Film

BADLANDS: The Film I Always Find a Way to Teach

Whenever I meet new people and they discover that I teach film for a living, they invariably ask me: “So what’s your favorite movie?” I realize that this is polite, small talk kind of question. It’s the kind of question people think that they are supposed to ask me. But to someone who has devoted their livelihood to researching, analyzing, and teaching about moving images, the question is agonizing. Asking me what my favorite movie is is like asking me: “Which of your children do you love the most?” There is simply no way for me to answer this question in a satisfying, honest way. So I usually tap dance around the answer, trying all the while to not sound like a pretentious academic douchebag (which is what I am). “Oh it’s so hard for me to choose!” I say. When the asker looks sufficiently annoyed, I usually submit and say something expected like “Casablanca. Casablanca is my favorite movie” Then they leave me alone.

But the real answer to the question “What is your favorite movie?” is very complex for me. I love different movies for different reasons. I love Double Indemnity (1944, Billy Wilder) for its whipsmart, sexy dialogue. I love The Crowd (1928, King Vidor) for its winsome, bittersweet ending. I love Magnolia (1999, Paul Thomas Anderson) because it was the only movie to figure out the exact kind of role that Tom Cruise should play. I love The Breakfast Club (1985, John Hughes) because I watched it pretty much every Saturday afternoon on TBS when I was 12 and didn’t realize that they weren’t smoking cigarettes during that one scene in the library. I love American Movie for so many reasons but especially because of this scene:

And I love Terence Malick’s debut film (his DEBUT!), Badlands (1973), because it is, for lack of a better word, a perfect movie. Badlands is a movie that I never tire of watching. I get giddy about the opportunity to introduce it to new people. For that reason, I try to put Badlands on my syllabus whenever possible. In fact, this week I screened Badlands for my Film Theory and Criticism students for our unit on film sound. I love teaching this film because, as I mentioned, it’s perfect, and most students have not heard of it. Therefore, after the screening students generally exit the classroom with the same dazed, but happy, expression I had after I watched it for the first time.

So what makes Badlands a “perfect” movie?

Terence Malick’s Script

In the very first scene of the movie we see Holly, a 15-year-old girl (Spacek was 24 when she played the role) with red hair, freckles, and knobby knees. She is playing with her dog on her bed. It is a scene of innocence, of total girlhood joy. But this happy, carefree image contrasts with Holly’s vacant, flat, voice over, which informs us “My mother died of pneumonia when I was just a kid. My father kept their wedding cake in the freezer for ten whole years. After the funeral he gave it to the yard man. He tried to act cheerful but he could never be consoled by the little stranger he found in his house.” In four brief lines Holly aptly summarizes her childhood: she was an only child; her father was once a real romantic (he kept his wedding cake in the freezer for 10 years after all) but the untimely death of his wife deadened his heart (he gave the cake to the yard man after his wife’s funeral); Holly and her father are unable to connect emotionally (Holly knows that her father sees her as a “stranger”). Such is the mastery of Malick’s tight script — not a word is wasted.

Malick’s script is also admirable in that he was able to capture the rhythm and the texture of a teenage girl’s stream of consciousness. Holly doesn’t speak like an adult and she doesn’t speak like a child. After Kit kills Holly’s father he instructs her to grab her schoolbooks from her locker so that she won’t fall behind in her studies. Holly’s voice over then tells us “I could of snuck out the back or hid in the boiler room, I suppose, but I sensed that my destiny now lay with Kit, for better or for worse, and it was better to spend a week with one who loved me for what I was than years of loneliness.” If these words were in Holly’s diary they would probably be adorned with hearts over the i’s and little flowers scribbled in the margins.

Holly’s Voice Over/The Stereopticon Scene

There are so many scenes I could point to that illustrate the genius of Sissy Spacek’s line readings in this film, but my favorite is the much-lauded stereopticon scene. After killing Holly’s father the couple flees to the woods and build themselves a Swiss Family Robinson-style tree house (though it is likely that the grandure of this house has been imagined by Holly). In the middle of this segment, Holly sits down to look at some “vistas” in her father’s stereopticon. This is the first time that Holly has mentioned her father since his murder and yet she still does not mention if his death bothers her. As Holly looks at travelogue images of Egypt and sepia-toned lovers, she waxes philosophical, in the self-involved way that only a 15-year-old girl can. As she looks at an image of a soldier kissing a morose young woman she wonders “What’s the man I’ll marry look like? What’s he doin’ right this minute? Is he thinking about me now by some coincidence, even though he doesn’t know me?” As the camera slowly zooms in on this particular image Holly asks, the excitement barely rising in her quiet voice “Does it show in his face?”” The non-diegetic music becomes more intense as the scene progresses. Holly is coming to an epiphany. She is just some girl, born in Texas, “with only so many years to live.” She is aware that her life is structured by a series of accidents (her mother’s death), and yet, that life is also fated (“What’s the man I’ll marry look like?”). This voice over indicates that Holly is able to see her role in the larger web of humanity, and yet, this same girl watches as her boyfriend shoots her father and random unfortunates who happen to cross their path. It is infuriating and chilling. In fact, every time I watch this scene I get chills.

Kit/ Martin Sheen

I can’t say that I know much about Martin Sheen’s body of work, other than his roles in Apocalypse Now (1979, Francis Ford Coppola) and Wall Street (1987, Oliver Stone). I do know, however, that Martin Sheen frequently mentioned that Badlands was his best work. And I’ll take his word for it. Sheen is amazing in this role. He plays Kit as a man in limbo, a study in contradictions. He lectures Holly about the dangers of littering (“Everybody did that, the whole town’d be a mess”) but shoots her father without comment. He fancies himself a man of ideas, but when given the opportunity to speak, he has nothing to say. Kit wants to be a rebel, like his idol James Dean, but he speaks in platitudes.

Kit is constantly wavering between two poles. Sheen could have therefore played Kit as a bipolar monster — a man who shifts from one personality to the next. But instead, he makes Kit’s duality into an integrated whole. He plays Kit as a man who does not know who he is or what he should do; he only knows that he must fully commit himself to whatever choice he makes. For example, after Kit has been arrested he is allowed to speak with Holly briefly. Kit boasts “I’ll say this though, that guy with the deaf maid? He’s just lucky he’s not dead, too.” Then, in the same breath he tells Holly “Course, uh, too bad about your dad…We’re gonna have to sit down and talk about that sometime.” These moments are almost comical. Indeed, my students often laughed at Kit’s antics, even when he was shooting people.

The Music

I am incapable of talking about film music in a useful way. I can only ever use vague words like “haunting” or “tense” to describe a score. But there is something … haunting … about the non-diegetic tracks used in Badlands, such as the angelic, choral music that plays as Holly’s childhood home is consumed by fire:

So I suppose the next time someone asks me what my favorite movie is, I should just say “Badlands.” It wouldn’t be true, of course. As I mentioned, I could never pick just one. But it’s a movie that represents everything I love about movies: beautiful cinematography, impeccable acting, a tight script. And those chills.

MACHETE: Camp Deluxe

Machete was not a movie that I planned to see this summer. Films like Inception, The Kids are Alright, Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, and even Piranha 3-D (yes, really) were higher on my to-do list. But there were several factors that drove us into the arms of this film: the movie theaters in Greenville do not hang on to independent films for more than a week (Get Low we hardly knew ye). In fact, if a film does not contain explosions, fart jokes, boobs, or talking animals, it probably won’t even make it to Greenville; I could only go to see a movie that was over by 10 pm (the 8 month old is still not a stellar sleeper); and finally, my husband and I had wrangled us a babysitter. So, no matter what, we were going to see a movie dammit. And that was how I found myself sitting in a darkened theater, watching Machete last Saturday night.

Almost immediately Machete, yet another entry in Robert Rodriguez’s canon of Mexploitation films, won me over. I’m a sucker for exploitation films. Indeed, the opening credits were a perfect replica of low-budget 1970s blaxploitation films: an animated title card pronouncing our hero’s name (MACHETE!), and then a simple listing of the credits. Then there was the music. Blaxploitation films often featured cohesive soundtracks written exclusively for the film, and which acted as a Greek chorus, commenting on the action in the film, praising or scolding the hero, and making future predictions. Machete‘s thumping, rock n’ roll/mariachi band hybrid soundtrack was composed by Chingon. They sing about the film’s hero (Danny Trejo), providing him with his own personal soundtrack. Hell, the “Machete Theme” makes me want to pick up a machete and kick some ass, and I’m just some lame white lady.

In addition to having his own soundtrack, Machete resembles his blaxploitation ancestors in his uncanny ability to punch, kick, shoot, and of course, slice his way through any fight with barely a scratch. At one point in the film Machete is offered $500 to participate in a street fight with a shirtless thug who has just pummeled the life out of his latest opponent. Machete consents, but continues to hold onto the burrito he has just purchased. As his increasingly annoyed opponent swings and jabs, Machete calmly dunks, swerves and chomps on his lunch. The fight ends when Machete dodges a punch in a such a way that his opponent ends up punching a rafter and breaking his arm. Machete wins the fight without ever raising his fist. Finally, as in blaxploitation films, the villains of Machete are unequivocally evil. Von (Don Johnson!) shoots a pregnant Mexican woman in the stomach to prevent her from giving birth on American soil while Torrrez (Steven Seagal!) decapitates Machete’s wife as he is made to watch. By tying this evil to the heated emotions surrounding contemporary immigration debates, the character of Machete effectively gives filmic form to the revenge fantasies of countless, enraged (and terrified) illegal immigrants living in the United States, much as Sweetback (Melvin Van Peebles) “sticking it to the Man” in Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song made contemporary black audiences stand up and cheer back in 1971.

Where Machete differs from blaxploitation, however, is in its self awareness. Blaxploitation films were, for the most part, quite earnest. When Superfly tells The Man “You don’t own me pig!” by golly he means it. Machete contains lines like these — my favorite being “We didn’t cross the border! The border crossed US!” But they are always delivered with tongue planted firmly in cheek. Nevertheless, Machete is self-aware without being a full on parody. The film wants us to laugh, but doesn’t hit us over the head with its humor. This is a delicate balance to achieve, and one of the film’s primary achievements. For example, in the film’s best visual gag, Machete is being treated in a hospital. The attending doctor and nurses start discussing anatomy, leading one of the nurses to state “So you mean the human intestines are 80 feet long?” This statement is made in the great Chekhovian tradition of “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired.” Indeed, moments later Machete’s enemies storm the hospital. The doctor informs Machete that his only means of escape is through the window, which is approximately 80 feet above the ground (wait for it…). As Machete hacks his way through the crowd of baddies (with a grotesque weapon assembled out of medical-grade knives, natch), he disembowels one unlucky fellow, grabs hold of his intestines and then leaps out of the window. It took about 20 seconds for the audience to comprehend what had just transpired on-screen and then? Raucous laughter.

There were many scenes like this in Machete — violent, disturbing scenes — that provoked the audience’s laughter. What a strange and liberating feeling — to laugh at something which would normally provoke disgust or terror. This switching of affect highlights Machete’s status as pure camp. The term camp comes from the French word “se camper” which means “to posture or flaunt.” To be camp, a film must be extraordinary in its aims. It must be flamboyant and theatrical. Why have your hero behead one man when you can have him behead three at once (and filmed in a stunning aerial shot)? Why have your hero use a machine gun when you can attach that machine gun to a motorcycle flying through the air?

Susan Sontag argues that to be pure, camp must be naive. Camp must love itself passionately but be blind to its own missteps. Camp takes itself seriously but cannot be taken seriously. By contrast, most film parodies disparage their subjects, revealing a contempt for them. Sontag does admit that on a few rare occasions (as in the work of Oscar Wilde) camp can be self-aware. I would add Machete to that short list of self-aware texts that are also camp. Rodriguez knows that his film is farce, yet he is never contemptuous or disparaging. He films Machete with a real love for the character. We can tell that Machete is Rodriguez’s hero too.

Here are some of the great camp moments in the film:

1. Two words: Linday Lohan. At this point in her career, Lindsay Lohan has become the ultimate in camp. She is pure artifice, a replica of Hollywood celebrity. Like a lamp that is shaped like a woman’s leg, Lindsay is what she is not. Every time her image appears on-screen it screams “Lindsay Lohan!” or better yet “LINDSAY LOHAN!!!” And she is therefore a perfect choice to play April, the strung out, adored daughter of Machete’s nemesis, Booth (Jeff Fahey).

2. In the film’s only gratuitous sex scene, Machete agrees to engage in a threesome with April and her mother, June (Alicia Marek). And yes, those names are used, but not abused, to hilarious effect. When the women reveal their breasts –as is the custom in gratuitous sex scenes — it is clear that April is being played by a body double. Even the hair is different. There is no reason why Lindsay Lohan should be shy about revealing her breasts — she’s done it before. So this moment exists more as a nod to the camp films of yore, where little care was taken with disguising body doubles or with correcting obvious mistakes. It is also a tease to the audience “Did you come to this movie to see Lindsay Lohan topless? Too bad for you!”

3. Every character in a camp film must appear in quotation marks. When that character appears on-screen we must instantly know what that character embodies. Thus, Machete is “Machete.” Machete becomes myth/archetype/folk hero within the first few minutes of the film when he and his partner storm a house where a kidnapped woman is being held. Machete slams his foot on the gas and drives through a throng of machine guns. The bullets ricochet through the car, making contact with his partner. By the time Machete has driven his car through the wall of the house, his partner is bloodied mess (and very, very dead). Machete, however, is fine. Because he is “Machete.” In fact, when Agent Sartana (Jessica Alba) does a background check on the hero, she discovers, among other details, that his birth name is “Machete.” Of course it is.

4. Camp is all about exaggerated sexuality: highly feminine femininity and highly masculine masculinity. Woman is “woman” and man is “man.” Thus, throughout the film, Agent Sartana wears stiletto heels, despite the fact that she is often chasing bad guys around and shooting weapons. She even uses one of her heels as a weapon later in the film. Sartana also researches the internet while taking a steamy shower (and with full make up on). Who has a computer hooked up in their shower? I would not have been surprised if she were wearing stilettos in the shower. And I won’t even mention the secret agent featured in the opening scene who hides a cell phone in her vagina because she is naked and has no other place to put it. Oops, I guess I did mention that. Sorry.

Camp taste is a mode of enjoyment and appreciation rather than judgment. Camp is not mean, but loving. Rodriguez clearly loves his subject: exploitation films, grindhouse cinema, seedy border films, and revenge fantasy flicks. He does not want us to laugh at the silliness of these film. Instead, he invites us to celebrate them in their excessive glory. As I watch Danny Trejo slice his way through bodies, fashion deadly weapons out of objects he finds around him, and make out with Jessica Alba while driving a motorcycle, I am not incredulous. The film tells me “I am silly but I am wonderful. Don’t judge me! Enjoy me!” And I did.

The Thrill of the Final Image

Somewhere in TV Land Jersey Shore‘s Snooki is carrying around an entire suitcase of bronzer. Nothing but bronzer. Elsewhere, Mad Men‘s Sally Draper may or may not be developing a nasty little eating disorder. And on True Blood Tara just smashed a vampire’s head flat with a medieval mace. I itch, no I yearn, to blog about these programs. But I haven’t. Because my Big Deadline–August 31–approaches and I must focus my energies on meeting this Big Deadline. For the next 4 weeks all intellectual activity must be channeled towards the Big Deadline.

But my Twitter pal, @KelliMarshall, has managed to distract me with this engaging meme. I could not resist. Damn you, Kelli.

Here are the rules:

The person tagged is to submit a gallery of images that represents “the thrill of cinema,” however s/he interprets that phrase. The other rules are spelled out thusly:

- Pick as many pictures as you want, but make them screen-captures.

- Pick a theme, any theme.

- You MUST link to Stephen’s gallery and my post too.

- Tag five blogs. \\ I am tagging the following (primarily) film studies blogs: Jamais Vu, The Lesser Feat, Ludic Despair and The Chutry Experiment. No pressure folks, just giving you the option to participate.

There is so much that thrills me about the cinema. But to convey that thrill with still images, when, as we all know, the cinema is about moving images, makes this meme a little more challenging. However, I have always been a sucker for the images that appear in the last few minutes of the film. These are the images that you just can’t shake. You replay them in you head long after the end credits have rolled. They are the images that have a visceral impact on the viewer.

They reach into your chest and squeeze your heart so tightly you can barely stand it:

Or they make the little hairs on the back of the neck stand on end, especially when you’re lying in bed, in the dark, all alone:

These are the images that can change the entire meaning of a film, or simply hammer home its main themes:

Occasionally , it’s not a final image that gets me, but a sound. At the end of I am a Fugitive from a Chaingang (1932, Mervyn LeRoy), Helen (Helen Vinson) asks her perpetually on the run fiance, James (the incomparable Paul Muni), what he will do to survive. “How do you live?” she implores as James slips back into the shadows. As the frame fills with darkness we hear him hiss “I steal!”

I could go on and on here but like I mentioned: Big Deadline.

Whatr are your favorite final images and why?

The D2D Release: Notes on a Burgeoning Market

Yes, it’s true, my blogging has decreased precipitously over the last three months. I had a second child and he takes up all of my time, what with his eating and pooping and inability to sit up on his own. But I did recently finish one last article for the online journal, FLOW on the subject of Direct to DVD releases. In it I argue that the study of direct to DVD films (D2D films) offers an important contribution to the fields of both reception and genre studies. If you’re a fan of such classics of Hood of tha Living Dead or Leprechaun 5: Leprechaun in the Hood, then my friends, this is the article for you.

You can click here to read the article. And for those of you still reading my blog, thanks and I promise to post more frequently in the coming months.

Why AVATAR Makes Me Feel Like an Old Russian Man

Back in graduate school I read a short essay , written in 1928, by three Soviet filmmakers, Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov. In it, the men worry about the effect that newly developed sound technology would have on the future of the cinema. They fear, for example, that “…misconception of the potentialities within this new technical discovery may not only hinder the development and perfection of the cinema as an art but also threaten to destroy all its present formal achievements.” When I read this I remember thinking that these men probably felt pretty silly by the mid-1930s, when it was clear that sound had not in fact destroyed the artistry of the cinema, but greatly enhanced it. Certainly, early sound films like The Lights of New York (1928, Bryan Foy) did suffer from stilted camera work (since noisy cameras were encased in bulky, sound-proofing boxes) and immobile actors (who crowded around microphones hidden around the film set), but the industry quickly adjusted to the new technology and rebounded. As much as I enjoy a good silent film (Sunrise [1927, FW Murnau], The Crowd [1928, King Vidor], The Playhouse [1921, Buster Keaton]) I greatly prefer sound films (bad film professor!). Technology is good.

However, with the release of James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) I feel a lot like Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Alexandrov must have felt back in 1928. I am suspicious. I am grumpy. I am a naysayer. Now let me state right off the bat that I have not yet seen Avatar. Part of that has to do with the fact that I just had a baby and part of it has to do with the fact that I am fed up with hearing about this film and its status as an industry “game changer.” In the weeks leading up to its release I couldn’t pick up an entertainment magazine or click on a film blog or turn on the radio without reading or hearing about Cameron’s technological marvel.

But it wasn’t the overhyping of the film that bothered me so much as it was the endless stream of reviews that stated that the film was visually stunning but lacking in story. The New York Daily News writes “‘Avatar’ clears the hurdle in terms of being optical candy. Its story, though, is pure cheese.” And Salon.com‘s Stephanie Zacharek says,

“The movie was made, and is designed to be seen, in 3-D, and no matter what anyone — particularly the movie’s studio, 20th Century Fox — tries to tell you, the technology and not the story is the big selling point here: If a less famous and less nakedly self-promotional director had made the exact same story with a bunch of actors in blue latex, the Fandango ticket sales wouldn’t be going through the roof.”

At the risk of sounding like those grumpy old Russians, I have to agree with Zacharek. CGI and 3-D technology should enhance a film, not be its primary draw. Avatar may represent the “future” of filmmaking — as so many bloggers, critics and Cameron himself have claimed — but what about the story? The acting? Are these things not important?

Yesterday the Academy Award nominations were announced and Avatar received a whopping nine nominations. I expected nods for Art Direction and Special Effects, but Best Director and Best Picture? What exactly is being rewarded here ? Shouldn’t Best Picture reward the achievement of the film as a whole, rather than its (spectacular) parts?

Of course, even as I write this I realize that I may be the one in the wrong. Even if Avatar‘s story and dialogue are as cheesy and derivative as the film’s detractors claim, does that mean the film should not be recognized for those things it does exceptionally well? After all, I adored Up in the Air (2009, Jason Reitman) for its clever dialogue, subtle acting and emotionally engaging story, but the film’s actors are rendered through simple camerawork, not motion capture technology. And as far as I know, Up in the Air is not playing in 3-D anywhere.

I’m not being facetious here. Perhaps motion capture and 3-D are the future of filmmaking, a technology which, like the invention of sound, will soon enhance, rather than limit the artistic possibilities of the medium. Rather than a novelty these technologies will become integral to the medium.

So while I vowed to never go see Avatar, I’ve decided that it is time to go (just as soon as I pump enough milk to allow for a 3 hour trip to the movies without the newborn). After I see it I will revisit this post and determine if my grumpy, Luddite view of the film is warranted. In the meantime, for those who have seen Avatar: Did it deserve 9 Academy Award nominations? Is it worth the hype? Is it the best picture of 2009? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

The Best Films of the Decade

Yes my friends, I took a hiatus from blogging for a while. Between end of the semester grading and other professional commitment, as well as my family’s raucous Chrismakkuh celebrations, there simply was not any time. These are my excuses, anyway, for producing a “best of the decade” list weeks after you ceased having the desire to read such arbitrary lists. My bad, ya’ll.

Still there? Okay then, before you read, you should know a few things:

1. I spent much of the 2000s with my DVD/VHS player, dutifully watching non-contemporary films as part of my Film Studies degree. Consequently, I did not see nearly as many new releases as I would have liked.

2. I am not a big fan of blockbuster/franchise films, so I refuse to put any of The Lord of the Rings films on a “best of” list.

3. I favor films with a melancholy bent because I enjoy a good cry.

Now here, in no particular order, are my favorite films from the last 10 years:

Brokeback Mountain (2005, Ang Lee)

To me this is a near perfect film. Flawless cinematography (I am thinking of long shots of white sheep running up the side of a green slope), intelligent mise en scene (the slow death of Anne Hathaway’s sexuality is marked by her ever-blonder coif and increasingly talon-like nails) and a spare script. And then there’s the cast. Everyone in this film was wonderful, but the stand out was, of course, Heath Ledger, who plays Ennis as a man whose desires are so tamped down that he literally swallows his own words before uttering them. When Ennis embraces Jack’s denim shirt in the film’s final scene, it’s a moment that rips your heart apart. Timely, beautiful, perfect. Fuck Crash (2005, Paul Haggis). Yeah, I’m still bitter.

Amelie (2001, Jean-Pierre Jeunet)

Overly precious at times? Sure. But it’s irresistable in its preciousness. One of my favorite sequences occurs early in the film, when the narrator explains the little things in life that Amelie enjoys: “Plunging her hand deep into a sack of grain, cracking creme brulee with a teaspoon and skimming stones on the Canal St. Martin.” Here we are treated to a dizzying, high angle shot of the canal which sweeps over Amelie (Audrey Tautou) as she squats on a bridge to skip stones. Little moments like that take my breath away.

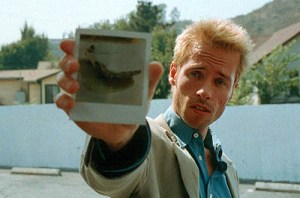

Memento (2000, Christopher Nolan)

Trapped in the head of Leonard (Guy Pearce), who lost his short-term memory after the traumatic murder of his wife, we experience life as he does — en medias res. We, like Leonard, find ourselves in the middle of situations — at one point Leonard finds himself running and doesn’t know if he’s being chased or the one doing the chasing — that only make sense when we move backwards and retrace our steps. Luckily, Leonard has a “system”–tattoos, notes, reminders placed around his abode. Yes, it’s a gimmicky concept for a film, but what always grabbed me about Memento is how it provides such a useful allegory for the mourning process. Leonard’s unceasing drive for revenge is a sublimation of his desire to work through the trauma of his wife’s death. At one point Leonard explains “I don’t even know how long she’s been gone…I lie here not knowing how long I’ve been alone. So how can I heal? How am I supposed to heal if I can’t feel time?” See, now I’m all shivery.

Once (2006, John Carney)

I’ll be totally honest: this movie could have been total crap and it would still be on this list as long as it retained its glorious, haunting soundtrack. But thankfully, Once isn’t crap. On the one hand it’s standard musical fare: a heart-broken guy (Glen Hansard) and a lonely girl (Marketa Irglova) have a meet cute (he’s singing on the streets, she needs her vacuum cleaner fixed) and discover that they make beautiful music together. Really, really beautiful music. What is wonderful about Once though, is how seamlessly musical numbers are woven into the fabric of the diegesis. Every time the guy and the girl (they are never given proper names) open their mouths or tickle the ivories, it makes perfect narrative sense. And when they sing “Falling Slowly” in the middle of a piano store, their voices tentatively coming together for the first time, it’s absolutely magical. I’m talking full goosebumps. I should also add that, next to this year’s Up in the Air, Once contains one of the most realistic and refreshing conclusions to a love affair that I’ve seen in years.

Adaptation (2002, Spike Jonze)

Adaptation is a film about, well, adaptation: cinematic, biological, and social. Charlie Kauffman (Nicholas Cage) is asked to adapt Susan Orlean’s novel, The Orchid Thief, into a splashy screenplay and it is his struggles to do so that create the fascinating film we watch. A skewering of Hollywood, a meditation on passion (and its absence), and, weirdly, an action adventure story, Adaptation is Kauffman’s most inventive script to date. And as a result of his performance in this film Nic Cage has an eternal free pass to make shit, which he continues to do with impunity.

Half Nelson (2006, Ryan Fleck)

In his best screen performance to date, Ryan Gosling plays Dan Dunne, an idealistic Brooklyn teacher trying to teach History to his primarily African American and Hispanic middle school students. Dan cares about teaching and about his students. Dan believes he can make a difference. Sound like a cliché yet? Oh right, there’s one more thing: Dan’s got a wicked crack addiction. When a favorite student, Drey (Shareeka Epps), catches him smoking crack in a school bathroom, the two form an unlikely alliance. Drey wants Dan to stop doing drugs and Dan wants Drey to stay out of the drug trade. Both ultimately let each other down. The film is equally effective as a parable about the frustrations and despair of the political Left and as a portrait of America’s failed school systems.

Royal Tenenbaums (2001, Wes Anderson)

There are so many things to love about this movie: the deadpan narration by Alec Baldwin, the quirky cast, the soundtrack. But best of all is the mise en scene. Every shot in the film is crammed with details — Henry Sherman’s fastidious bow-ties (Danny Glover), Margot Tenenbaum’s (Gwyneth Paltrow) bookshelves crammed with slim plays, and the endless rows of Richie’s (Luke Wilson) framed drawings, dutifully hung by his adoring mother (Angelica Houston). Yet despite it’s loopy surface, the film is filled with moments of deep human connection. One of my favorite scenes in the film is an exchange between Chas Tenenbaum (Ben Stiller) and his future step-father, Henry. Over the course of the film we learn that Chas reacts to his wife’s untimely death, not by mourning, but by keeping his two young sons on a short leash — expecting the next disaster to strike at any moment. Rather than break down, he takes control. On the day of his mother’s marriage to Henry, a union Chas has opposed through much of the film, Chas is confused to discover that Henry has an adult son named Walter (Al Thompson). Henry has to remind Chas that he has been married before and that his wife died. He is a widower. As Henry, Walter and Richie adjust their ties in the mirror, Chas approaches the group of men and begins to adjust his own tie as well. He then announces, as if the news were completely new, “You know, I’m a widower myself.” Henry pauses, turns towards Chas, and places his hand on his shoulder “I know you are, Chas.” It’s a simple exchange, a throwaway moment, but it grabs me every time.

Old Boy (2003, Chan-wook Park)

If someone kidnapped you and kept you imprisoned in a bland apartment for 15 years with only a television for company and the same dumplings to eat day after day, you’d be pretty pissed off, right? Old Boy follows Oh Dae-Su (Choi Min-sik), businessman-turned-martial arts expert, as he seeks revenge for his years of imprisonment, and boy is he mad! The film is riddled with graphic violence but my favorite scene by far is the infamous “hammer scene” in which a wounded Dae-Su fights a horde of men with nothing but a hammer. Here the fighting is lugubrious and painful, men groan and creep and fall. And the best part is that Park films it in one long take like a slow, bloody waltz.

Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003, Quentin Tarantino)

I have always been critical of Tarantino’s reluctance to engage in the necessary task of editing his films. For me, Inglorious Basterds (2009) was long and flabby. Kill Bill: Vol. 1, on the other hand, felt just right to me (perhaps because Tarantino had to cleave the film into 2 volumes?). I suppose I’m a sucker for films in which women are given meaty, kick ass roles. How can you not love a film in which Uma Thurman informs the survivors of a massacre created by her own hands, “Those of you lucky enough to have your lives, take them with you. However, leave the limbs you’ve lost. They belong to me now.” Kick. Ass.

Grizzly Man (2005, Werner Herzog)

Using the 100 hours of footage that Timothy Treadwell, aka, the “Grizzly Man,” left behind after his brutal death, Herzog attempts to make sense of the man’s seemingly insane desire to live among wild bears. Was Treadwell crazy? Probably. But this is not the only message of the film. Treadwell was also a man filled with passion and love. The film could have been exploitative, but it’s not. It’s simply sad.

Up in the Air (2009, Jason Reitman)

Critics have been stumbling over each other to praise this movie, but for once the praise is deserved. As so many have already noted, Up in the Air is a timely portrait of today’s dire economic climate. As I sat in the darkened theater, listening to real Americans explain how losing their jobs was going to impact their lives and their families, I couldn’t help but think of all the people I know right now who have lost their jobs, have had their hours cut or who simply cannot find work. But then,oddly enough, the film also soars as a romantic comedy. The rapport between Ryan Bingham (George Clooney) and Alex (Vera Farmiga), two commitment-phobes addicted to air travel and impersonal hotel rooms, is honest and funny. And can we talk about George Clooney for a minute? Every look, every gesture, every half-smile was perfect. Take the scene at Ryan’s sister’s wedding reception. In a few dialogue-free shots we see Ryan’s walls come crashing down. We can actually see him falling in love (0r what he believes to be love) with Alex. And then there’s Natalie Keener (Anna Kendrick), who was truly wonderful as a smart, ambitious young woman who realizes, as most of us do around the age of 23, that the “grand plan” we had for ourselves in college doesn’t really translate in the real world. Finally, the film’s ending (I promise, no spoilers here) was the perfect balance between realism and idealism, despair and hope. It’s the kind of film that makes you appreciate your own very heavy backpack.

And the rest:

Lost in Translation (2003, Sofia Coppola)

Thank you Ms. Coppola, for not letting us hear what Bob (Bill Murray) says to Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson).

American Splendor (2003, Shari Springer Berman)

Paul Giamatti is a god.

District 9 (2009, Neil Blomkamp)

A science fiction social problem film turned explode-y action adventure film. I was literally on the edge of my seat throughout the entire film. Then I bawled like a baby. I’m not sure that’s ever happened before.

City of God (2002, Fernando Meirelles)

This film is noteworthy for its stunning cinematography and kinetic editing alone, but it’s translation of the classic gangster formula to the slums of Rio de Janeiro is what makes this one of the stand out films of the decade.

This film is noteworthy for its stunning cinematography and kinetic editing alone, but it’s translation of the classic gangster formula to the slums of Rio de Janeiro is what makes this one of the stand out films of the decade.

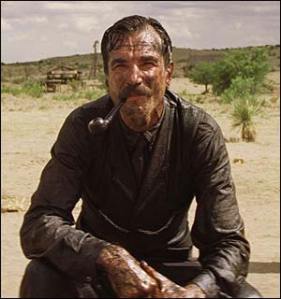

There Will Be Blood (2007, Paul Thomas Anderson)

Dirty, greasy and bloody. If movies had an odor, There Will Be Blood would smell like sweaty men and rust. I drink your milkshake!

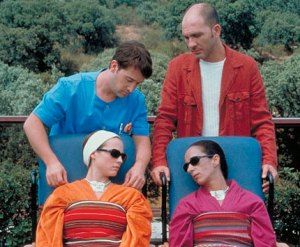

Children of Men (2006, Alfonso Cuaron)

OK, I’ll admit it: My husband and I watched this one with English sub-titles because we found the British accents too difficult to understand. And we still loved it. So there.

Talk to Her (2002, Pedro Almodóvar)

You have to love a film containing a beautifully shot, black and white silent film, “The Shrinking Lover,” depicting a tiny man and an enormous vagina. Enough said.

Brick (2005, Rian Johnson)

Sure, you all fell in love with Joseph Gordon-Levitt in 500 Days of Summer (2009, Marc Webb). But I fell in love with him here, spouting hard-boiled lines like “Throw one at me if you want, hash head. I’ve got all five senses and I slept last night, that puts me six up on the lot of you.”

Shaun of the Dead (2004, Edgar White)

Knocked Up (2007, Judd Apatow)

Debbie (Leslie Mann): I’m not gonna go to the end of the fucking line, who the fuck are you? I have just as much of a right to be here as any of these little skanky girls. What, am I not skanky enough for you, you want me to hike up my fucking skirt? What the fuck is your problem? I’m not going anywhere, you’re just some roided out freak with a fucking clipboard. And your stupid little fucking rope! You know what, you may have power now but you are not god. You’re a doorman, okay. You’re a doorman, doorman, doorman, doorman, doorman, so… Fuck You! You fucking fag with your fucking little faggy gloves.

Doorman (Craig Robinson): I know… you’re right. I’m so sorry, I fuckin’ hate this job. I don’t want to be the one to pass judgment, decide who gets in. Shit makes me sick to my stomach. I get the runs from the stress. It’s not cause you’re not hot, I would love to tap that ass. I would tear that ass up. I can’t let you in cause you’re old as fuck. For this club, you know, not for the earth.

Debbie: What?

Doorman: You old, she pregnant. Can’t have a bunch of old pregnant bitches running around. That’s crazy. I’m only allowed to let in five percent black people. He said that, that means if there’s 25 people here I get to let in one and a quarter black people. So I gotta hope there’s a black midget in the crowd.Note: thank you to the poster on IMDB.com who transcribed this wonderful exchange from Knocked Up so I didn’t have to.

I would love to hear your thoughts on your favorite moments from these films or about any glaring omissions.

Laughing at PRECIOUS?

Writing about a movie like Precious (2009, Lee Daniels) is fraught with difficulties and opportunities for saying the wrong thing. As a social problem film, based on Sapphire’s novel Push, Precious attempts to illuminate, with as much visceral charge as possible, the struggles of one African American teenager to escape soul crushing poverty. The film thrusts its “reality” in the viewer’s face like a dare, effectively asking us “Can you watch this? Can you stomach this?”

For example, early in the film we see Precious (Gabourey Sidibe) washing dishes in the dim, depressing kitchen of the New York City apartment she shares with her somewhat one-dimensionally villainous mother, Mary (Mo’Nique). In the background of the frame Mary barks questions at her daughter, the glow of the television screen reflected on her angry face. But we remain in the foreground of the shot, with Precious, as she measures her words, almost swallowing them, knowing that any response she offers will be the wrong one. Suddenly, violence explodes the frame as Mary hurls a heavy object at her daughter’s head, knocking her to the ground. It a shocking moment that immediately cuts to a flashback of Precious being raped by her father. The filmmaker clearly wants to place the viewer in Precious’ point of view: we hear the sickening, rhythmic pulse of the creaking mattress, the crying of a baby (the product of previous sexual abuses), and the grunting of her father, who whispers to his daughter as he defiles her. It is a truly horrifying scene.

When life becomes too intense for Precious, as it does in this scene, she imagines herself in fantasy worlds where she is a glamorous star, and thankfully, the viewer gets to go along with her (who would want to stay in that rape scene?). It is a testament to Sidibe’s acting skills that she is able to create such a vivid distinction between the woman she is in her fantasies and the woman she is in real life; one persona beams, struts and asks you to look and admire, while the other shrinks inward and demands that you look away.

Although Precious swerves perilously close to the “poverty porn” found in last year’s critical darling, Slumdog Millionaire (2008, Danny Boyle), I think it was able to avoid most of the pitfalls of its “children in peril” predecessor. While Slumdog seemed to revel in its moments of high tragedy — the blinding of a young boy with hot acid, the violent raiding of a slum village, the prostitution of little girls — Precious exposes us to the horrors of its protagonist’s life but only in small bursts. Furthermore, the message of Slumdog seemed to be that “Poverty sucks but it will prepare you to later win a lot money in a game show, to be followed by a really fun Bollywood number in a train station with the woman of your dreams, so don’t feel too bad about it. ” Or maybe I just misread the film?

By contrast, Precious had a more ambiguous ending. After (rightfully) refusing to allow her mother back into her life (a scene that generated a round of applause at my screening), we see Precious emerge on the streets of New York, with her two children. Precious is still poor, still only reading at an 8th grade level, still the product of (double) incest, still HIV positive, still a single mother, but she is smiling. And the non-diegetic music sounds almost triumphant. But this is no choreographed Bollywood number. The audience does not exit the theater feeling “Phew! I’m glad it all worked out in the end.” Rather, as the credits rolled I felt that I had heard one woman’s story, that this story was still unfolding somewhere, and that she still had much to do.

Thus, I was relieved to find that Precious was not nearly as exploitative as I thought it would be (though many critics disagree), but this does not sum up my experience of the film. While I sat in my chair, horrified and saddened by the images on the screen, something very different was happening in that sold out movie theater. People were laughing. A lot.

For example, one of the film’s most (at least for me) emotionally powerful scenes is where Mary (Mo’Nique) finally admits to her culpability in the repeated raping of her daughter (and yes, Mo’Nique truly deserves all the buzz she has been getting for this role). I don’t think we are intended to empathize with Mary in this scene, but we do gain some insight into how her home became a nightmare of rape and anger and jealousy. It is difficult for Mary to vocalize these horrible things and the weight of this confession causes her to blubber and sputter. I cried during this scene but most of the people in the theater were laughing. It was a curious moment for me because I wondered if these people were just hard-hearted cynics or if maybe I was just a sap.

When I got home that night I began to search online to see if this phenomenon had happened anywhere else and was surprised to see that it had (go here, here and here ). So what to make of this laughter? I have a few ideas:

1. The Mo’Nique Factor

As I mentioned, Mo’Nique was really wonderful and convincing in this role. But, as we all know, Mo’Nique is first and foremost a comedienne. And fans of her work, who would be lured to the film, curious to see this actress in a new role, possibly found it difficult to take her seriously.

2. People were Uncomfortable

It is awkward to watch images of rape and child abuse in any setting, but in a crowded theater it becomes even more awkward. And given that Precious was punctuated with fantasy images and moments of genuine comic relief, I think laughter may have been a natural response during those moments of stunned silence, when the images onscreen were simply too horrifying to process.

3. The Tyler Perry Factor

Precious is not a Tyler Perry film, but he did co-produce it (along with Oprah Winfrey) and his name was linked with the film in the media blitz leading up to its release ( also here and here). Other Perry-directed films, like The Family that Preys (2009) and Madea’s Family Reunion (2002), mix broad comedy with moments of real tragedy. Therefore, any audience members drawn into the theaters based on Tyler’s brand name may have been expecting to laugh.

4. It Really Is Poverty Porn

Initially I was a bit disturbed by the audience’s response to this film. How could they laugh at such tragedy? But after mulling it over for a few days I started wonder if maybe I was the one who was responding inappropriately to Precious. Maybe this audience, which was 70% African American, was laughing, not at the tragedy of Precious’ life, but at the audacity of Hollywood and its attempts, once again, to make African American life into a horror show. Armond White, whose scathing review has been quoted all over the internet, writes that:

Precious raises ghosts of ethnic fear and exoticism just like Birth of a Nation. Precious and her mother (Mo’Nique) share a Harlem hovel so stereotypical it could be a Klansman’s fantasy. It also suggests an outsider’s romantic view of the political wretchedness and despair associated with the blues. Critics willingly infer there’s black life essence in Precious’ anti-life tale. And the same high-dudgeon tsk-tsking of Hurricane Katrina commentators is also apparent in the movie’s praise. Pundits who bemoan the awful conditions that have not improved for America’s unfortunate are reminded that they are still on top.

While I think White engages in a bit of a hyperbole in his review (Little Man [2006, Keenan Ivory Wayans] is a better film? Really?), he does make a good point: does Precious merely assuage liberal guilt over the persistance of the profound class and racial divides in this country by allowing the haves to weep over the fates of the have-nots? Perhaps the laughter of those around me was a way of rejecting or resisting this Hollywood offering, of refusing to cry over images that are calculated to make us do just that?

So to sum up this contradictory post: my experience of Precious left me feeling confused (and even ashamed) about my relationship with the film image and about the role that film can and should play in the depiction of social problems. Can a film about a suffering individual ever avoid being conflated with an entire social group? Can these films ever not be poverty porn? What is the value in putting these images on the big screen?

I would love to hear your thoughts about this film and your experiences watching it the theaters.

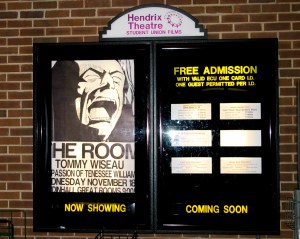

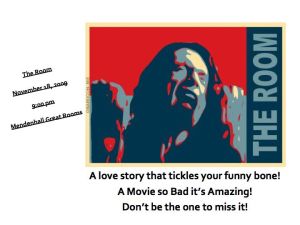

Screening Tommy Wiseau’s THE ROOM

As discussed in previous posts, I am teaching “Topics in Film Aesthetics” this semester, with a focus on what is known as “trash cinema.” For those unfamiliar with this term, trash cinema refers to films thathave been relegated to the borders of the mainstream because of their small budgets, inept style, offensive subject matter, and/or shocking political perspectives. All semester long my students have watched marginalized films like The Sex Perils of Paulette (1965, Doris Wishman) and Sins of the Fleshapoids (1965, Mike Kuchar), interrogating and debating their style, subject matter, and ideology. Why are these films considered to be “bad” movies and what do we have to gain by studying them?

We also spent much of the semester discussing how and why certain films (The Rocky Horror Picture Show [1975, Jim Sharman], El Topo [1970, Alejandro Jodorowsky]) were able to achieve cult status as midnight movies and what drives audiences to perform elaborate rituals at film screenings. In keeping with these discussions, the class project was to host, promote and run a screening of a contemporary cult film, the notoriously awful The Room (2003, Tommy Wiseau). Since my students had read so much about midnight movies and the great lengths that theater exhibitors would go to draw in potential ticket buyers (known as “ballyhoo”), my hope was that the class would put some of those lessons into practice.

Early in the semester the class broke themselves up into working groups: promotions, advertising, booking the venue, etc. The advertising group was responsible for designing flyers, posters and ad copy for the promotions group to implement. Although money is tight in my department, my chair was kind enough to allow us limitless copies for our flyers and $50 for two large posters (I limited my role in this project to obtaining funds for the $100 screening license and for adveritising materials):

Once posters and flyers were created, it was time for the promotions group to start spreading the word. In addition to putting flyers up around campus and doing a word of mouth campaign, they started up a Facebook group for the event and convinced a writer for the campus newspaper, The East Carolinian, to mention the screening in an article about campus happenings.

Nevertheless, as the night of the screening approached I was a little nervous: I had not seen many flyers up around campus and I was beginning to doubt the class’ enthusiasm for the project. To make matters worse, the screening was held on a rainy night (ECU students are relcutant to do anything unless it’s 70 degrees outside and precipitation free) when District 9 (2009, Neill Blomkamp) was playing for free in the same building as part of the Student Activities Board’s fall film series. Finally, our event was booked in a difficult to locate area of the student union. It therefore made sense when barely 50 seats were taken 10 minutes before the start of the event.

I could tell that my students were also starting to get nervous — part of their grade would be based on how many people they could entice into the theater (after all, a theater exhibitor who couldn’t fill seats would lose his/her business). With a few minutes to spare, audience members began to appear in droves, wet from the rain but ready for a good time. By the time we started the film, we had at least 200 attendees:

Most of the people entering the theater took a bag of props to throw at the screen including: plastic spoons (whenever a framed picture of a spoon appears in the mise en scene), chocolates (during a supposed-to-be-erotic scene involving a box of chocolates), and footballs (several scenes feature the male characters tossing around a football, presumably because this is what Wiseau assumes American men do to bond with each other):

I told the students that in addition to gathering a large crowd they needed to foster a participatory screening environment. A silent audience was simply not acceptable. To encourage participation, audience members were handed a photocopied list of rituals selected by the class:

“SPOON!” – Nearly all the artwork in the film features spoons. When they appear in the shot, yell “Spoon!” and fling yours at the screen.

“DENNY!” – Used to herald the arrival/departure of the tragic kidult. “Hi & Bye” is encouraged.

“SHOOT HER!” – Yelled during Lisa’s couch conversation with her mother. The throbbing neck is the cue. Also acceptable, “QUAID, GET TO THE REACTOR!”

“BECAUSE YOU’RE A WOMAN!” – Useful after any comment made in regards to a female character. Considered a dig at the film’s casual misogyny.

“FOCUS! UNFOCUS!” – Frequent shots slip in and out of focus and it is customary to yell “FOCUS” when it gets blurry. Feel free to yell “UNFOCUS!” during the gratuitous sex scenes.

“FIANCE/FIANCEE” – This term is never uttered, instead Johnny or Lisa refer to one another as their future wife/husband. That is the cue to scream “Fiancé & Fiancée”

“ALCATRAZ” – Yell this during scenes framed with bars & during establishing shots of the famous island prison. Also encouraged, “WELCOME TO THE ROCK!” (Connery-esque only)

“GO! GO! GO! GO!” – Used to cheer on tracking shots of the bridge. Celebrate when it makes it all the way across, voice your disappointment when it doesn’t.

“EVERYWHERE YOU LOOK” (Full House theme) – Sung during establishing shot of the San Francisco homes that look eerily similar.

“MISSION IMPOSSIBLE THEME” – Hummed during the phone tapping scene.

“WHO THE FUCK ARE YOU!” – Yelled when characters appear on screen that are out of place or unknown. (Happens more than you think)

“YOU’RE TEARING ME APART, LISA!” – Johnny channels his inner James Dean near the conclusion of the film. Yell along, louder the better.

While this is only a small list of ways to get involved, feel free to interject your own thoughts throughout the screening or join in with audience members who aren’t seeing the film for the first time. All we ask is for you to be safe and respect those around you. Enjoy!

The evening also opened with a brief introduction to the film and its colorful production history. Our Master of Ceremonies encouraged the audience to participate and demonstrated a few of the rituals for the audience.

These tactics seemed to work because almost as soon as the film began, with its useless, extended establishing shots of San Francisco, the crowd was yelling at the screen. They followed the suggested rituals (with “Because you’re a woman!” and “Denny!” being two crowd favorites) but also lots of ad-libbing.

Note: Not from our screening.

When, for example, Lisa (Juliette Danielle) mixes Johnny (Tommy Wiseau) a cocktail of what appears to be 1/2 scotch and 1/2 vodka, someone behind me declared “I call it…scotchka!” [note: I just discovered that this particular line is already a Room ritual]. And whenever a character commented on how “beautiful” Lisa was, several audience members would yell “LIAR!” In fact, the room was rarely silent; people booed, groaned, clapped and heckled throughout the screening.

Note: Not from our screening.

I was hoping that the students would have come up with some more inventive advertising tactics, especially given the time we spent discussing how classical exploitation films like Mom and Dad (1945, William Beaudine) were advertised and promoted. Ultimately though, the class screening of The Room lived up to my expectations. The crowd was rowdy and interactive and everyone seemed to have a great time. Most importantly, I think my students had a great opportunity to experience firsthand what they had only been able to read about.

How GLEE Taught my Students to Stop Worrying and Love the Musical

This week in Introduction to Film was musical week — my favorite week. I adore musicals because they are designed to be loved. As Jane Feuer has argued, musicals, particularly the backstage musicals released by MGM’s Freed Unit, function to affirm the necessity of the musical genre in the lives of its audience (458). Forever striving to recreate the sense of liveness lost when the musical left the Broadway stage and became a mass-produced product, classical Hollywood musicals wish to break down the barriers between the performer on screen and the audience sitting in the theater. These films want to merge the dream world of song and dance with the mundane real world where we trip over our feet. Musicals achieve this goal by making song and dance appear natural, effortless and integrated into every day life.

My Intro to Film students are generally put off by musicals, finding their song and dance numbers to be “awkward” or “cheesy” (their words, not mine). And so I usually devote lecture time to explaining how many musicals attempt to integrate song and dance naturally into the diegesis — to ease this transition for the viewer. We look, for example, at one of my all time favorite musical numbers, “Someone At Last” from A Star is Born (1954).

Aside from the crude ethnic stereotyping, I find this number to be completely enchanting every time I watch it. I point out Garland’s skillful use of bricolage, that is the way she “happens” to find certain props around her living room — a smoking cigarette, a tiger skin rug, a table resembling a harp — at just the moment that she needs them. The “mundane world” of the living room becomes, through the joy of performance, a Hollywood set (which, in reality, it is). Bricolage creates a feeling of spontaneity, which is central to the appeal of the musical. As Feuer argues “The musical, technically the most complex type of film produced in Hollywood, paradoxically has always been the genre that attempts to give the greatest illusion of spontaneity and effortlessness” (463). The more natural a performance appears, the more we enjoy it. As we watch this routine we momentarily forget that Vicki Lester/Judy Garland is the most famous female musical star and (both within and outside A Star is Born) and is instead a devoted wife who loves to sing and dance for her husband (James Mason) and for us.

When I show this scene I usually have to put on quite a show myself, explaining to my students exactly why this performance is so satisfying, so joyous. But this week when I showed this clip I heard my students giggling (appropriately) at Judy’s jokes and expressing amusement at her clever use of props. They were enjoying it. The same thing happened when I showed them another one of my favorites, the iconic title number from Singin’ in the Rain (1952). In this scene, Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) has just shared a kiss with Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), and is consequently filled with joie de vivre. It is pouring rain outside but he dismisses the car that waits to drive him home. Don wants to walk and luxuriate in this moment of romantic bliss. Then, he just can’t help himself. His steps down the sidewalk turn almost involuntarily into dance and his dreamy, romantic thoughts become song. Here dancing and singing truly emerge out of a “joyous and responsive attitude toward life” (459).

As this scene played on the big screen I turned to look at my 100 students and was delighted to see the enchanted looks on their faces. They were enthralled, as I am every time I watch this number. They were enjoying themselves. At last!

But why? Why now? The answer is Glee. When I began my lecture on the musical earlier this week I told my students that by the end of the week I was hoping to have some musical converts in the class. “If you are watching the show Glee right now” I said, “the convention of breaking into song and dance shouldn’t be that foreign to you.” A large portion of the class nodded their heads in reponse to this. As it turned out, more than half of the students in my class are watching the show. And I think this has made all the difference.

Though I have not always been happy with the politics of Glee, I have always been satisfied with their adoption of the conventions of the backstage musical. Characters sing when they are in love (“I Could Have Danced All Night”) or lust (“Sweet Caroline”) and they sing when their hearts are breaking (“Bust The Windows”). And the most successful (i.e., the most passionate) group performances in the series arise, as they do in the classical Hollywood musical, when the show’s characters are working together and cooperating (“Don’t Stop Believin’,”Keep Holding On”). Resolution in the narrative equals resolution on the stage. The classical Hollywood musical incarnate.

So while Glee may not be breaking any new ground in its use and depiction of homosexual characters or ethnic minorities, it has, to my delight, given my students license to love the musical and to revel in its joy. And that’s something to be gleeful about.

Works Cited

Feuer, Jane. “The Self Reflexive Musical and the Myth of Entertainment.” Film Genre Reader III. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003. 457-471.

- ← Previous

- 1

- …

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Next →