt that if I had taken the time to write a few paragraphs, then those paragraphs must be IMPORTANT. If I deleted those paragraphs, it meant that all the time I put into writing them was wasted. But blogging taught me that it’s OK to delete your writing. Sometimes I would compose 1,000 or more words of a blog post, only to realize that the post was going nowhere and I would delete it all. Just like that. I was able to delete these precious words without too much agony because I realized that the that time spent writing them wasn’t a “waste.” All that writing in the wrong direction cleared a path for me to write in the right direction. Yep, blogging taught me that.

3. Blogging makes you a better thinker.