BET’s BALDWIN HILLS: Injecting Race and Class into the Projective Drama

For those of you who are regular readers of this blog (hi Mom!), you may have noticed that my posting has dropped somewhat over the last few weeks. This is due to the mid-semester crunch as well as some other writing deadlines I had to meet.

One of these deadlines was for the wonderful site Flow TV, “a critical forum on television and media culture published by the Department of Radio, Television, and Film at the University of Texas at Austin. Flow’s mission is to provide a space where the public can discuss the changing landscape of contemporary media.”

If you’d like to read my article on BET’s reality show, Baldwin Hills, it went live today and can be accessed through the link below:

BET’s Baldwin Hills: Injecting Race and Class into the Projective Drama

MAD MEN FINALE Recap

I was not able to watch the Mad Men finale on Sunday night because I was simply too tired to stay awake for it. The problem with writing a Mad Men finale recap late is that you might as well not write it at all. By now all of the die hard Mad Men fans have already gorged themselves on recaps and reviews of “Shut the Door. Have a Seat.” And after reading some particularly insightful pieces ( for example James Poniewozik’s review on Time.com), I wonder how much I have to add.

But the thing about Mad Men is that it almost begs you to write about it. So gorged or not my friends, I hope you have some room for dessert:

1. The Divorce

If any TV couple should get a divorce, it’s Don and Betty Draper. In addition to lying to his wife for the last ten years about his family, his past and his real name, Don has systemically cheated on his wife. “Cheat” doesn’t even really encompass Don’s behavior over the last 3 seasons — he has pursued extramarital affairs with a persistency and zeal unmatched by even Three’s Company‘s Larry Dallas.

And while Betty’s transgressions were less severe, she did have sex with a stranger in a bar bathroom and nurtured an emotional relationship with Henry Francis (who I do not trust AT ALL). As Don chides, “All along you’ve been building a life raft.” Oh Betty.

Don and Betty should break up and yet, watching them go through the various motions of the TV couple divorce — meeting with a lawyer, having “the talk” with their children — I couldn’t help but feel very sad. Indeed, when Don crawled into bed with Sally, who slept in Grandpa Gene’s old pull out cot to be closer to her exiled Daddy (even though, as she states, “Gene’s room is creepy”), I was overwhelmed with emotion. There was hardly room for the two of them in that creaky little bed, but in he crawled, still wearing his suit. Don’s children seem to be his only link to his emotions — to the real person (is he called “Dick Whitman”?) under the Don Draper veneer — and so I see this divorce primarily as Don’s loss, rather than Betty’s. Though my guess is that Season 4 will reveal the toll that divorce is taking on Betty.

2. Joan!

I love Joan. Who doesn’t love Joan? And the moment that Don, Roger Sterling, Bert Cooper and Lane Pryce began to plot how they might abscond from Sterling Cooper with their accounts and files in tact I turned to my husband and said “Joan! They’re going to get Joan!” And when Joan returned she was once again wearing her iconic pen around her neck — a symbol of her power and independence that had been absent from her ample bosom for most of the season. Welcome back pen and welcome back Joan!

3. Peggy

I imagine that if you tried to hug Peggy Olsen she would be one of those people who stiffen and then pat you uncomfortably on the back. Peggy is not sentimental but, paradoxically, she is a successful copywriter because she understands sentiment all too well. Don even tells Peggy — in an attempt to woo her into joining his new firm — that she alone understands that “something terrible has happened” (which I took to mean “Peggy, you understand that people are fundamentally sad and you know how to exploit that sadness in order to sell them consumer goods”).

In this episode Peggy finally seemed to recognize her own worth as a copywriter and as an asset to Don. She initially tells Don to shove it when he tries to strong-arm her into leaving Sterling Cooper, making it clear that she is not like the other women in Don’s life. If he wants her, he’ll need to spill his guts. And when he shows up at her apartment, hat in hand, Peggy weeps. Sure, they were discussing work, but they were also discussing their complicated relationship. When Peggy asks Don if he will stop speaking to her if she refuses his offer, he counters, “No. I will spend the rest of my life trying to hire you.” “Damn that Don Draper’s smooth!” was my husband’s reply to this. But I think Don was being sincere. Peggy is more than just a great copywriter to Don — they are each other’s double and Don finally admits that out loud in this episode. I hope their relationship is explored more in Season 4.

4. The Lighting

With its superb cast, nuanced writing and slow burn narratives, it is easy to overlook Mad Men‘s understated formal style. This season — and especially in this finale — I have been captivated by the show’s Rembrandt lighting. For example, after Roger and Don convince Pete Campbell to leave Sterling Cooper they head to a bar to commiserate and plot their next move. The set is soaked in shadows, with pockets of brightness here and there. This lighting style is reminiscent of The Sopranos, which also used chiaroscuro lighting to depict a homosocial milieu. In this mix of light and darkness men discuss the things that (they think) they need to keep from their women: their sexual dalliances, their (dirty) business, their feelings.

This is also the lighting that is frequently used in the flashback sequences to Don’s childhood. In the finale Don’s father is killed in the darkness of the stables, with father and son alone in the shadows.

5. The Music

Many recaps have already compared this finale to a heist movie (also here and here), with Don, Roger and Bert assembling a team of the Sterling Cooper’s finest in order to steal the dying company’s riches. Roger was firing off zingers like George Clooney and everyone looked like they were having a grand old time. This mood was enhanced by the jaunty music used throughout the episode. Is it my imagination or does this series rarely employ non-diegetic music during an episode (saving it instead for the finale scene/closing credits)? I found myself really noticing the music during these scenes, as if the show was winking at us, letting us know that this heist storyline was all campy fun. This music noticably disappears in the scenes with Betty and in Don’s flashbacks to his childhood, which are highly tragic.

Overall I found the Season 3 finale to be immensely satisfying — the perfect cap to a wonderful, nuanced, slow burn (NOT SLOW!) season. I can’t to see what Season 4 holds in store…

How GLEE Taught my Students to Stop Worrying and Love the Musical

This week in Introduction to Film was musical week — my favorite week. I adore musicals because they are designed to be loved. As Jane Feuer has argued, musicals, particularly the backstage musicals released by MGM’s Freed Unit, function to affirm the necessity of the musical genre in the lives of its audience (458). Forever striving to recreate the sense of liveness lost when the musical left the Broadway stage and became a mass-produced product, classical Hollywood musicals wish to break down the barriers between the performer on screen and the audience sitting in the theater. These films want to merge the dream world of song and dance with the mundane real world where we trip over our feet. Musicals achieve this goal by making song and dance appear natural, effortless and integrated into every day life.

My Intro to Film students are generally put off by musicals, finding their song and dance numbers to be “awkward” or “cheesy” (their words, not mine). And so I usually devote lecture time to explaining how many musicals attempt to integrate song and dance naturally into the diegesis — to ease this transition for the viewer. We look, for example, at one of my all time favorite musical numbers, “Someone At Last” from A Star is Born (1954).

Aside from the crude ethnic stereotyping, I find this number to be completely enchanting every time I watch it. I point out Garland’s skillful use of bricolage, that is the way she “happens” to find certain props around her living room — a smoking cigarette, a tiger skin rug, a table resembling a harp — at just the moment that she needs them. The “mundane world” of the living room becomes, through the joy of performance, a Hollywood set (which, in reality, it is). Bricolage creates a feeling of spontaneity, which is central to the appeal of the musical. As Feuer argues “The musical, technically the most complex type of film produced in Hollywood, paradoxically has always been the genre that attempts to give the greatest illusion of spontaneity and effortlessness” (463). The more natural a performance appears, the more we enjoy it. As we watch this routine we momentarily forget that Vicki Lester/Judy Garland is the most famous female musical star and (both within and outside A Star is Born) and is instead a devoted wife who loves to sing and dance for her husband (James Mason) and for us.

When I show this scene I usually have to put on quite a show myself, explaining to my students exactly why this performance is so satisfying, so joyous. But this week when I showed this clip I heard my students giggling (appropriately) at Judy’s jokes and expressing amusement at her clever use of props. They were enjoying it. The same thing happened when I showed them another one of my favorites, the iconic title number from Singin’ in the Rain (1952). In this scene, Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) has just shared a kiss with Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), and is consequently filled with joie de vivre. It is pouring rain outside but he dismisses the car that waits to drive him home. Don wants to walk and luxuriate in this moment of romantic bliss. Then, he just can’t help himself. His steps down the sidewalk turn almost involuntarily into dance and his dreamy, romantic thoughts become song. Here dancing and singing truly emerge out of a “joyous and responsive attitude toward life” (459).

As this scene played on the big screen I turned to look at my 100 students and was delighted to see the enchanted looks on their faces. They were enthralled, as I am every time I watch this number. They were enjoying themselves. At last!

But why? Why now? The answer is Glee. When I began my lecture on the musical earlier this week I told my students that by the end of the week I was hoping to have some musical converts in the class. “If you are watching the show Glee right now” I said, “the convention of breaking into song and dance shouldn’t be that foreign to you.” A large portion of the class nodded their heads in reponse to this. As it turned out, more than half of the students in my class are watching the show. And I think this has made all the difference.

Though I have not always been happy with the politics of Glee, I have always been satisfied with their adoption of the conventions of the backstage musical. Characters sing when they are in love (“I Could Have Danced All Night”) or lust (“Sweet Caroline”) and they sing when their hearts are breaking (“Bust The Windows”). And the most successful (i.e., the most passionate) group performances in the series arise, as they do in the classical Hollywood musical, when the show’s characters are working together and cooperating (“Don’t Stop Believin’,”Keep Holding On”). Resolution in the narrative equals resolution on the stage. The classical Hollywood musical incarnate.

So while Glee may not be breaking any new ground in its use and depiction of homosexual characters or ethnic minorities, it has, to my delight, given my students license to love the musical and to revel in its joy. And that’s something to be gleeful about.

Works Cited

Feuer, Jane. “The Self Reflexive Musical and the Myth of Entertainment.” Film Genre Reader III. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003. 457-471.

Ironic Muppets and Horny Houseplants: SESAME STREET’s Dual Address

This week I was two-timing my blog by posting on another, far more critically incisive site, In Media Res. If you are not familiar with this site, here is its basic mission:

In Media Res is dedicated to experimenting with collaborative, multi-modal forms of online scholarship.

Each day, a different scholar will curate a 30-second to 3-minute video clip/visual image slideshow accompanied by a 300-350-word impressionistic response.

We use the title “curator” because, like a curator in a museum, you are repurposing a media object that already exists and providing context through your commentary, which frames the object in a particular way.

The clip/comment combination are intended to both introduce the curator’s work to the larger community of scholars (as well as non-academics who frequent the site) and, hopefully, encourage feedback/discussion from that community.

Theme weeks are designed to generate a networked conversation between curators. All the posts for that week will thematically overlap and the participating curators each agree to comment on one another’s work.

Our goal is to promote an online dialogue amongst scholars and the public about contemporary approaches to studying media.

In Media Res provides a forum for more immediate critical engagement with media at a pace closer to how we typically experience mediated texts.

This week’s theme is “Kids TV” and several wonderful scholars are curating clips including: Michael Z. Newman (on The Wizards of Waverly Place), Heather Hendershot (on Ernie and Bert slash), Elana Levine (on Aaron Stone), and Jason Mittell (on Yo Gabba Gabba). My clip and curator’s note, entitled “Ironic Muppets and Horny Houseplants: Sesame Street‘s Dual Address” can be found here.

I hope you’ll check it out and possibly join the conversation!

WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE review

My husband does not like to go out to the movies. But after viewing the trailer for Where the Wild Things Are a few weeks ago he changed his mind. “That,” he told me, “I would see in the theater. We can bring the 3-year-old.” Here my heart sank: I was ecstatic that my husband was willing to venture out of the house for a movie. But after looking into the film’s production history and reading early reviews, I knew that this film was not for 3-year-olds.

Seeing the film this past weekend only confirmed my hunch. It’s not that Spike Jonze’s vision of Maurice Sendak’s classic 1963 book is too violent for children (though there are scenes in which lives are threatened and limbs are removed). Rather, the problem is that the movie is simply not for children. Case in point: when I went to see the film a girl about the age of 7 or 8 was seated in front of me and she continually asked her parents questions like “Why was that funny? What happened? Why did you guys take me to a 9:30 pm movie?” Okay, that last question was mine.

This child was frustrated and my guess is that the film will also frustrate audience members who were hoping to share the movie with their children, much as they shared the beloved book with them. But, I for one am completely satisfied with Jonze’s re-visioning of Sendak’s work. I’m glad it’s not for kids.

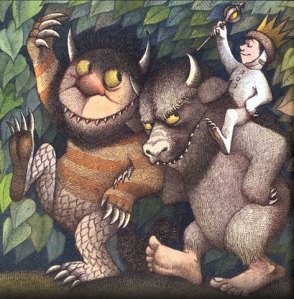

Sendak's Max starts the wild rumpus. While Jonze took many liberties with his adaptation, the original story remains in tact. A little boy is punished for being a “wild thing!” and escapes to a world in which being a wild thing is celebrated. After indulging his id for a while the boy decides to return to the place where “someone loved him best of all.”

Jonze's Max rumpusing with Carol. Jonze’s film completely immerses us in the consciousness of a 9-year-old boy (Max Records): we listen as he composes imaginative stories for his mother while idly poking at the pantyhose on her toes and we experience how a child’s emotions can change in an instant from pure joy to pure pain during a raucous snowball fight. And this is just in the first 15 minutes of the movie.

Max surveys his kingdom. Once Max reaches the land of the wild things he is made king of all wild things and his first post-election promise is to “keep out all the sadness.” How does he does he achieve this impossible task? By initiating a “wild rumpus” through the woods, drafting plans for an elaborate fort — a place “where only the things you want to happen, would happen” — and by promising the beasts that every night they will sleep in a “real pile” (that is, in a giant snoring heap of wild things). Of course, Max soon learns that it is impossible to keep all of the wild things happy all of the time. Carol (James Gandolfini) is perpetually jealous, Judith (Catherine O’Hara) gives him way too much lip, and KW (Lauren Ambrose) insists on making friends (or are they captives?) outside of her small social circle. In other words, Max learns that he much prefers being a child. Let the adults worry about keeping everyone happy. Amen, Max.

For me, the emotional high point of the film was when Max boarded his boat to go home (a trip that lasts “night and day and in and out of weeks and almost over a year”). The wild things gather on the shore to say good-bye, looking forlorn and abandoned, as children do when a loved one departs. KW approaches Max, putting her face against his, and tells him, “Please don’t go. I’ll eat you up, I love you so.” That was always my favorite line of the book because it could easily come out of the mouth of a child or a parent. I often tell my daughter, when she is being particularly lovable, that I could “eat her up.” For me this is a gesture of love, but for her this is a frightening concept: to be consumed by the love of another. “Don’t eat me up!” she cries and then I have to assure her that I am only joking. But I’m not, really. I could eat her up. Along the same lines, when my daughter was younger she would occasionally bite me when giving me a big hug. Even children understand that love is the overwhelming desire to consume the beloved.

A columnist for Entertainment Weekly, Christine Spines, took her 5-year-old and 15-year-old sons to see the film and wrote about her experiences. Apparently, the 5-year-old “loved” it. But I still see this as a movie for adults, not for kids. Kids don’t need to see Where the Wild Things Are because they are living Max’s life right now. Children know well what it is to run and jump with no purpose other than the joy of running of jumping. Children are capable of imagining entire worlds for themselves in which they are the king. And children understand that adults have a responsibility to take care of them and to love them, even when they are acting most like a wild thing. Adults, on the other hand, need to be reminded of these departed joys. This movie filled me with both longing and happiness. This movie is not for my daughter. This movie is for me. Thanks Spike.

BORED TO DEATH: Why It’s My Favorite New Show

I first started watching Bored to Death because I was desperate to fill the “quirky film noir” void in my TV diet since Veronica Mars went off the air in 2007. And the pilot episode seemed to be headed in that vein: we meet a frustrated novelist named Jonathan Ames (Jason Schwartzman) just as his girlfriend, Suzanne (Olivia Thirlby), is moving out. She is tired of his drinking, his pot smoking and his overall immaturity. Jonathan confirms Suzanne’s decision when they meet for coffee in a later episode and he is only able to articulate why he misses her in terms of concrete material needs: “I’m living like an animal. I have no toilet paper, no food, no toothpaste.”

Jonathan’s solution to his heartache and his writer’s block (he cannot write his second novel) is to moonlight as a private detective (he gets the idea after reading some Raymond Chandler). What follows is a series of anti-noir cliches. As Jonathan stakes out his first case we see him standing in the rain in the moonlight, his childish bowlcut dripping onto his khaki trench coat. When he goes to a bar to pump the bartender for information he orders a whisky and promptly chokes on it. “I’m on a white wine regimine,” he explains. And he ends up spending more money on bribing people for information than he makes on his first case. No, Jonanthan is not Sam Spade.

However, after the pilot the series shifted genres. It became less about noir and more about Jonathan and his best friends Ray (Zach Galifianakis), a whiny, infantile comic book artist, and George (Ted Danson), the equally whiny and infantile editor-in-chief of an unnamed New York magazine. In HBO shows about male friendship, like Entourage, there is a clear alpha male (Vincent Chase) and a clear buffoon (Johnny Drama) but no so here. The three male leads in Bored to Death are each buffoonish in their own way. And although Jonathan’s neurotic Jewish character invites comparisons to Curb Your Enthusiasm’s Larry David, or even further back, to Woody Allen in Manhattan (1979) or Annie Hall (1977), he is somehow more…likeable. Yes he is selfish and self absorbed but it is also clear that he is kind and even moral. After Ray is bullied into getting a colonic and must endure a long subway ride home, Jonathan seems genuinely concerned, offering to massage his friend’s shoulders. Sure, he’s stoned at the time, but he cares…about his friend’s colon.

As for the women in the series, well, the women aren’t all that important. Or maybe it’s that they’re too important? Jonathan pines for his ex-girlfriend Suzanne, Ray is nagged by current girlfriend Leah (Heather Burns), and George moves from one young conquest to the next (his current fetish is armpit hair). For these men women provide pain, torment and delight, but ultimately these men seek out the company of other men. This is certainly a recipe for misogyny and for stereotyped female characters, but this doesn’t happen in Bored to Death. Rather, women are a force to be reckoned with: they are inscrutable, independent and appear to function perfectly well without men (except when they need to borrow some sperm). There’s a running joke in the series in which Jonathan and Ray find themselves tripping over trendy baby strollers whenever they want to kvetch together in their favorite coffee shop. By the time they reach their thirties, many men have started families, so for Jonathan and Ray these strollers are a threat, a mystery, a symbol of the responsibility they cannot take on. Indeed, Ray complains that Leah’s children have no respect for him. “They call me fat. And hairy,” he complains. And he is. In this show the men are the problem, not the women.

So far the reviews for this new show have been tepid. The word “precious” and “self indulgent” have been bandied about. But I don’t see Bored to Death as a Curb-derivative or as a “low-stakes version of Woody Allen’s Manhattan Murder Mystery“. Larry David and Woody Allen are so eccentric, so enveloped in their own worlds, that I find them difficult to relate to (and isn’t that part of their appeal?). Here’s the thing: I do find Jonathan relatable. As one of those “responsible adults” with the baby stroller in the coffee shop I understand and empathize with Jonathan. He’d like to be like me: write his novel, help his ex-girlfriend shop for toilet paper and stop smoking so much pot. But, sometimes I’d like to be like him: to play at being a private detective and have a glass of white wine while standing in the rain in my khaki trench coat.

So am I the only one who loves this show? Share your thoughts below.

THE BERMUDA DEPTHS: One Cinephile’s Movie Memories Finally Reach the Surface

Randall Martoccia has graciously agreed to write the first guest post ever for Judgmental Observer. Having a guest writer makes me feel important, like I’m too busy to write for my own blog. So while my servant boys feed me grapes and massage my feet please enjoy this guest post:

Thanks to Amanda for letting me guest write. I’m sure the rest of you will appreciate the break from the usual insight on this web site. Intelligent ideas can be so daunting.

This tale begins in the late 1970s. I was 7 years old, scared of girls, and infatuated with sea creatures. My parents, either through a desire to encourage my passion or due to negligence, let me see any marine-related movie, even though these tended to be thrillers. They took me to Jaws (1975, Steven Spielberg) (when I was 6-freakin’-years old), and then to Orca (1977, Michael Anderson) and Tentacles (1977, Ovidio G. Assonitis).

When I was 8 years old, my parents let my brother and me stay up late to watch another one of these creature features that followed in Jaws’s wake. This one was a network TV movie. A scene in which the turtle rises up and swamps a boat is pretty much all I remembered—and all that are left of that scene are fragments: A boat in rough seas. An ominous sky. A seven-story-tall, pissed off turtle.

Over the ensuing three decades, the patchy memory of the turtle kept coming back to me, but I had come to wonder if the scene was from a movie or a recurring dream. My memory never really nagged me so much for me to look into it. Any impulses to identify the movie were swept away by the usual business of life—or my lame version of it.

About two years ago, for one reason or another, I decided to find out for sure about this movie. Blessed be Google—it only took about ten minutes to find with the key words “giant sea turtle TV movie.”

It turns out the movie exists. It’s called The Bermuda Depths, directed by Tsugunobu Kotani and starring Connie Selleca and Carl Weathers. What is astonishing about the movie is the odd community that has formed around it. Here are some typical posts on the movie’s IMDB discussion board:

From yihaa2: Wow. I’m not crazy, it is a real movie, after 25 haunted years of dreams and fragmented memories, I really wasn’t imagining it.

From lilbearlovr: I had the same problem since I was a little kid. I was beginning to wonder if it was just some silly little kid dream.

From barbiegrrl: I have been telling people for years about the fragmented memories I had of seeing this movie as a kid, and no one ever knew what in the heck I was talking about!

From lamsaes: This is extraordinary. I thought I was the only one to remember this film. I saw it on TV when I was just a little kid. For a very long time, I thought I had imagined this film.

From traceymermaid: Holy smokes. Is this coincidence that so many of us are not only remembering this movie but are also taking action, such as writing on this message board? Maybe it is a symbol of something.

From Demarkov-1: My own experience with this movie is so similar to all of you…this is incredibly creepy and wonderfully comforting.

From newtondkc-1: Wow…so I’m not the only one in the world that remembers this flick…. I remember seeing this and I too was scared but strangely drawn to it. I remember the girl with the glowing eyes standing on a boat – I think she came out of the water? And the kids on the beach, carving their initials into the poor turtle’s shell – and then seeing the distorted initials on the back of the fully, fully grown giant turtle as well as a guy caught in the net that the turle was dragging into the depths.

Strangely enough, I have no memory of the oft-referenced girl with glowing eyes, but she would explain my fear of girls.

Michael Summers compares the Bermuda Depths phenomenon to the shared vision of Devil’s Tower in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977, Steven Spielberg), and I do wonder how many of you–like the skeptics in Close Encounters–are thinking that the authors of those posts and this blog entry are, well, nuts.

But I doubt all of you think this. While I was doing my sea-turtle research and reading The Bermuda Depths’ posts, my wife Christie (I got over my fear of women—or most of them) piped up and said that she had a similar experience with a different movie, making me think that this kind of experience was fairly common. I’m willing to bet that many of you—being movie junkies, scholars, or makers—have your own version of a giant sea turtle haunting you.

By the way, Christie’s fragmentary memory was of a short called “All Summer in a Day,” based on a Ray Bradbury story, which left her with little more than a image of the sweep of the sun’s ray under a closed door. But that image stayed with her for more than two decades.

Do you have your own haunting movie or television experience? An image fragment that you can’t shake? If you share them below, then perhaps I can help you to identify your movie or to discover a community of like-minded inviduals. Or, if you prefer, you can just call me “nuts.” With lilbearlvr, yihaa2, and barbiegrrl getting my back, I feel secure.

About the Author: When Randall Martoccia isn’t grading stacks of freshman papers he writes screenplays and makes short films. His “Pub of the Living Dead” and “They Shoot Zombies, Don’t They?” can be found on YouTube—though (alas) few people have found them. You can checkout his faculty profile here and you can e-mail him at: MARTOCCIAR@ecu.edu.