Film

Performing Gender and Ethnicity on the JERSEY SHORE

This summer I had the good fortune of being accepted to the “Gender Politics and Reality TV” conference hosted by University College Dublin. I knew it would be difficult to attend this conference–it coincided with the first week of classes at the university where I work–and I knew it would be expensive. But I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to attend a small conference that was entirely focused on reality television. I am starting a new research project on MTV-produced reality shows and I thought this conference would help to kickstart my writing and research. So I planned well: I applied for and was awarded an international travel grant to help pay for the expensive trip, I enlisted two wonderful colleagues to teach my first week of classes for me, and I finished my paper and visual presentation a full week ahead of schedule. The night before I was set to fly to Dublin, I was finishing up my packing and it was only then that I thought to take a look at my passport. I had not flown out of the country since 2006 and I had no recollection of when the document was set to expire. It expired in 2008. Ooops.

I won’t describe the panic that followed this realization. I will just say that it took me about 2 hours of phone calls and internet research to conclusively determine that there was absolutely no way for me to get an updated passport in 24 hours (surprise!). I was going to have to cancel my trip to Dublin. I would like to offer a good explanation for why I purchased an international power adapter two weeks before my departure but only thought about my passport — the only way to legally leave my country — 24 hours before my departure. But I don’t have one. To a Type A personality like me, such an oversight is unthinkable. Like Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) in Memento (2000, Christopher Nolan), I have constructed a series of elaborate tricks to ensure that I remember to complete the many tasks required of a full-time working mother of two: alerts on my phone, copious notes in my planner, lists, lists and more lists. But this time, my system failed. Where was my Polaroid photograph? Where was the tattoo, written backwards across my chest, reading “GET PASSPORT RENEWED 4-6 WEEKS BEFORE DEPARTURE“?

There are many reasons why missing this trip was devastating to me: the expensive plane ticket, the embarrassment of contacting the conference organizer (a woman I greatly admire) and explaining what had happened, the loss of a much-needed vacation from my children (I love them, but sometimes Mama needs to get away), the chance to meet and talk shop with reality TV scholars in the context of a small, intimate conference, and the lost opportunity to present my work-in-progess to these experts and get their much-needed feedback. I can’t do much about the first four things, but I can, in fact, do something about the fifth. Although a friend attending the conference offered to read my paper for me and thus ensure that my mistake did not derail my panel (Thanks Jon!), I won’t be there for the conversation that follows. So I’ve decided to post my entire paper here on my blog (minus the clips, because I have yet to upgrade my blog so that I can upload my own clips). If you have an interest in subcultures, gender studies, or reality television, please read my paper below and offer me some feedback. While you do this I’ll be drinking a green beer and dreaming of Ireland…

Over the last few weeks an open letter to Randi Zuckerberg, the manager of marketing initiatives at Facebook, was circulated around various social media sites. The letter urges Zuckerbeg to “formally recognize the millions of people worldwide whose genders go beyond male or female by allowing other gender identities in Facebook’s profile fields.” The letter, which also serves as a petition, includes a series of testimonials from Facebook users who believe that the terms “male” and “female” do not accurately reflect their personal experience of gender, where gender is, to quote Robyn R. Warhol, “a process, a performance, an effect of cultural patterning that has always had some relationship to the subject’s ‘sex’ but never a predictable or fixed one” (4).

As I read through these testimonials, my mind drifted to MTV’s top-rated reality series, Jersey Shore, as I could imagine one its stars, Pauly D, submitting his own testimonial. If he did, it might go something like this:

“I am a heterosexual man who proudly spends 25 minutes styling my hair. I have earrings in both of my ears and have been known to wear lipgloss. I do not fit into Facebook’s limited gender categories.”

Okay, so Pauly D probably would not write a testimonial about his fluid understanding of gender, but he should. In this paper I argue that the guido identities celebrated in Jersey Shore reconfigure the way gender performs within the context of this Italian American subculture. When men like Pauly D adopt the styles, behaviors, and interests that U.S. culture has enforced as appropriate to women’s bodies, they, paradoxically, feel more like masculine men. In other words, Jersey Shore, for all its misogyny and ethnic stereotyping, actually highlights the performative nature of gender, and how it must be understood as a contingent and multiple process, rather than as a preexisting category (Warhol 5).

Before I go any further, I want to acknowledge that the term “guido” has a troubled history; some factions of the Italian American population see the term as offensive and view Jersey Shore’s cast members as minstrel-show caricatures (Brooks). Other Italian-Americans have reclaimed and reappropriated the moniker as a source of ethnic pride. Still other groups acknowledge that the term exists and therefore seek to understand and unpack its meanings.

My use of the term is neither an endorsement nor a rejection of any of these points-of-view. Instead, I deploy the term “guido” as a way to reference the ethnic subculture that is showcased, celebrated, and derided on Jersey Shore and in the process I hope that I do not cause any offense.

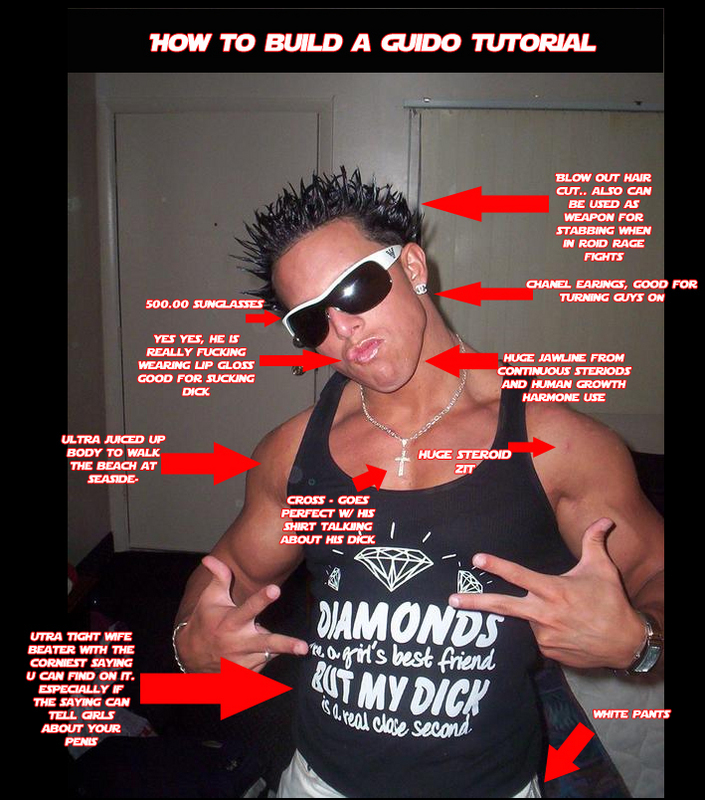

The term guido refers to a specific subcultural identity signified by a series of distinctive clothing styles, music preferences, behavioral patterns, and choices in language and peer groups. This label provides coherence and a solid ethnic character to a set of stylistic choices — including a preference for big muscles, gelled hair and tanned skin — selected by this particular youth subculture. Sociologist Donald Tricarico argues that the term guido denotes a way of being Italian that is linked to an ensemble of youth culture signifiers. He writes: “To this extent, ethnicity also draws boundaries intended to include some and exclude others. It establishes parameters for stylized performances in the competition for scarce youth culture rewards” (“Youth Culture” 38). In addition to the usual rewards of peer acceptance and recognition as a member of the subculture, embracing the signifiers of the guido subculture provides the Jersey Shore’s cast members with fame, money, and lucrative business opportunities. And because MTV provides such powerful incentives for Jersey Shore cast members to perform their ethnicity on national television, MTV’s cameras artificially inflate the signifiers of the subculture. Thus, Jersey Shore becomes a unique opportunity to analyze the performative nature of gender within the framework of an ethnic subculture. In this context “performative” does not just refer to gender as a performance; I am also using the term as a way of understanding, to quote Warhol again, “the body not as the location where gender and affect are expressed, but rather as the medium through which they come into being” (10). In Jersey Shore, gender performs in a unique way in that behaviors typically coded as effeminate actually constitute—rather than negate—masculinity.

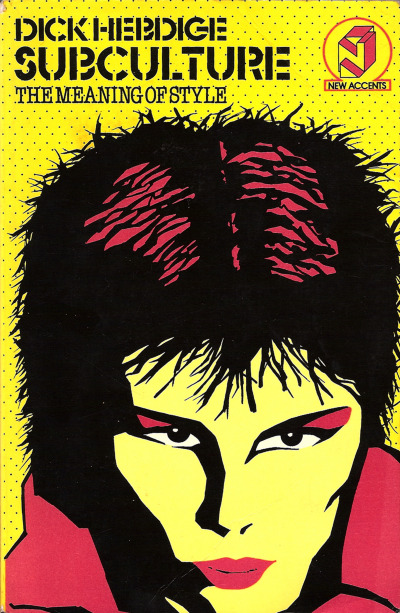

According to Dick Hebdige, every youth subculture represents “a different handling of the ‘raw material of social existence’” (80). While subcultures represent countercurrents within the larger hegemonic structures of society, they are nevertheless “magical solutions” to lived contradictions. In other words, although subcultures initially pose a “symbolic challenge to a symbolic order,” these subcultures are inevitably, almost instantaneously, recuperated into the very system they are supposedly challenging (Grossberg 29). According to Tricarico, the guido “neither embraces traditional Italian culture nor repudiates ethnicity in identifying with American culture. Rather it reconciles ethnic Italian ancestry with popular American culture by elaborating a youth style that is an interplay of ethnicity and youth cultural meanings” (“Guido” 42). Because Italian Americans have the ability to pass for a range of ethnic identities in America, including Jewish, Latino, or Greek, self-identified guidos use the signifiers of their subculture as a way to make their ethnic identity visible and unambiguous to those outside of the subculture. Thus, guidos are different from many other ethnic subcultures in that style is used to highlight and emphasize ethnic differences, rather than to escape from their presumed constraints (Thornton).

The guido subculture in its current form can be traced back to various Italian American street gangs from the 1950s and 1960s, such as the Golden Guineas, Fordham Baldies, Pigtown Boys, Italian Sand Street Angels, and the Corona Dukes, among others, who hailed from the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn (Tricarico “Youth Culture” 49). Many of these gangs were under the tutelage of the local Mafia, who organized youth into crews and put them to work. However, much like the 1970s African American, urban, youth gangs that sublimated some of the more violent aspects of their subculture into prosocial avenues such as rapping, break dancing, and graffiti art, over time the violent activities of Italian American youth gangs were translated into purely stylistic concerns (Tricarico “Guido” 48).

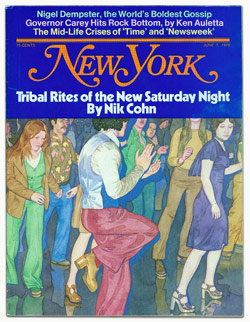

Then, in 1976, British rock journalist Nick Cohn published “Tribal Rights of the New Saturday Night” in New York Magazine. The article follows a young Italian American named Vincent who spends his days working a “9 to 5 job” in a hardware store and his Saturday nights in the disco clubs of New York City. Cohn describes the regimented life of Vincent and his peers in the following way: “graduates, looks for a job, saves and plans. Endures. And once a week, on Saturday night, its one great moment of release, it explodes.”

The article, which was the inspiration for the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, serves as the origin myth for the modern guido subculture. The article and film showcased how working class Italian American youths escaped the tedium of their cramped apartments and restricted finances by participating in the glamorous, fantasy world of Manhatttan’s disco clubs.What is most fascinating about this elaborate origin myth is that 20 years later Nik Cohn admitted that, facing pressure to come up with a story about American discos–he made his story up. He based Vincent not on any actual Italian American but on a Mod he knew back in England (Sternbergh).

Indeed, like the Mods of 1960s England, American guidos generally hail from the working classes, and are preoccupied with fashion, music, dancing, and consumerism. Within the Mod subculture, it was acceptable, even mandatory, for men to be fastidious and vain about their clothing — usually expensive, well-tailored suits — and hair (Hebdige 54). In fact, these stereotypically “feminine” interests became “masculine” within the context of the Mod subculture. Similarly, the signifiers of the male guido—gelled hair, earrings, decorative, form-fitting T-shirts and jeans, and even lip gloss—are gendered as masculine, not feminine, within the confines of their subculture.

Pauly D’s elaborate hair regiment and Mike Sorrentino’s obsession with his abdominal muscles also accord with the Italian concept of “bella figura,” which refers to the practice of “peacocking” or “presenting the best possible appearance at all times and at any cost” (Wilkinson). Bella figura, a concept dating back to the 1400s, means making the best possible presentation of one’s self at all times in order to conceal whatever the individual may otherwise be lacking in looks, money, education, or experience. We can read the contemporary guido’s obsessions with grooming as the fulfillment of bella figura, and thus, as an inherently Italian practice. To spend 25 minutes on your hair is not feminine in Pauly D’s world; rather, it is a signifier of his Italian masculinity. The guido identity therefore allows Italian American males to engage in activities which would normally be coded as feminine, and therefore, off-limits.

Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino is a striking example of the bella figura legacy in the guido subculture. Several Jersey Shore episodes feature scenes in which the roommates must wait for Mike to complete his grooming before they can head out to the club. The editing of these scenes suggests that Mike spends far more time on his appearance than either his male or female roommates do. Mike has also built a reputation for codifying his daily toilette with formal titles, like “Gym, Tan, Laundry.” In addition to his GTL, Mike makes weekly trips to the barbershop for haircuts and eyebrow waxing, all in service of becoming “FTD” or “fresh to death.” The following Access Hollywood clip demonstrates the performative nature of gender within and outside of the guido subculture.

Click here to watch

For the viewing audience that is not a part of the guido subculture, this segment is played for laughs: the joke is that these two muscular, heterosexual men are enjoying “feminine” pleasures like facials and hand massages. These gender acts make them appear effeminate to those outside of their subculture. However, for Mike, Pauly D, and other members of their subculture, grooming is what makes them masculine. Judith Butler explains this more elegantly: “As performance which is performative, gender is an ‘act,’ broadly construed, which constructs the social fiction of its own psychological interiority” (399).

Vinny provides another useful example of gender performativity in Jersey Shore. In the series premiere, Vinny, who calls himself a “mama’s boy” and a “generational Italian,” immediately distances himself from the stylistic trappings of the guido subculture, explaining “The guys with the blow outs, the fake tans, that wear lip gloss and make up…those aren’t guidos, those are f**king retards!” Although he claims to prefer stereotypically masculine activities like playing pool and basketball over “GTL,” throughout Season 1 Vinny is coded as the least masculine male cast member in the house. While other male cast members regularly become embroiled in fistfights and bring home a new sexual conquest every night, Vinny distances himself from these stereotypically aggressive male behaviors. He is the resident “nice guy.”

This sensitive persona shifts markedly in Season 3, however, when Vinny is pressured by his male housemates to get both of his ears pierced with a pair of diamond studs. In the context of American culture, getting both ears pierced, especially with diamonds, is a style choice associated with women and femininity. However, the Jersey Shore cast equates this gender act with masculinity and treats the event itself as a male rite of passage. For example, when Vinny agrees to get his ears pierced, Pauly D exclaims “My boy’s becoming a man!” Later, in his confessional interview, Vinny explains that he endured the pain of the ear-piercing “like a G.” Thus, not only is double ear-piercing considered masculine within the guido subculture–withstanding the pain of this important ritual is equated with being a violent, cocksure gangster, the ultimate signifier of American masculinity. Once the piercing is complete, Pauly and Ronnie delight in the results like two proud parents. They even ask Vinny if he “feels different,” much as mothers ask their daughters if they “feel different” after getting their first menstrual period.

Vinny does not pierce his ears because he is a man; he becomes a man through the act of piecing his ears. In other words gender acts that are coded as feminine outside of the guido subculture actualize and activate Vinny’s sense of himself as a man within the subculture. The contradiction between the nature of these behaviors and the gender they perform highlights the contingent nature of gender itself. So how does Vinny act now that he has finally “become a man”? In addition to, in his own words, “walking with a gangster limp” and wearing his baseball cap at a “gangster lean,” his newly-pierced ears compel Vinny to go after women like a dog in heat. At the club that evening, the normally polite, somewhat shy reality TV star dismisses the women who approach him for not being attractive enough. Later, after his attempt at coitus with a woman from the club fails, Vinnie turns to Snooki, his roommate and occasional lover, for a quick tryst. When Snooki dismisses Vinny’s advances as offensive, the newly masculinized Vinny picks up his small conquest and attempts to drag her into his bedroom. Vinnie’s roommates marvel at his uncharacteristically aggressive behavior and tellingly attribute it to his new earrings. Here, subcultural style “empowers” Vinnie to indulge in the stereotypes of masculine behavior that he has previously avoided.

Earlier I mentioned that the male guido’s, obsession with grooming and style has come to stand in for the violence that this immigrant group once needed to deploy in order to survive. The male guido’s attention to his toilette, an affectation generally associated with effeminacy, stands in for the stereotypically masculine behaviors of fighting, killing, and defending one’s home turf that have been rendered superfluous in contemporary society. Thus, if being physically strong was once a prerequisite for membership in a street gang in order to defend oneself from outsider attacks, a muscular physique is now an end in itself; it is what makes Mike “feel like a real man.” But what creates femininity within this subculture? The answer to this question is more complicated. Certainly, the female guido style is codified: the women must wear their hair long (with the aid of highly flammable hair extensions), and usually dye it dark, in accord with their Italian heritage. Make up must be bright and noticeable, with an emphasis on the eyes, lips, and nails (Tricarico “Guido” 44).

And while it is clear that Snooki, J Woww, Deena and Sammi spend a lot of time on their appearances (after all, Snooki’s pouff doesn’t do itself), far more screen time is devoted to the women’s defiance of femininity. In almost every episode female cast members belch loudly, urinate outside, or vomit on camera, behaviors that are often associated with masculinity or at least with the un-feminine. Deena often falls due to extreme intoxication and on several occasions Snooki has inadvertently exposed her genitals to MTV’s cameras. In other words, the women of the Jersey Shore house are lusty, hungry, messy, and quite comfortable with their own bodily functions.

Perhaps the strongest rejection of traditional female gender roles occurs in the handling of the all-important Sunday night meal. Several Jersey Shore episodes feature a scene in which the roommates sit down to an elaborate Sunday night dinner. In most Italian homes, the matriarch does the shopping, cooking, and cleaning for this traditional, multi-course meal. When, for example, Vinny’s mother visits the house in season one, Pauly D compares her to his own mother, whom he describes as an “old school Italian,” because she cleans the Jersey Shore house after fixing the roommates an extravagant lunch. Despite these defined roles, passed on from one generation of Italian American women to the next, the women of Jersey Shore either ignore or reject these gender expectations. Several scenes in the series are devoted to the women’s refusal to shop, cook or even clean up after house meals. In season 2, Jenni and Snooki agree to cook the Sunday dinner, not out of a sense of responsibility or a desire to nurture, but so that they can watch the men do the dishes afterwards. The two women struggle to shop for and then prepare the elaborate dinner, though ultimately they do serve their roommates a good meal. In Season 4, the result is different: Deena and Sammi express their desires to be “real Italian ladies cooking dinner,” however, they lack the knowledge and skills necessary to complete this domestic task. Sammi cannot tell the difference between scallions and garlic while Deena can’t run an automatic dishwasher. In a previous season Snooki claimed that “a true Italian woman” is one who wants to “please everyone else at the table. And then when everyone’s done eating, you clean up and then you eat by yourself.” Yet, Deena and Sammi reject this paradigm when they decide to treat themselves to a meal prepared at a restaurant as their male roommates sit at home, hungry and waiting for their promised meal. The scene cuts back and forth between the women enjoying a nice lunch while the men debate whether or not they should just start cooking the meal themselves. When the women finally arrive home, they are distraught to see that the men are already well into meal preparations; their attempts at becoming “real Italian ladies cooking dinner” has failed.

Dick Hebdige writes that “…spectacular subcultures express forbidden contents (consciousness of class, consciousness of difference) in forbidden forms (transgressions of sartorial and behavioral codes, law breaking, etc.). They are profane articulations, and they are often and significantly defined as ‘unnatural.’” (92). Like the Mods, the guido subculture offers participants an opportunity to embrace their ethnic identities while simultaneously reconfiguring the traditional gender expectations embedded in those ethnic identities. The subculture allows men like Mike and Pauly D to feel masculine because they apply lipgloss, cook dinner, and obsess about their hair. And, although the Jersey Shore women embrace the stylistic requirements of their subculture, they reject the domestic and social roles placed upon them by their male castmates: they will not submit to unwanted sexual advances, cook, clean, or police their own bodies. Thus, Jersey Shore, for all its exploitative showcasing of substance abuse, sexual promiscuity, and ethnic slurs, offers a fluid view of gender roles within a community that is otherwise marked by a conservative view of gender.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution.” The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. Ed. Amelia Jones. New York: Routledge, 2003. 392-401.

Brooks, Caryn. “Italian Americans and the G Word: Embrace or Reject?” Time 12 Dec. 2009.

Cohn, Nik. “Tribal Rights of the New Saturday Night.” The New York Magazine. 17 June 1976.

Grossberg, Lawrence. “The Political Status of Youth and Youth Culture.” Adolescents and Their Music: If It’s Too Loud, You’re Too Old. Ed. Jonathon S. Epstein. New York: Garland Publishers, 1994. 25-46.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Metheun, 1979.

Sternbergh, Adam. “Inside the Disco Inferno.” The New York Magazine. 25 June 2008.

Thornton, Sarah. Club Cultures. Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 1995.

Tricarico, Donald. “Guido: Fashioning an Italian-American Youth Style.” Journal of Ethnic Studies 19.1 (1991): 41-66.

Tricarico, Donald. “Youth Culture, Ethnic Choice, and the Identity Politics of Guido.” Voices in Italian Americana 18.1 (2007): 34-86.

Warhol, Robyn R. Having a Good Cry: Effeminate Feelings and Pop-Culture Forms. Colmbus: Ohio State University Press, 2003.

Wilkinson, Tracy. “Italy’s Beautiful Obsession.” LA Times. 4 Aug. 2003.

Revisiting THE MAGIC GARDEN, or How I Plan to Keep my Girl Off the Pole

One of the great joys of parenting young children is the chance to return to activities that you enjoyed as a child. Having a child gives you license to play with toys, watch children’s television shows, go to Disney World, and to eat unhealthy shit like Nutty Sundae Cones and Chee-tos because “It’s a treat for the kids.”

However, one thing that I have noticed is that certain cherished icons from my youth have changed a lot over the last few decades. For example, as a child in the 1980s I adored my set of My Little Ponies. They were anthropomorphic for sure — but still fundamentally “horsey.” They were pretty but also demure. Clearly, these were ponies who were not yet interested in boys or parties.

When my daughter was around 2 years old, she received her first My Little Pony. As we opened the package, I was horrified. This little pony is clearly hot to trot:

So what’s different? First, the pony is skinnier. That’s right. Skinnier. Because little girls aren’t exposed to enough images of impossibly skinny women. Today even plastic ponies are paranoid about the size of their asses. Now take a look at that snout. This new breed of pony has had a nose job. Nose jobs for ponies? Rainbow Dash will probably tell you that she had a “deviated septum,” but we know the truth. Other changes: longer, more tapered legs (Pilates?), longer manes and tails (hair extensions?), and more body art (kids today love their tattoos).

Bu Hasbro isn’t the only company invested in defiling my innocent childhood memories. Let’s take a look at a Strawberry Shortcake doll, circa 1980:

I have many fond memories of playing with this Strawberry Shortcake doll and her beloved cat, Custard (they both smell like strawberries!) in my childhood bedroom. I especially loved Strawberry’s big, floppy hat, which implied that she spent her days baking delicious strawberry confections for her pals Lemon Meringue and Blueberry Muffin. There is nothing “sassy” or “fierce” about this doll. In fact, she’s sort of a dork. Just like I was at age 6 and just like all 6 year olds should be. I am very wary of “hip” children.

Now take a look at the Strawberry Shortcake doll my daughter plays with:

As with My Little Ponies, today’s Strawberry Shortcake appears to have grown up prematurely. The doll I played with as a child was a child: fat cheeks, stubby legs, lame clothes, etc. My daughter’s doll looks more like a precocious pre-teen: she’s lost her gigantic hat, she’s wearing heavy make-up, and she is dressed in the requisite preteen outfit of miniskirt n’ leggins. Oh how today’s teens love the leggins.

And here’s a nice comparison of the 1980s Strawberry Shortcake cartoon heroine and her contemporary manifestation on TV:

In her wonderful book, Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Girlie-Girl Culture, Peggy Orenstein analyzes contemporary girl culture, focusing several chapters on the premature sexualization of girls. In particular, Orenstein cites the concept of KGOY or “Kids Getting Older Younger.” KGOY is the idea that “toys and trends start with older children, but younger ones, trying to be like their older brothers and sisters, quickly adopt them. That immediately taints them for the original audience. And so the cycle goes” (84). This might explain why my daughter’s Strawberry Shortcake doll is so much sluttier than mine ever was! Orenstein laments the early sexualization of girls, who develop an appetite for make up, short “sassy” skirts, and rhinestones at an early age. For another eye-opening take on this issue, read Lisa Bloom’s short piece in The Huffington Post, “How to Talk to Little Girls.”

But why is this problematic? I mean, can’t my daughter wear some lip gloss and strut around in the clear plastic princess heels a well-meaning friend bought for her? Isn’t she just exploring a role and enjoying the fantasy? In an interview with NPR’s Diane Rehm, Orenstein explains:

“We have confused desirability with desire, so that girls feel they’re supposed to be desirable. But they don’t really understand their own desire. And when I talked about that with a researcher who studies girls and desire, she said that by the time girls are teenagers, when she asks them how they felt about an intimate experience, they respond by telling her how they felt they looked. And she has to tell them that looking good is not a feeling.”

When I read these words, I actually get tears in my eyes (as should you). Why is this happening to our daughters? How can we stop it? Often it feels like a losing battle. I may not buy my daughter slutty-looking dolls or T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Pampered Princess,” but other people do. And what should I do with those dolls and T-shirts? Throw them away? Explain to my 5-year-old that Strawberry Shortcake shouldn’t be wearing make up yet? That instead Strawberry Shortcake should look inside for her true worth?

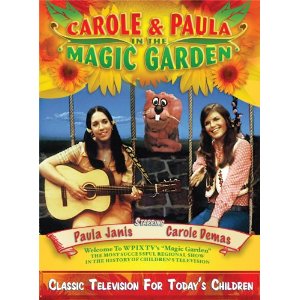

One way to counter this early sexualization in popular culture is to never let my daughter watch TV or go to Target or have a birthday party or leave the house. But that’s not very realistic. So another option is to direct her towards popular culture that has nothing to do with princesses or prettiness or lip gloss or sparkles, but that still appeals to a child’s sense of wonder and fantasy. And that is just what I did for my daughter’s 5th birthday [pats self on back]. I purchased a DVD of the classic children’s television series, The Magic Garden.

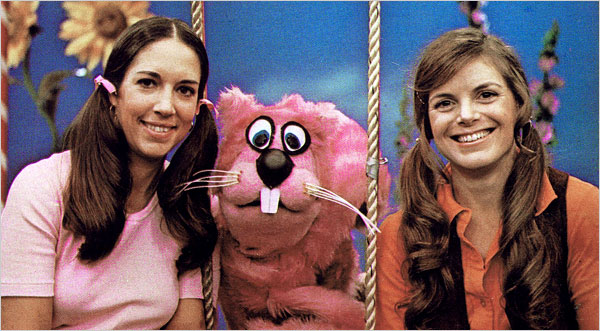

For those who were not young children in the early 1980s or did not have cable, The Magic Garden was a children’s television show produced for New York City’s WPIX station, aka, channel 11. The show aired from 1972 until 1984, and, as the cover of the DVD proclaims, it remains “the most successful regional show in the history of children’s television.” The Magic Garden centers on two women, Carole Dumas and Paula Janis, who reside in a “magical garden of make-believe.” During the course of a typical 30-minute episode, Carole and Paula will sing several songs (in beautiful harmony), perform a classic fable with the help of the Story Box, read a joke or riddle from the giggling garden of plastic flowers known as the Chuckle Patch, and teach a lesson to the show’s antagonist, Sherlock the Squirrel. There was not a lot of children’s television when I was a kid, so every show was precious to me. I have distinct memories of running into the den on weekday afternoons, panicky that I might miss some of The Magic Garden‘s glorious opening theme song (a panic my children will never know due to the DVR):

I’m not exaggerating when I say that I still feel shivers of excitement when I see this clip; I am immediately sent back to my childhood. I remember my joy at seeing the window open onto the cheesy, 1970s-era studio set (it even looked cheesy to me as a child), as the camera slowly tracks forward until it reaches the show’s harmonizing stars, Carole and Paula, sitting on swings and looking swell. As I child, I loved their fabulous hippie hair, always styled the same way: parted down the middle and tied into two long ponytails. And I loved how inviting these women were: they smiled and cajoled, but not in the syrupy sweet way that other children’s show hosts of the era did, like Mr. Rogers or Romper Room‘s Miss Molly. It didn’t feel like they were adults talking down to me. Instead they felt like the coolest babysitters ever who wanted me to come and play in the magic garden with them!

When my daughter opened up The Magic Garden DVD set on the morning of her 5th birthday, her face fell. “What is this?” she whined. “It’s The Magic Garden!” I exclaimed. “It was Mommy’s favorite TV show when she was 5!” My daughter glanced at the cover one more time and then dropped it on the table to see what else we had bought for her. I did not let on that I was crushed.

Later in the week when my daughter was about to sit down for her much-anticipated, daily 30-minute dose of “screen time,” I asked her “So do you want to watch the new DVD Mommy bought for you?” My daughter scowled, “I didn’t even ask for that!” It was not until I had to drive my two children from Greenville, NC to Charleston, SC by myself that I offered up the DVDs again. My 18-month-old son hates the car. He hates being strapped in to anything and he hates looking at the back of my head (all attention should be on him at all times, a reasonable demand). When I could not stomach his screaming any longer I decided to put The Magic Garden into my minivan’s built-in DVD player (God bless the Mensch who invented that technology). As soon as the opening strains of the theme began to play, my son stopped crying. He was mesmerized. And so was my daughter. On our return trip to Greenville, my daughter only wanted to watch The Magic Garden: not Cinderella, not The Little Mermaid, not even that perennial car trip favorite, Dora Saves the Crystal Kingdom.

Currently, my children are completely enamored with The Magic Garden. This surprises me because 1) my son has never really sat still long enough to watch a TV show and 2) compared to the slick production values and high-definition images of contemporary live-action children’s shows like The Fresh Beat Band or even Yo Gabba Gabba! (which even seems to strive for a low-budget aesthetic), The Magic Garden is positively low-rent. The image transfer is grainy and blurry and the set, with it’s astroturf and plastic flowers looks like a parody of a bad public access television show. But that is what’s so wonderful about this show.

In the above Story Box segment (a feature of every episode), Carole and Paula dig through a beat up old trunk and pull out costumes made out of construction paper. Clealrly these items were put together minutes before the cameras rolled. For the story of the “Fox and the Crane,” for example, Carole’s Fox costume consists of a set of little brown ears attached to a plastic headband and the Crane is signified by a bright yellow construction paper cone that Paula holds up to her mouth. So in order to follow the story, children had to … use their imaginations!

And let’s talk about Paula’s and Carole’s wardrobes for a minute. As I recall, the women never wore dresses or skirts. Instead they always wore pants or jeans (or what my Nana used to call “dungarees”). These women didn’t look like magical fairy princesses or even cool teenagers. They looked like my summer camp counselors or my babysitters — fun women who played “steal the bacon” with me or hid under my bed during a game of hide and seek.

And how about the two puppets who regularly appeared on the show, Sherlock the Squirrel and Flapper the Bird? The prop department couldn’t even spring for glass eyes — both characters instead have either felt eyes or paper eyes with the pupils drawn in. This aesthetic has the curious effect of making it appear as if Sherlock and Flapper are stoned or at least very bored — even when their voices are animated.

But this is the charm of The Magic Garden. No CGI, no sparkles, no high heels or make up, no faux “girl power!” Instead, it’s two real women, singing in their real voices, beckoning children, to “come and see our garden grow.” The only complaint I have about this DVD set is that it only contains 10 episodes (as well as a bonus 6-song CD). When my daughter told me that she wanted to watch this show “forever,” I had to break the news to her and she was devastated. “What? That’s all there is?” There were, in fact, 52 episodes of The Magic Garden that aired between 1972 and 1984, but my guess is that the 10 that appeared on the DVD were all that WPIX had saved. After, how could they foresee the phenomenon of TV-on-DVD?

I don’t want it to seem like I am implying that by buying my daughter a collection of TV episodes from my youth that I am somehow keeping her from becoming sexualized at an early age. The Magic Garden alone will not keep my girl “off the pole” (to quote a great Chris Rock bit). Orenstein concludes her (often frightening) book in this way:

“… our role is not to keep the world at bay but to prepare our daughters so they can thrive within it. That involves staying close but not crowding them, standing firm in one’s values while remaining flexible … The good news is, the choices we make for our toddlers can influence how they navigate [culture] as teens. I’m not saying we can, or will, do everything ‘right,’ only that there is power — magic — in awareness” (192).

Preach on, Peggy.

Indeed, all I can do is make my daughter aware of what the world is like, and what traps might lie ahead as she makes her way as a young woman. I will tell her that once a woman starts wearing make up she will find that she doesn’t like her face any other way. I will tell her that while I think she is beautiful, she should never be defined by the way she looks. I will tell her that envy is a sickness and that she should therefore never compare her appearance to another woman’s. I will tell her that her body is first and foremost something that she should enjoy. I will tell her that she must love that body, because it is the only body she will ever have. And, while I wait for the day when she slams her bedroom door in my face, rejecting all of that advice, I can offer her a “magical garden of make believe, where flowers chuckle and birds play tricks and a magic tree grows lollipop sticks.” I like hanging out there too, preferably while eating a Nutty Sundae Cone.

Making Peace with my Zombies: A Personal Narrative

My husband and I have really been enjoying HBO’s new fantasy series, Game of Thrones. In fact, it’s the perfect show in that it bridges two of our most divergent TV tastes; he loves costume dramas and anything set in a castle (which I normally hate) while I love a show with an impending sense of doom (“Winter is coming!”). But one thing threatens to destroy our shared television bliss: zombies. Of course, none of the many enticingly-edited previews leading up to the April 17th Game of Thrones premiere led me to believe that the series would include zombies. No, that little surprise happened in episode three, “Lord Snow,” when young Bran (Isaac Hempstead-Wright), bedridden after being pushed out of a tower for seeing something very, very naughty (it rhymes with bincest), asks his nurse to tell him a scary story. Old Nan complies and tells Bran, a “summer child,” all about an endless winter that happened thousands of years ago. During this winter the sun disappeared all together and mothers smothered their babies rather than see them starve. And, during this winter, the “white walkers” came. These white walkers ate babies! Babies , for crying out loud! Upon hearing this story I was all “Hell to the no!” because I had really fallen in love with Game of Thrones and I did not want to give it up just because it had a few zombies in it. You see, I have an intense zombie phobia. And like all phobias, this one is threatening to take away something I love. So I’ve decided to use this blog post to revisit my zombie phobia and to try to understand it’s hold over me. I hope you don’t mind the indulgence.

This story begins with my older brother, Adam, and his obsession with horror films. The early 1980s was a golden age for the horror film. There were numerous teen slasher film franchises, including Nightmare on Elm Street (1984, Wes Craven), Halloween (1978, John Carpenter), and Friday the 13th (1980, Sean S. Cunningham). But my brother was into a very specific kind of horror film: the splatter film. In conventional horror films, like Dracula (1931, Tod Browning) or Frankenstein (1931, James Whale), the monster is foreign and threatens the characters’ way of life. Yes, there is the threat of bodily harm, but these films (due to the restrictions of the Production Code), rarely dwelled on the destruction of the human body. Victims screamed and then drifted out of the frame. Nice and clean.

But the horror of the splatter film comes from its focus on the systemic destruction of the human body. This horror cycle is preoccupied with the faithful recreation of blood, organs, skin, and bone so that it may later rip these replicas of the human form to shreds.

The splatter film takes what is usually on the inside of the body — safely contained within our skin — and reveals it to the outside. What is especially important about the splatter film is not the high body counts (leave those to Rambo), but the obsessive focus on death itself. Victims are rarely shot with bullets or forced to ingest poison. Instead, the destruction of the human body must take place at close range with weapons — clubs, machetes, knives, fingernails, teeth (shudder) — that require the killer and the victim to have intimate contact with one another. The messier, more prolonged, and more painful the death is, the better.

Yes, these were the kinds of horror films that my brother always seemed to be watching in the mid-1980s. And, naturally, as a younger sister, I wanted to be doing everything my older brother was doing. If he was going to watch Day of the Dead (1985, George Romero), then damn it, I was going to watch it too. I asked my brother about the fateful day that changed everything for me — the day we watched Night of the Living Dead (1968, George Romero) on VHS in our family den. He thinks it was somewhere around 1986, which means I would have been 10-years-old and he would would have been around 15-years-old. And while I distinctly remember him coaxing me to watch the movie by telling me that it really wasn’t that scary, my brother remembers it differently: “I don’t recall forcing you to watch it, you were into it like any kid looking for a thrill would be.” Doesn’t that sound exactly like something a drug dealer would say? Regardless of how it happened, there I sat, for 96 minutes, and watched as a series of reanimated corpses cornered and ate a houseful of people. Including a little girl, just like me. WTF, George Romero?

Looking back on this phase of my pop culture upbringing, I do wonder where the hell my mother was. The film professor in me appreciates that she didn’t do much censoring of television or movies — my brother and I pretty much watched what we wanted to watch. My Mom only started to get concerned about my brother’s horror movie fascination when Fangoria magazine began to arrive in our mailbox every month. Those covers freaked me out.

But by that time, it was too late for me. The deep damage to my psyche was already done. And the real problem? I liked zombie movies. They scared me more than any other horror film and I really liked being scared. Zombie movies combined all of my greatest fears: dead bodies (I still have never seen a dead body), being chased by an unrelenting enemy, painful, prolonged death, and the possibility of being turned into a monster. So I continued to watch zombie movies with my brother. And like any older brother worth his salt, Adam pinpointed my fear and discovered clever ways to exploit it. For example, after we watched Dawn of the Dead (1978, George Romero) together, my brother came up with a great tormenting device: he would chase me around the house pretending to be a zombie. He’d put his arms out in front of him, cock his head to the side, and hum the Muzak that was playing in the mall for most of Dawn of the Dead (see YouTube clip below). This horrible chase would always end the same way — with me locking myself into the nearest available bathroom and waiting, panting and terrifed, for my brother to get bored and lumber away (just like in a real zombie movie). To this day, when I hear generic-sounding Muzak, the muscles in my stomach tighten up.

Due to the combination of watching zombie movies at an age when I was too young to process their terrifying images and being chased around the house by my faux-zombie brother over and over again, I was plagued, for decades, with zombie-themed nightmares. In these dreams I was plunged, in medias res, into the climax of an epic zombies versus humans battle. The battle would conclude in one of two ways: either I was holed up in an old house with a group of survivors — sometimes I knew them, sometimes I didn’t — and we would bide our time, waiting for the moment when the zombies would finally burst through our hastily constructed barricade. Or (and this was the worst scenario), I was by myself, being chased by a horde of hungry zombies who were always just inches behind me. At some point during this recurring nightmare I would recognize that I was dreaming and I would have to make a decision: continue to flee the zombies (and thus, prolong the feeling of absolute terror) or allow the zombies to attack me (which would allow me to finally wake up). Neither option is really an option, you dig?

The turning point for me and my love/hate relationship with zombies happened in 2002, when I went to see 28 Days Later (Danny Boyle) with my friend, Coral. After the movie, Coral was going to drop me off at my empty house; my boyfriend (now my husband) was out of town. But I knew that sleeping alone in my empty house was going to be an impossibility. So instead I ran inside, grabbed my toothbrush and my dog, and hopped back into Coral’s car. As I lay there that night on Coral’s futon, painfully aware of the inanity of a grown woman having to sleep over at a friend’s house after watching a scary movie, I came to a decision: no more zombie movies. And I’ve kept to that, mostly. I lapsed in 2004, when I rented the remake of Dawn of the Dead (Zack Snyder) (which, by the way, was great). I did this when my husband was out of town and I paid for it with a night of insomnia. I haven’t watched a zombie movie since. And now I only have a few zombie-themed nightmares each year. I still get sad though, like when a group of my friends all went to see Zombieland (2009, Rubin Fleischer) and I had to say “Sorry, friends, just can’t do it!” And I know that AMC’s The Walking Dead is supposed to be great, but I’ll never know its pleasures. Instead, I try to view my zombie phobia the way a lactose-intolerant person views ice cream: you can have a sundae, but your ass is going to pay for it later.

Which brings me to the present day and Game of Thrones. Except for a brief glimpse of a blue-eyed little girl with a bloodied mouth (who I am assuming is a white walker?), no zombies have appeared in the series. But, as Ned Stark (Sean Bean) keeps warning us, “winter is coming” and with it, zombies. When they arrive, I might have to abandon this great television series, or risk giving up my dreams to the undead once again.

So, am I alone in my zombie phobia? Is anyone else out there zombie-intolerant? Or is there another movie monster that plagues your nightmares? I’d love to hear your thoughts below.

BRIDESMAIDS, Will You Be My BFF?

A few months ago I made some New Year’s resolutions. Not the kind in which I vow to be a better person or promise to call my mother more (sorry Mom). Instead, I made some popular culture New Year’s resolutions. Number 2 on my list was a promise to see more films while they are still in the theaters. I do eventually get around to seeing all of the movies that I’m interested in, once they are released on DVD. But certain films are just better when viewed in the theater: special effects-laden science fiction and action films, horror films, and comedies. The big screen and surround sound provided by the movie theater offer the ideal setting for the visual and auditory spectacle that is the raison d’être of science fiction and action films. The second two genres — horror and comedy — are all about the affect they produce in the viewer: horror films aim to horrify you and comedies aim to make you laugh. When you see these kinds of films in the theater, with an audience of excited moviegoers who are very much interested in being horrified or being amused, just like you, then the viewing experience is greatly enhanced. I scream a little bit louder and laugh a little bit harder when I share the movie experience with a group of strangers.

Although I had no one to accompany me to the Greenville Grande on Saturday night (for those keeping track, that is the Greenville movie theater that does not smell like pee), I decided that I really did need to go and see Bridesmaids. I’ll be out of town this weekend and given Greenville’s track record with films that don’t contain talking animals or exploding spaceships, I was worried that Bridesmaids might be gone before I had a chance to see it (it is a “chick flick,” after all). It was important for me to see this comedy in the theater, so I went alone. Before you start feeling bad for me, going to see a movie on a Saturday night all by myself, let me assure you: I had a great time. I am not yet in crazy cat lady territory — at least not until after the kids go to college.

When I walked into the theater, I saw that it was packed. This is key for a comedy. The more people who are in the room, the better. Also, I quickly discovered that the gentleman sitting behind me was an unapologetic movie talker. I used to really hate movie talkers. I would sit in my seat and fume away, wondering why this jerk was out to ruin my viewing experience. But now that I have two young children, going out ot the movies is a rare treat (hence the New Year’s resolution), and so I have come to appreciate all the fine nuances of the movie-going experience. And this young man was a real pro. He didn’t modulate his voice at all — his comments were as loud and clear as if he were sitting at home, watching the movie on DVD. And his commentary was completely banal. During the scene in which Annie’s (Kristen Wiig) nutty roommate, Brynn (Rebel Wilson), begins pouring frozen peas over her sore tattoo (as opposed to placing the entire bag on the swollen area), he declared “That chick’s so dumb, man!” Later, when Annie’s crappy little car finally breaks down, he informed the theater, “That car’s a beater!” Yes, Movie Talker, that car sure was a beater. Thanks for the head’s up!

With a comedy I think it’s important to set the tone early, so the audience knows what to expect. So it was fitting that Bridesmaids opened with Annie and her rich, emotionally unavailable “fucky buddy,” Ted (Jon Hamm), having very active, very unsexy, sex. I think it’s a testament to both Kristen Wiig’s and Jon Hamm’s comedic abilities that they were able to take something so inherently sexy — naked Jon Hamm having sex — and make it cringe-worthy and awful. The next morning Annie asks Ted if he wants to start dating. He shoots her down (and the tone of the conversation implies that the subject has come up before) and tells her to head home. The scene culminates with Annie leaving Ted’s opulent home and scaling the large gate at the end of his driveway (she is too much of a doormat to go in and ask him to open it for her). Once she reaches the top of the gate, straddling it like a big, white pony, it begins to move — Ted’s cleaning lady has opened it from the other side. So Annie is forced to ride the gate, in what has to be the ultimate “walk/ride of shame.” As this scene built to this wonderful visual gag, the audience was roaring, and I knew I was in for a good night.

What I liked best about Bridesmaids was the way that it mixed together different kinds of humor. Yes, it gives us Annie straddling an electronic gate, shame and humiliation radiating from her small frame. Yes, it gives us Megan (Melissa McCarthy) making fat jokes at her own expense, inviting us to laugh at her body and the possibility of its sexuality (I had some problems with this character). And yes, we see Lillian (Maya Rudolph), the beautiful bride-to-be, decked out in a gorgeous vintage wedding gown, just so that its many layers can hide her uncontrollable diarrhea. Which she makes in the middle of the street.

Beyond this easy humor (for the record, I loved the vomit/shit scene), the movie also offers humor based on the realities of women’s lives. As a mother, I enjoyed hearing bridesmaid Rita (Wendi McClendon-Covey) deflate bridesmaid Becca’s (Ellie Kemper) rosy illusions about motherhood. When Becca, a newlywed, gushes about how s “beautiful” motherhood must be, Rita enlightens her: “The other night I was making a lovely dinner for my family, and my youngest son came in and said he wanted to order a pizza. I said ‘No, we are not ordering a pizza,’ and he said ‘Mom why don’t you go fuck yourself.’ He’s 9.” Later in the film, Rita begs for a bachelorette party in Las Vegas so that she can get away from her children and wear her new “tube top.” I too have a tube top in my closet that never gets worn. Yes, this movie was definitely written by women. By funny women.

I also loved this film because it offered a great protrait of the friendships of women in their thirties — friendships that have endured so many of life’s successes and failures. In particular, the first scene between Annie and Lillian, where they sit eating brunch post-workout, reminded me of so many of my female friendships. These friendships are loud, funny, and often a bit crass. While I was a huge fan of Sex and the City and its brand of “loud/funny/crass” women, their conversations usually just reminded me that I was way less fabulous than Carrie, Samantha, Charlotte, and Miranda. I could covet their clothes and their apartments, but I was not one of them. But in their brunch scene, Annie and Lillian imitate a penis (brilliant!) and spread black cake on their teeth to make each other laugh. They also confide in each other and offer good, reassurring advice.

I loved this friendship and that’s what made Annie’s increasingly bizarre behavior throughout the film make sense. Annie has lost her business, her boyfriend, and her self esteem — her friendship with Lillian is the only great thing she has left. No wonder she becomes threatened when Helen (Rose Byrne) tries to step in as Lillian’s maid of honor and new best friend. I’m not saying that her freak out at Helen’s Parisian-themed bridal shower wasn’t over the top: but it was a little bit cathartic for anyone in the audience who has looked around at a wedding celebration and thought “Seriously?”

A few more highlights:

* We learn, early in the film, that Annie hasn’t really baked anything since her cake shop closed down. But we get one scene in which she painstakingly creates a cupcake masterpeice. We see her rolling out the marzipan, cutting and fashioning it into delicate petals, and then painting each leaf. The finished product, a single, perfect, flower-topped gem, is gorgeous. Annie stares at her masterpiece, without any sense of triumph or passion … and then shoves it in her mouth.

* While I was a little frustrated with the character of Megan (why must the plus size woman play the most buffoonish role?), I did adore the scene on the plane in which she interrogates a man (Ben Falcone) whom she believes to be a federal marshall. It’s not that their conversation was all that funny — they were discussing the pros and cons of concealing a weapon in one’s butt — but I loved that the man (played by McCarthy’s real life husband) was clearly amused, rather than annoyed, by Megan’s paranoid theories. Rather than angrily dismissing her, he engages her and asks questions about how a gun concealed in the butt could actually be practical. The scene could have been absurd, but it was playful instead. Someone could have actually had that conversation on a plane.

*Finally, Annie’s love interest, Rhodes (Chris O’Dowd), was just wonderful. I believed that a girl like Annie would fall for a guy like him (and if she didn’t, well, that would be okay too. The movie’s success does not depend on Annie’s heterosexual coupling). When Rhodes and Annie finally get to make out, after lots of sexual tension, he is so delighted that he declares, mid-kiss, “I’m so glad this is happening!” That scene made me feel happy for Annie.

In conclusion, it is very clear not just that women wrote this movie, but that jokes based on the specific experiences of women, are funny. So go fuck yourself, Christopher Hitchens. No really, go fuck yourself Christopher Hitchens. The reason why there aren’t more great, funny, female-focused films out there has nothing to do with the inherent unfunniness of women. It has to do with fears within the industry that a female-centered comedy will die at the box office. So I beg you, people: go see this movie. Show Hollywood that this is the kind of film that everyone, not just women, wants to see.

For more great reasons to see this film, check out Annie Petersen’s post here.

I’m also interested in hearing your thoughts: did you enjoy Bridesmaids and why? Or do you feel its overrated? What are some other female-centered comedies or female comedians who make you laugh?

BLACK SWAN, Cinematic Excess, and the Full Body Experience

No, I haven’t written a new blog post. January has been a crazy month! January’s been so crazy, in fact, that it has bled into February. I plan to write more in the next few months. But until then, please to enjoy my thoughts about Black Swan and the power of those icky, cuticle-pulling scenes in the latest issue of Flow TV, online now.

Click here to read.

My Popular Culture New Year’s Resolutions

I realize that New Year’s Resolutions are pretty pointless. They are the reason why I have to wait in line to use my favorite elliptical machine at the gym for the entire month of January. They are the reason why people stock up on healthy crap, like quinoa and farro, and then never ever cook it. Resolutions give people false hope that it is possible to change their change terrible lifestyle habits and grating personality ticks. I’d like to think that I’ll be a better mother/wife/daughter/sister/friend/colleague in 2011. But I will likely go on being my inadequate self, no matter how many resolutions I make.

However, resolutions that do not require me to diet, exercise more, act nicer to people I don’t like, act nicer to people I do like, or stop kicking puppies are far easier to keep. In the spirit of not making myself a better person in 2011, below I have listed my popular culture resolutions. Please to enjoy:

1. Rather than watching them in fits and starts, in 2011 I resolve to finish watching all available episodes of Dexter, Breaking Bad, and Friday Night Lights.

I tend to watch TV on DVD in the summertime, when most good television is on hiatus, or during the “slow” times, like the winter holidays. That means I tend to feast on back-t0-back episodes of a series, watching two episodes an evening for several weeks. But then, like a fickle lover, I abandon the series as soon as one of my favorite network or cable shows premieres. I have completed seasons 1 and 2 of Breaking Bad and seasons 1, 2 and 3 of Dexter. But Friday Night Lights? Poor, sweet, Friday Night Lights. We have watched you in such a piecemeal fashion that I can’t recall where we left off. Is Julie (Aimee Teegarden) dating Matt (Zach Gilford) again? Is Landry (Jess Plemons) still trying to cover up that accidental murder? Is Tyra’s (Adrianne Palicki) hair straight or curly? I am so sorry Friday Night Lights. I have neglected you and you deserve better.

2. I will make more of an effort to see movies while they are still in the theaters.

Before I had children, I went out to the movies all the time. ALL THE TIME. After the birth of my first child in 2006, I didn’t go nearly as much. And after the birth of #2 in January 2010, movie-going stopped almost entirely. I needed to be around to put the baby to bed around 7:00 pm (he is/was breastfed) which meant I could only go to movies that started at 7:30 pm or later. And due to the chronic sleep deprivation inflicted upon me by my darling baby boy, I couldn’t go to any movies that finished later than 10:00 or 10:30 pm. Indeed, I am ashamed to admit that I recently fell asleep (briefly) during a 9:20 pm showing of True Grit (2010, Ethan and Joel Coen). This means that any movie I wanted to see had to start no earlier than 7:30 pm and no later than 8:00 pm. Not much wiggle room. Not much fun for those who tried to make movie plans with me. However, in 2011 I plan to wean the baby (soon soon soon) AND teach him how to sleep through the night. Easy right? Greenville movie theater that smells like pee, here I come!

3. I will watch Firefly.

A few years ago my husband and I borrowed Season 1 of Buffy the Vampire Slayer on DVD from a friend. We loved it and proceeded to watch the next 6 seasons within one year (hey, we only had the one kid then). So when Firefly, Joss Whedon’s much-lauded follow-up project became available on Netflix Instant earlier this year, my husband suggested that we watch it. At the time we were still knee-deep in Breaking Bad episodes (see Resolution # 1), and our DVR queue was filled with shows. I simply couldn’t commit. So my husband watched it without me. Then, last semester I decided to observe my colleague’s class, a team-taught course on frontier mythology. The day I visited they were discussing Firefly. By the end of the class I realized that I had made a terrible mistake. Why didn’t I watch it with my husband? Oh the regret! You see, 90% of my TV and DVD watching is done with my husband at my side; this is our “quality time” together. So if I ever want to watch something that he does not want to watch, it is very difficult to find the time for it. But in 2011 I will make time for Firefly. Even if it means putting the kids back into their safety cages. Don’t be concerned. They like their cages.

4. I will watch more movies that are a. not new releases and b. not assigned for my classes.

There was a blissful time in my life, not too long ago, when I would sit on my couch, pen and notebook in hand, watching film after film. These were the dissertation years, when watching films all day was part of my “homework.” Sure, some of the films I had to watch were real stinkers, like Cutthroat Alley (2003, Timothy Wayne Folsome) and Teenagers from Outerspace (1959, Tom Graeff). But it was fun even watching the stinkers. However, once I started my position at ECU, I found that I stopped watching older films unless I planned to teach them in my classes. I stopped working on that list of films that all film scholars have in their heads: “The List” of films that I want to see and that I know that I need to see. So in 2011, I resolve to watch at least some of the following (Yes, I realize that there are some films on this list that I should have watched a looooong time ago. And yes, some of these are stinkers):

Eyes without a Face (1960, Georges Franju)

Thelma and Louise (1991, Ridley Scott)

Rashomon (1950, Akira Kurosawa)

Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985, George P. Cosmatos)

Red Dawn (1984, John Milius)

Summer Stock (1950, Charles Walters)

Panther Panchali (1955, Satyajit Ray)

Play Time (1967, Jacques Tati)

There are so many more films on “The List” but I want my New Year’s resolutions to be reasonable. And I am hoping that blogging about my resolutions will ensure that I stick to at least some of them. I also plan to blog about some of the films in Resolution #4 as I watch them.

5. I will stop wasting precious “screen time” on Reality TV shows with little nutritional value.

Most reality programming is the TV equivalent of McDonald’s. It’s great when you’re consuming it, but you know that at best you’ve filled your body with worthless calories, and at worst you’re gearing up for a heart attack. Don’t get me wrong: MTV’s reality shows have served me well. I have devoted many a blog post and article to The Hills, The City, The Real World and Teen Mom. And my next book project will focus on these programs and their teenage audiences. But, in 2011 I vow to cut out all “unnecessary” TV junkfood from my diet. I will not watch the revamped American Idol. I will not watch any dance competition shows. I will not watch anything in which people try to lose weight, compete for plastic surgery, or interact with a Kardashian. This is not a moral choice. There is nothing “wrong” with these shows. But if I want to keep Resolutions #1-4, then I need to trim some fat. My kids won’t stay in their cages forever.

6. Finally, and most importantly, in 2011 I will play more Angry Birds.

Because those stupid pigs won’t kill themselves.

So, what are your popular culture resolutions for the year? Remember, it is so much easier to watch a movie than exercise! Won’t you join me on the couch in 2011?

The Films that Fill Me with Dread

For me, winter break is a time to catch up on all the movies that I didn’t get to see in the theaters during the year. I had a second baby at the beginning of 2010 so “all the movies that I didn’t get to see in the theaters during the year” = “all of the movies released this year.” But don’t pity me, friends. My Netflix queue is pretty kick ass these days and I’ve really enjoyed playing catch up over the last few weeks.

Earlier this week my husband and I decided to watch a film that we had both been wanting to see for months, The Road (2009, John Hillcoat). We were at his parent’s house and had their TV all to ourselves, which is a rarity in a house where 8 people are staying. We were about 40 minutes in to the film when my husband’s sister and her boyfriend returned from a friend’s house. We chatted with them for about 15 minutes and when they headed upstairs I said to my husband “Okay, let’s finish the movie.” He replied, somewhat despondently,”Do we have to?”

You see, The Road is a real downer. It focuses on two characters, the Man (Viggo Mortensen) and the Boy (Kodi Smit-McPhee) — they are never given proper names — who spend the majority of the film wandering through a frigid, grey-toned, postapocalyptic wasteland. They are dirty, tired, and hungry. All plant and animal life has died, so food is almost non-existent. Things have gotten so bad that people have started to eat each other; in one scene the Man and the Boy happen upon a basement full of naked, emaciated human beings that are being held captive in a makeshift slaughterhouse. Good times.

The Man and the Boy do have a mission. They are heading “South” because the Man hopes that things will be “better” there. But this seems unlikely — the world is dying, after all. So their arduous, seemingly unending journey feels pointless. Yes, the Man tells his son that they must keep going because they have a “fire” inside of them, and they cannot let that fire go out. But why? Why subject your child to this living Hell? To what end? And why subject the viewer to this Hell? The Woman (the Boy’s mother, played by Charlize Theron) had the right idea when she offed herself.

Despite the crushing depression we were experiencing, we did finish watching The Road. But it was difficult. My husband and I even resorted to using coping mechanisms — like heckling the film at moments of high drama — as a way to detach ourselves from the agony. For example, at one point in the film the Man has a breakdown and begins to sob. He is exhausted. His life and the life of his child are continually being threatened. He is dying of some unidentified lung ailment. The world is coming to an end for crying out loud! Right when the emotion of this scene became too much to bear — the Man is beginning to realize that soon he will be leaving his boy alone in this awful world — my husband yelled “Oh wahhhh! Poor me!” Normally I would be annoyed that someone had broken the spell of the film, but now I welcomed it. I needed to be detached from the pain and the agony on-screen. In fact, I was so unsettled by The Road (despite its optimisitic ending), that it took me several hours to fall asleep afterwards and I was plagued with dark and troubling dreams throughout the night.

The next morning I awoke exhausted and angry with myself: why did I decide to watch this movie? After all, a few years ago I made a vow to myself that I would no longer force myself to watch movies that are mentally traumatizing. I came to this decision after watching the English-language remake of Funny Games (2007, Michael Haneke). For those who don’t know, Funny Games tells the story of a wealthy white family who heads out to their beautiful, idyllic lake house for a family vacation. They are soon taken hostage by two smiling sociopaths, Paul (Michael Pitt) and Peter (Brady Corbett), who mentally torture them before [SPOILER ALERT] killing all three of them. I knew that these deaths were going to happen from the moment I spied Paul’s smiling face and yet I continued to watch. I watched as they tied up the couple’s young son and then killed him with a shotgun. I watched as the mother (Naomi Watts) wailed over the dead body of her only child. I should have turned the film off then. But I didn’t. I kept watching because I like to finish what I start. I kept telling myself “It’s just a movie.” And then I didn’t sleep all night.

In the case of both The Road and Funny Games my sleeplessness and nightmares were not caused by fear. I wasn’t worried that a bomb would destroy the world as I slept nor did I fear that two smiling young men would break into the house and hold me and my family hostage. What kept me awake and haunted my dreams was the dread each film stirred inside of me. Both films tapped into my deepest fear — the thing that I dread more than anything else — which is a world in which I will be unable to protect my children from harm. These films exploit these feelings of dread, offering parent protagonists who try and fail to keep their children safe under extreme circumstances.

When I watch a drama, I try to sympathize with its protagonists and see the world from their point of view. If I don’t do that, then I don’t feel like I am truly experiencing the story. The directors of Italian Neorealist films like The Bicycle Thieves (1948, Vittorio De Sica) depended on this sympathy — without it their films would fail as calls to action. And in melodramas like Imitation of Life (1959, Douglas Sirk) sympathy, and the tears that flow when we realize that Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) will never be able to tell her mother that she loves her, are central to the genre’s pleasures.

However, this sympathy becomes a liability when watching a film like The Road. For example, every morning the Man wakes up, gasps in terror, and places a frantic, searching hand on the Boy’s chest. He is making sure that the Boy is still there. This little detail filled me with dread. How does the Man even sleep? How could he lie down and rest, knowing that his boy could be stolen away by a band of cannibals? Contemplating such a life, even entertaining the possibility of such an existence, is mentally overwhelming to me. And this pervasive feeling of dread lingers for days, sometimes weeks, after the film is over. For this reason I think I need to stop watching any movie in which children are put in danger or are killed. I’ve already stopped watching zombie movies for similar reasons (they give me terrible nightmares).

But banning certain movies from my life makes me sad. I’ve devoted my life to the study of film so the idea of limiting what I watch doesn’t seem right. Now I know that Kelli Marshall refuses to watch movies with animals in them. And last spring Amanda Lotz wrote a piece for Antenna about how being a mother affected her reaction to a scene from Lost. So I know I’m not alone in feeling this way. Who we are affects how we watch and what we watch. But sometimes I wish that it didn’t.

In conclusion, my experience with The Road has led me to wonder: has parenthood limited my ability to watch certain films? Can personal experiences — like my early (and traumatic) exposure to zombie movies — profoundly alter our ability to watch certain types of films? Or do I just need to suck it up?

And what about you: what films fill you with dread and why? Has this kept you from watching them? Or do you enjoy this feeling of dread? I’d love to hear your thoughts below.

Nucky Thompson: The Gangster who Won Me Over

When Boardwalk Empire premiered on September 1 of this year, I was unenthused with Terence Winter’s decision to cast Steve Buscemi in the role of the series’ central protagonist, Nucky Thompson. Traditionally the gangster hero is played by an actor (almost always male), who is formidable in stature (Vito Corleone), personality (Rico Bandello), or both (Tony Soprano). The gangster is the very definition of a “tough guy.” If he shoulder checks you on the street, you’re not going to demand an apology. The gangster inspires fear, even when he’s a puny as Little Caesar‘s (1931, Mervyn Leroy) Rico Bandello.

By contrast, Buscemi is a character actor best known for playing weaselly, neurotic, or pathetic characters. In Reservoir Dogs (1992, Quentin Tarantino) he objected to his assigned alias, Mr. Pink (“Why do I have to be Mr. Pink!”) and petulantly refused to tip his waitress, inspiring one of my favorite movie lines of all time:

Mr. Pink: [rubbing his thumb and index finger together] You know what this is? It’s the world’s smallest violin playing just for the waitresses.

In The Big Lebowski (1998, Joel and Ethan Cohen), he is Donny, one of The Dude’s (Jeff Bridges) bowling buddies. While good-natured, Donny is incredibly annoying and is often told to “Shut the fuck up!” Buscemi has a face that almost demands that it be told to “Shut the fuck up!”

Even when animated, as he is in Pixar’s Monsters, Inc. (2001), Buscemi plays Randall Boggs, a duplicitous chameleon who delights in his profession (the scaring of children), and is consumed with jealousy over the success of his rival, Sulley (John Goodman). As always, Buscemi’s character fails to master his bigger, smarter, braver and, almost always, better looking, foes.

As a fan of Buscemi’s work, this is how I like him. He is a “character actor,” after all. Character actors, by definition, are not the leading men. They are there to support, antagonize, or bewilder the leading men. Thus, I was surprised to hear that he was cast as the lead in a television series. A movie only demands that an actor be charismatic for 2 hours but a television series asks that actor to command the screen week after week. As I watched the opening credits of Boardwalk Empire, which, like The Sopranos, features its protagonist taking stock of his domain, I was doubtful:

Buscemi stands on the beach, looking like something out of a Magritte painting; he appears stylized and inscrutable, devoid of the fire and passion I expect of my gangster heroes. “This is not going to work,” I sighed to myself.

After the first few episodes of the series, I believed that I was right. A gangster story is only as good as its hero, and Boardwalk Empire lacked one. Nucky seemed too calm, too polite, too contained, too un-Buscemi-like, to carry the series. In his seminal piece on the genre, “The Gangster as Tragic Hero” (1948), Robert Warshow argued that “[t]he gangster’s whole life is an effort to assert himself as an individual to draw himself out of the crowd, and he always dies because he is an individual.” Thus, Nucky’s seemingly reasonable demeanor stands in stark contrast to one of the gangster hero’s central qualities: his excessive nature. The gangster’s outsized desires and ambitions are what lead to both his success as well as his demise.

Nucky, by contrast, appears to be a conciliatory man. He gives money to anyone who asks for it, endures back talk from his ward/employee, Jimmy Darmody (Michael Pitt), and wines and dines politicians whose piggish desires clearly disgust him. We don’t see Nucky lose his cool, punch a disrespectful underling, or accidentally kill anyone (as say, Tony Soprano might do). What kind of gangster hero is that?

But as I continued to watch the series I realized that Nucky was a great gangster hero and that Buscemi was nailing the role. While other gangster heroes are defined by their unbridled passion, their inability to contain their desires and emotions (such as Tom Powers’ suicidal decision to avenger his best friend’s murder in Public Enemy), Nucky’s power lies in his ability to be in control at all times. And given Buscemi’s small, 5 foot, 9 inch frame, such control makes sense. A Tony Soprano can throw a punch when he likes, but a little man like Nucky would invariably fail as a physical aggressor. Instead, Nucky must rely on his intellect and reason in order to remain dominant.

This quality is best exemplified in the finale, when Jimmy, who has recently discovered the role Nucky played in the procurement and rape of his mother at age 13, confronts Nucky at a party. Jimmy is not just angry about the abuse his mother endured, he is also hurt to discover that Nucky took care of him out of an obligation to the Commodore (Dabney Coleman), rather than out of love. Jimmy always saw Nucky was a father figure but he now realizes that Nucky just viewed him as another item on his long to-do list. When Jimmy directly poses this question to Nucky, the aging gangster responds, “What difference does it make?” Nucky seems almost perplexed by Jimmy’s anger, as if the love between a father and a son is incomprehensible to him. And given Nucky’s abusive relationship with his own father, it probably is.

Just because Nucky appears controlled on the outside does not mean the man is not excessive. He is just adept at having others enact his excess for him. For example, when Nucky discovers that Margaret Schroeder’s (Kelly MacDonald) husband, Hans, has beaten her to the point that she has a miscarriage, he decides to have the man killed. But Nucky’s decision proves to be dangerous to his empire. It attracts the interest of Federal Agent Nelson Van Alden (Michael Shannon), who is sure that the murder is somehow linked to Nucky. We only find out in the finale that Nucky’s decision to have Hans killed was based purely on emotion; his son died when he was just a few days old and therefore the death of any baby strikes a nerve. Even when telling this story to Margaret, Nucky’s emotions are barely visible, registered in the twitch of his lips or perhaps a moment when we can detect tears in his eyes. But only for a moment. Then he shakes it off and once again becomes “Nucky Thompson.” For this reason, one of my favorite moments of the season was when Nucky burned down his father’s home. It was so out of character for him, but also very revealing of the emotions he normally keeps buried.

Nucky must reign in his emotions and dispassionately govern those around him in order to maintain his power. The few moments when he does slip up and allow his emotions to take over, such as the murder of Hans, are the cause of most of his problems. Indeed, his hasty to decision to fire his brother Eli (She Wigham) will likely prove to be his greatest mistake yet: the finale closes with Eli, Jimmy, and the Commodore conspiring to oust Nucky from his seat at the top of the Boardwalk Empire.